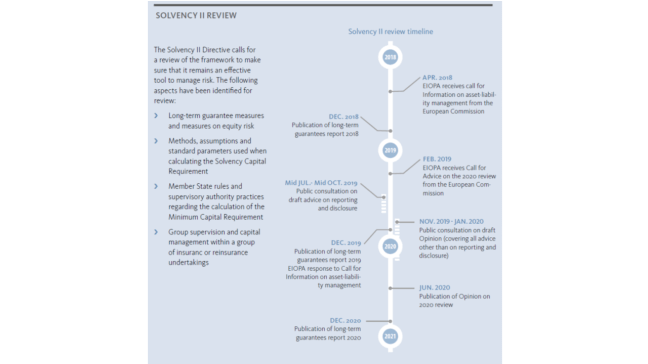

The Solvency II Directive provides that certain areas of the framework should be reviewed by the European Commission at the latest by 1 January 2021, namely:

- long-term guarantees measures and measures on equity risk,

- methods, assumptions and standard parameters used when calculating the Solvency Capital Requirement standard formula,

- Member States’ rules and supervisory authorities’ practices regarding the calculation of the Minimum Capital Requirement,

- group supervision and capital management within a group of insurance or reinsurance undertakings.

Against that background, the European Commission issued a request to EIOPA for technical advice on the review of the Solvency II Directive in February 2019 (call for advice – CfA). The CfA covers 19 topics. In addition to topics that fall under the four areas mentioned above, the following topics are included:

- transitional measures

- risk margin

- Capital Markets Union aspects

- macroprudential issues

- recovery and resolution

- insurance guarantee schemes

- freedom to provide services and freedom of establishment

- reporting and disclosure

- proportionality and thresholds

- best estimate

- own funds at solo level

EIOPA is requested to provide technical advice by 30 June 2020.

Executive summary

This consultation paper sets out technical advice for the review of Solvency II Directive. The advice is given in response to a call for advice from the European Commission. EIOPA will provide its final advice in June 2020. The call for advice comprises 19 separate topics. Broadly speaking, these can be divided into three parts.

- Firstly, the review of the long term guarantee measures. These measures were always foreseen as being reviewed in 2020, as specified in the Omnibus II Directive. A number of different options are being consulted on, notably on extrapolation and on the volatility adjustment.

- Secondly, the potential introduction of new regulatory tools in the Solvency II Directive, notably on macro-prudential issues, recovery and resolution, and insurance guarantee schemes. These new regulatory tools are considered thoroughly in the consultation.

- Thirdly, revisions to the existing Solvency II framework including in relation to

- freedom of services and establishment;

- reporting and disclosure;

- and the solvency capital requirement.

Given that the view of EIOPA is that overall the Solvency II framework is working well, the approach here has in general been one of evolution rather than revolution. The principal exceptions arise as a result either of supervisory experience, for example in relation to cross-border business; or of the wider economic context, in particular in relation to interest rate risk. The main specific considerations and proposals of this consultation paper are as follows:

- Considerations to choose a later starting point for the extrapolation of risk-free interest rates for the euro or to change the extrapolation method to take into account market information beyond the starting point.

- Considerations to change the calculation of the volatility adjustment to risk-free interest rates, in particular to address overshooting effects and to reflect the illiquidity of insurance liabilities.

- The proposal to increase the calibration of the interest rate risk submodule in line with empirical evidence. The proposal is consistent with the technical advice EIOPA provided on the Solvency Capital Requirement standard formula in 2018.

- The proposal to include macro-prudential tools in the Solvency II Directive.

- The proposal to establish a minimum harmonised and comprehensive recovery and resolution framework for insurance.

A background document to this consultation paper includes a qualitative assessment of the combined impact of all proposed changes. EIOPA will collect data in order to assess the quantitative combined impact and to take it into account in the decision on the proposals to be included in the advice. Beyond the changes on interest rate risk EIOPA aims in general for a balanced impact of the proposals.

The following paragraphs summarise the main content of the consulted advice per chapter.

