UK’s Insurance Supervisory Body PRA just published a very interesting paper describing it’s purpose and it’s working principles. Even if Bexit will exclude PRA from EIOPA associated supervisory bodies, this paper should be considered as being landmark as most of the EIOPA associated bodies didn’t go this way of transparency and methodology yet, despite EIOPA having set a framework at least for some of these issues, crucial for insurers to manage thair risk and capital requirements.

« We, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), as part of the Bank of England (‘the Bank’), are the UK’s prudential regulator for deposit-takers, insurance companies, and designated investment firms.

This document sets out how we carry out our role in respect of insurers. It is designed to help regulated firms and the market understand how we supervise these institutions, and to aid accountability to the public and Parliament. The document acts as a standing reference that will be revised and reissued in response to significant legislative and other developments which result in changes to our approach.

This document serves three purposes.

- First, it aids accountability by describing what we seek to achieve and how we intend to achieve it.

- Second, it communicates to regulated insurers what we expect of them, and what they can expect from us in the course of supervision.

- Third, it is intended to meet the statutory requirement for us to issue guidance on how we intend to advance our objectives.

It sits alongside our requirements and expectations as published in the PRA Rulebook and our policy publications.

EU withdrawal

Our approach to advancing these objectives will remain the same as the UK withdraws from the EU. Our main focus is on trying to ensure that the transition to our new relationship with the EU is as smooth and orderly as possible in order to minimise risks to our objectives.

Our approach to advancing our objectives

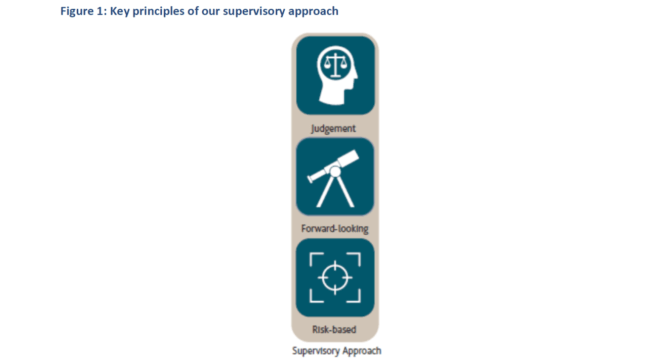

To advance our objectives, our supervisory approach follows three key principles – it is:

- judgement-based;

- forward-looking; and

- focused on key risks.

Across all of these principles, we are committed to applying the principle of proportionality in our supervision of firms.

Identifying risks to our objectives

The intensity of our supervisory activity varies across insurers. The level of supervision principally reflects our judgement of an insurer’s potential impact on policyholders and on the stability of the financial system, its proximity to failure (as encapsulated in the Proactive Intervention Framework (PIF), which is described later), its resolvability and our statutory obligations. Other factors that play a part include the type of business carried out by the insurer and the complexity of the insurer’s business and organisation.

Our risk framework

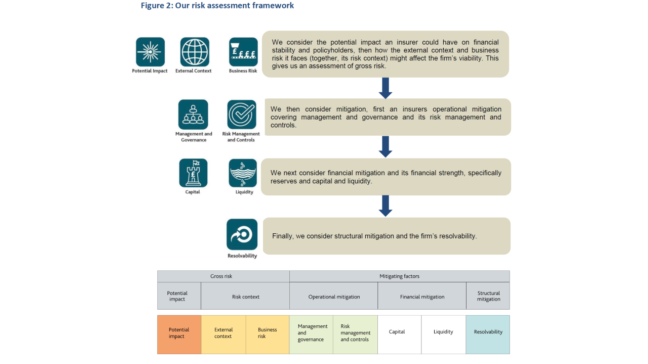

We take a structured approach when forming our judgements. To do this we use a risk assessment framework. The risk assessment framework for insurers is the same as for banks, but is used in a different way, reflecting our additional objective to contribute to securing appropriate policyholder protection, the different risks to which insurers are exposed, and the different way in which insurers fail.

Much of our proposed approach to the supervision of insurers is designed to deliver the supervisory activities which the UK is required to carry out under Solvency II.

The key features of Solvency II are:

- market-consistent valuation of assets and liabilities;

- high quality of capital;

- a forward-looking and risk-based approach to setting capital requirements;

- minimum governance and effective risk management requirements;

- a rigorous approach to group supervision;

- a Ladder of Intervention designed to ensure intervention by us in proportion to the risks that a firm’s financial soundness poses to its policyholders;

- and strong market discipline through firm disclosures.

Some insurers fall outside the scope of the Solvency II Directive (known as non-Directive firms), mainly due to their size. These firms should make themselves familiar with the requirements for non-Directive firms.

Supervisory activity

This section describes how, in practice, we supervise insurers, including information on our highest decision-making body and our approach to authorising new insurers. As part of this, it describes the Proactive Intervention Framework (PIF) and our high-level approach to using our legal powers. For UK insurers, our assessment covers all entities within the consolidated group.

Proactive Intervention Framework (PIF)

Supervisors consider an insurer’s proximity to failure when drawing up a supervisory plan. Our judgement about proximity to failure is captured in an insurer’s position within the PIF.

Judgements about an insurer’s proximity to failure are derived from those elements of the supervisory assessment framework that reflect the risks faced by an insurer and its ability to manage them, namely, external context, business risk, management and governance, risk management and controls, capital, and liquidity. The PIF is not sensitive to an insurer’s potential impact or resolvability.

The PIF is designed to ensure that we put into effect our aim to identify and respond to emerging risks at an early stage. There are five PIF stages, each denoting a different proximity to failure, and every insurer sits in a particular stage at each point in time. When an insurer moves to a higher PIF stage (ie as we determine the insurer’s viability has deteriorated), supervisors will review their supervisory actions accordingly. Senior management of insurers will be expected to ensure that they take appropriate remedial action to reduce the likelihood of failure and the authorities will ensure appropriate preparedness for resolution. The intensity of supervisory resources will increase if we assess an insurer has moved closer to breaching Threshold Conditions, posing a risk of failure and harm to policyholders.

An insurer’s PIF stage is reviewed at least annually and in response to relevant, material developments. (…) »