Long-term guarantees measures and measures on equity risk

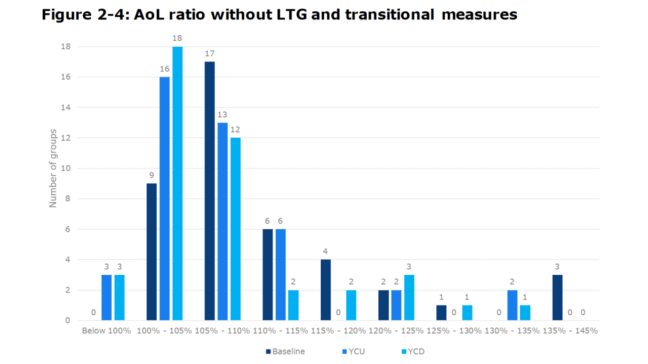

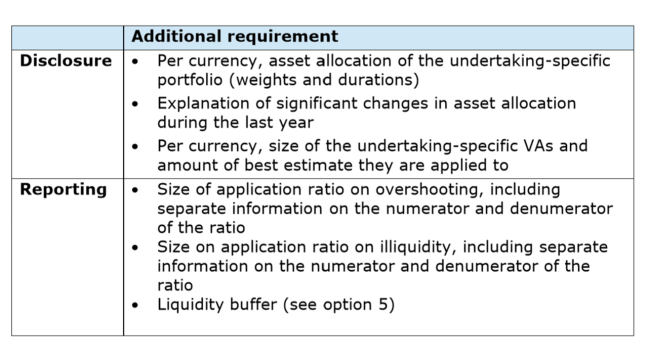

EIOPA considers to choose a later starting point for the extrapolation of risk-free interest rates for the euro or to change the extrapolation method to take into account market information beyond the starting point. Changes are considered with the aim to avoid the underestimation of technical provisions and wrong risk management incentives. The impact on the stability of solvency positions and the financial stability is taken into account. The paper sets out two approaches to calculate the volatility adjustment to the risk-free interest rates. Both approaches include application ratios to mitigate overshooting effects of the volatility adjustment and to take into account the illiquidity characteristics of the insurance liabilities the adjustment is applied to.

- One approach also establishes a clearer split between a permanent component of the adjustment and a macroeconomic component that only exists in times of wide spreads.

- The other approach takes into account the undertakings-specific investment allocation to further address overshooting effects.

Regarding the matching adjustment to risk-free interest rates the proposal is made to recognise in the Solvency Capital Requirement standard formula diversification effects with regard to matching adjustment portfolios. The advice includes proposals to strengthen the public disclosure on the long term guarantees measures and the risk management provisions for those measures.

The advice includes a review of the capital requirements for equity risk and proposals on the criteria for strategic equity investments and the calculation of long-term equity investments. Because of the introduction of the capital requirement on long-term equity investments EIOPA intends to advise that the duration-based equity risk sub-module is phased out.

Technical provisions

EIOPA identified a larger number of aspects in the calculation of the best estimate of technical provisions where divergent practices among undertakings or supervisors exist. For some of these issues, where EIOPA’s convergence tools cannot ensure consistent practices, the advice sets out proposals to clarify the legal framework, mainly on

- contract boundaries,

- the definition of expected profits in future premiums

- and the expense assumptions for insurance undertakings that have discontinued one product type or even their whole business.

With regard to the risk margin of technical provisions transfer values of insurance liabilities, the sensitivity of the risk margin to interest rate changes and the calculation of the risk margin for undertakings that apply the matching adjustment or the volatility adjustment were analysed. The analysis did not result in a proposal to change the calculation of the risk margin.

Own funds

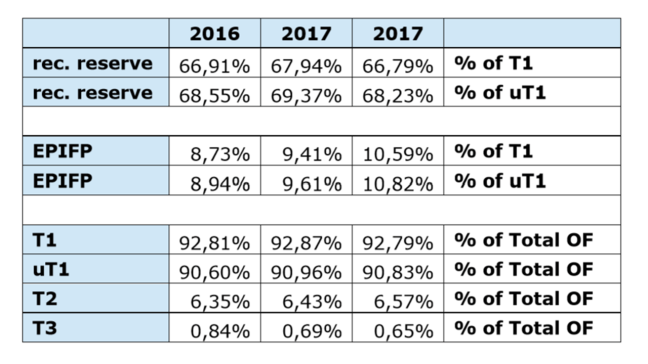

EIOPA has reviewed the differences in tiering and limits approaches within the insurance and banking framework, utilising quantitative and qualitative assessment. EIOPA has found that they are justifiable in view of the differences in the business of both sectors.

Solvency Capital Requirement standard formula

EIOPA confirms its advice provided in 2018 to increase the calibration of the interest rate risk sub-module. The current calibration underestimates the risk and does not take into account the possibility of a steep fall of interest rate as experienced during the past years and the existence of negative interest rates. The review

- of the spread risk sub-module,

- of the correlation matrices for market risks,

- the treatment of non-proportional reinsurance,

- and the use of external ratings

did not result in proposals for change.

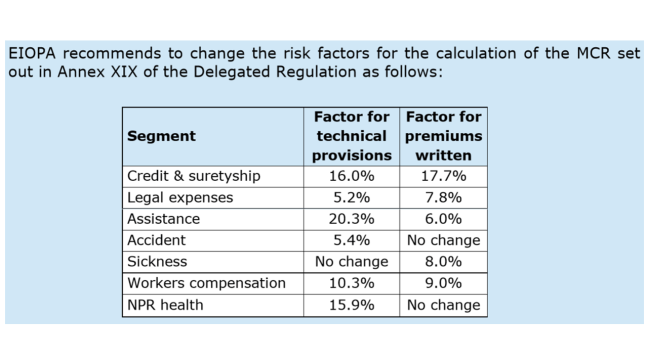

Minimum Capital Requirement

Regarding the calculation of the Minimum Capital Requirement it is suggested to update the risk factors for non-life insurance risks in line with recent changes made to the risk factors for the Solvency Capital Requirement standard formula. Furthermore, proposals are made to clarify the legal provisions on noncompliance with the Minimum Capital Requirement.

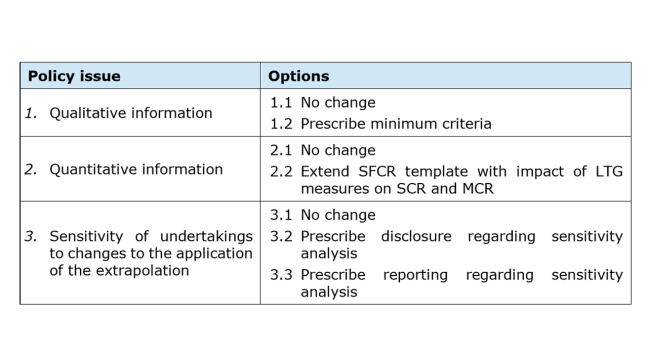

Reporting and disclosure

The advice proposes changes to the frequency of the Regular Supervisory Report to supervisors in order to ensure that the reporting is proportionate and supports risk-based supervision. Suggestions are made to streamline and clarify the expected content of the Regular Supervisory Report with the aim to support insurance undertakings in fulfilling their reporting task avoiding overlaps between different reporting requirements and to ensure a level playing field. Some reporting items are proposed for deletion because the information is also available through other sources. The advice includes a review of the reporting templates for insurance groups that takes into account earlier EIOPA proposals on the templates of solo undertakings and group specificities.

EIOPA proposes an auditing requirement for balance sheet at group level in order to improve the reliability and comparability of the disclosed information. It is also suggested to delete the requirement to translate the summary of that report.

Proportionality

EIOPA has reviewed the rules for exempting insurance undertakings from the Solvency II Directive, in particular the thresholds on the size of insurance business. As a result, EIOPA proposes to maintain the general approach to exemptions but to reinforce proportionality across the three pillars of the Solvency II Directive.

Regarding thresholds EIOPA proposes to double the thresholds related to technical provisions and to allow Member States to increase the current threshold for premium income from the current amount of EUR 5 million to up to EUR 25 million.

EIOPA had reviewed the simplified calculation of the standard formula and proposed improvements in 2018. In addition to that the advice includes proposals to simplify the calculation of the counterparty default risk module and for simplified approaches to immaterial risks. Proposals are made to improve the proportionality of the governance requirements for insurance and reinsurance undertakings, in particular on

- key functions (cumulation with operational functions, cumulation of key functions other than the internal audit, cumulation of key and AMSB function)

- own risk and solvency assessment (ORSA) (biennial report),

- written policies (review at least once every three years)

- and administrative, management and supervisory bodies (AMSB) ( evaluation shall include an assessment on the adequacy of the composition, effectiveness and internal governance of the administrative, management or supervisory body taking into account the nature, scale and complexity of the risks inherent in the undertaking’s business)

Proposals to improve the proportionality in reporting and disclosure of Solvency II framework were made by EIOPA in a separate consultation in July 2019.

Group supervision

EIOPA proposes a number of regulatory changes to address the current legal uncertainties regarding supervision of insurance groups under the Solvency II Directive. This is a welcomed opportunity as the regulatory framework for groups was not very specific in many cases while in others it relies on the mutatis mutandis application of solo rules without much clarifications.

In particular, there are policy proposals to ensure that the

- definitions applicable to groups,

- scope of application of group supervision

- and supervision of intragroup transactions, including issues with third countries

are consistent.

Other proposals focus on the rules governing the calculation of group solvency, including own funds requirements as well as any interaction with the Financial Conglomerates Directive. The last section of the advice focuses on the uncertainties related to the application of governance requirements at group level.

Freedom to provide services and freedom of establishment

EIOPA further provides suggestions in relation to cross border business, in particular to support efficient exchange of information among national supervisory authorities during the process of authorising insurance undertakings and in case of material changes in cross-border activities. It is further recommended to enhance EIOPA’s role in the cooperation platforms that support the supervision of cross-border business.

Macro-prudential policy

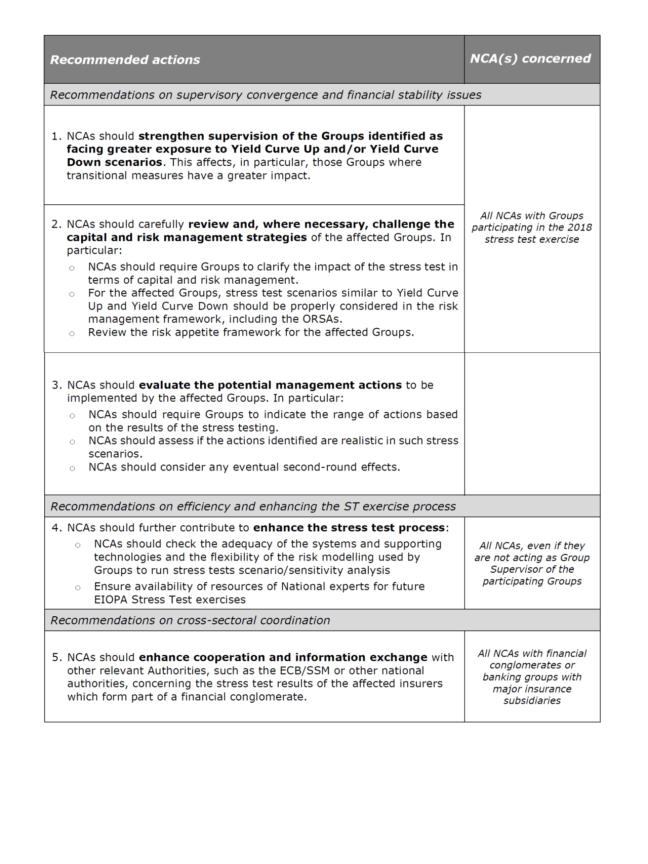

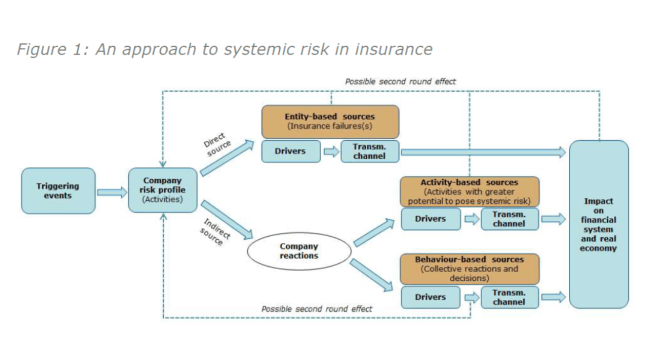

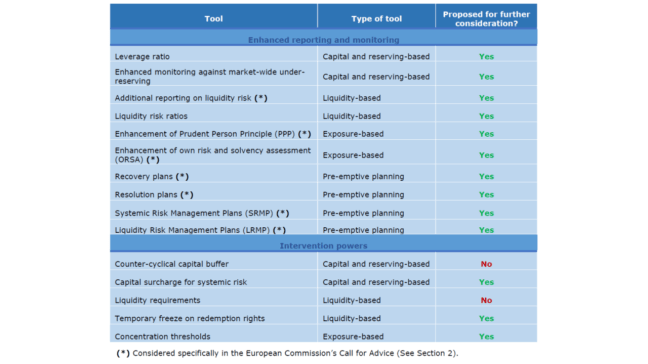

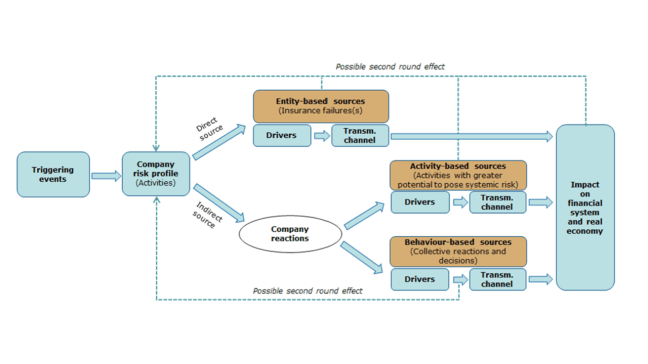

EIOPA proposes to include the macroprudential perspective in the Solvency II Directive. Based on previous work, the advice develops a conceptual approach to systemic risk in insurance and then analyses the current existing tools in the Solvency II framework against the sources of systemic risk identified, concluding that there is the need for further improvements in the current framework.

Against this background, EIOPA proposes a comprehensive framework, covering the tools initially considered by the European Commission (improvements in Own Risk and Solvency Assessment and the prudent person principle, as well as the drafting of systemic risk and liquidity risk management plans), as well as other tools that EIOPA considers necessary to equip national supervisory authorities with sufficient powers to address the sources of systemic risk in insurance. Among the latter, EIOPA proposes to grant national supervisory authorities with the power

- to require a capital surcharge for systemic risk,

- to define soft concentration thresholds,

- to require pre-emptive recovery and resolution plans

- and to impose a temporarily freeze on redemption rights in exceptional circumstances.

Recovery and resolution

EIOPA calls for a minimum harmonised and comprehensive recovery and resolution framework for (re)insurers to deliver increased policyholder protection and financial stability in the European Union. Harmonisation of the existing frameworks and the definition of a common approach to the fundamental elements of recovery and resolution will avoid the current fragmented landscape and facilitate cross-border cooperation. In the advice, EIOPA focuses on the recovery measures including the request for pre-emptive recovery planning and early intervention measures. Subsequently, the advice covers all relevant aspects around the resolution process, such as

- the designation of a resolution authority,

- the resolution objectives,

- the need for resolution planning

- and for a wide range of resolution powers to be exercised in a proportionate way.

The last part of the advice is devoted to the triggers for

- early intervention,

- entry into recovery and into resolution.

Other topics of the review

The review of the ongoing appropriateness of the transitional provisions included in the Solvency II Directive did not result in a proposal for changes. With regard to the fit and proper requirements of the Solvency II Directive EIOPA proposes to clarify the position of national supervisory authorities on the ongoing supervision of propriety of board members and that they should have effective powers in case qualifying shareholders are not proper. Further advice is provided in order to increase the efficiency and intensity of propriety assessments in complex cross-border cases by providing the possibility of joint assessment and use of EIOPA’s powers to assist where supervisors cannot reach a common view.