BP² – the next generation of Business Partner

The role of business partner has become almost ubiquitous in organizations today. According to respondents of this survey, 88% of senior finance professionals already consider themselves to be business partners. This key finding suggests that the silo mentality is breaking down and, at last, departments and functions are joining forces to teach and learn from each other to deliver better performance. But the scope of the role, how it is defined, and how senior finance executives characterize their own business partnering are all open to interpretation. And many of the ideas are still hamstrung by traditional finance behaviors and aspirations, so that the next generation of business partners as agents of change and innovation languish at the bottom of the priority list.

The scope of business partnering

According to the survey, most CFOs see business partnering as a blend of traditional finance and commercial support, while innovation and change are more likely to be seen as outside the scope of business partnering. 57% of senior finance executives strongly agree that a business partner should challenge budgets, plans and forecasts. Being involved in strategy and development followed closely behind with 56% strongly agreeing that it forms part of the scope of business partnering, while influencing commercial decisions was a close third.

The pattern that emerges from the survey is that traditional and commercial elements are given more weight within the scope of business partnering than being a catalyst for change and innovation. This more radical change agenda is only shared by around 36% of respondents, indicating that finance professionals still largely see their role in traditional or commercial terms. They have yet to recognize the finance function’s role in the next generation of business partnering, which can be

- the catalyst for innovation in business models,

- for process improvements

- and for organizational change.

Traditional and commercial business partners aren’t necessarily less important than change agents, but the latter has the potential to add the most value in the longer term, and should at least be in the purview of progressive CFOs who want to drive change and encourage growth.

Unfortunately, this is not an easy thing to change. Finding time for any business partnering can be a struggle, but CFOs spend disproportionately less time on activities that bring about change than on traditional business partnering roles. Without investing time and effort into it, CFOs will struggle to fulfill their role as the next generation of business partner.

Overall 45% of CFOs struggle to make time for any business partnering, so it won’t come as a surprise that, ultimately, only 57% of CFOs believe their finance team efforts as business partners are well regarded by the operational functions.

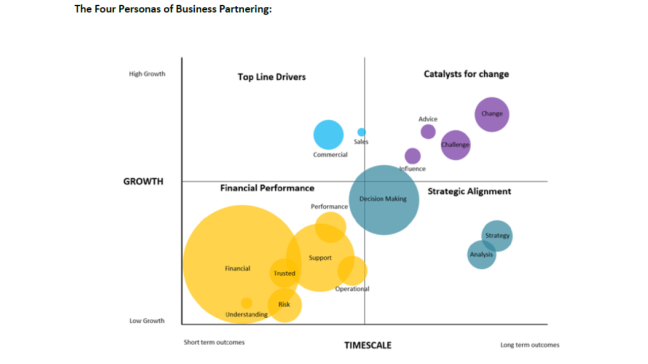

The four personas of business partnering

Ask a room full of CFOs what business partnering means and you’ll get a room full of answers, each one influenced by their personal journey through the changing business landscape. By its very variability, this important business process is being enacted in many ways. FSN, the survey authors, did not seek to define business partnering. Instead, the survey asked respondents to define business partnering in their own words, and the 366 detailed answers were all different. But underlying the diversity were patterns of emphasis that defined four ‘personas’ or styles of business partnering, each exerting its own influence on the growth of the business over time.

A detailed analysis of the definitions and the frequency of occurrence of key phrases and expressions allowed us to plot these personas, their relative weight, together with their likely impact on growth over time.

The size of the bubbles denotes the frequency (number) of times an attribute of business partnering was referenced in the definitions and these were plotted in terms of their likely contribution to growth in the short to long term.

The greatest number of comments by far coalesced around the bottom left-hand quadrant denoting a finance-centric focus on short to medium term outcomes, i.e., the traditional finance business partner. But there was an encouraging drift upwards and rightwards towards the quadrant denoting what we call the next generation of business partner, “BP²” (BP Squared), a super-charged business partner using his or her wide experience, purview and remit to help bring about change in the organization, for example, new business models, new processes and innovative methods of organizational deployment.

Relatively few of the 383 business partners offering definitions of a business partner, concerned themselves with top line growth i.e. with involvement in commercial sales negotiations or the sales pipeline – a critical part of influencing growth.

Finally, surprisingly few finance business partners immersed themselves in strategy development or saw their role as helping to ensure strategic alignment. It suggests that the ongoing transition of the CFO’s role from financial steward to strategic advisor is not as advanced as some would suggest.

Financial Performance Drivers

Most CFOs and senior finance executives define the role of the business partner in traditional financial terms. They are there to explain and illuminate the financial operations, be a trusted, safe pair of hands that manages business risk, and provide s ome operational support. The focus for these CFOs is on communicating a clear understanding of the financial imperative in order to steer the performance of the business prudently.

This ideal reflects the status quo and perpetuates the traditional view of finance, and the role of the CFO. It’s one where the finance function remains a static force, opening up only so far as to allow the rest of the business to see how it functions and make them more accountable to it. While it is obviously necessary for other functions to understand and support a financial strategy, the drawback of this approach is the shortcomings for the business as a whole. Finance-centric business partnering provides some short-term outcomes but does little to promote more than pedestrian growth. It’s better than nothing, but it’s far from the best.

Top-Line Drivers

In the upper quadrant, top line drivers focus on driving growth and sales with a collaborative approach to commercial decision-making. This style of business partnering can have a positive effect on earnings, as improvements in commercial operations and the management of the sales pipeline are translated into revenue.

But while top line drivers are linked to higher growth than financial-focused business partners, the outcome tends to be only short term. The key issue for CFOs is that very few of them even allude to commercial partnerships when defining the scope of business partnering. They ignore the potential for the finance function to help improve the commercial outcomes, like sales or the collection of debt or even a change in business models.

Strategic Aligners

Those CFOs who focus on strategic alignment in their business partnering approach tend to see longer term results. They use analysis and strategy to drive decisionmaking, bringing business goals into focus through partnerships and collaborative working. This business benefit helps to strengthen the foundation of the business in the long term, but it isn’t the most effective in driving substantial growth. And again, there is a paucity of CFOs and senior finance executives who cited strategy development and analysis in their definition of business partnering.

Catalysts for change

The CFOs who were the most progressive and visionary in their definition of business partnering use the role as a catalyst for change. They challenge their colleagues, influence the strategic direction of the business, and generate momentum through change and innovation from the very heart of the finance function. These finance executives get involved in decision-making, and understand the need to influence, advise and challenge in order to promote change. This definition is the one that translates into sustained high growth.

The four personas are not mutually exclusive. Some CFOs view business partnering as a combination of some or all of these attributes. But the preponderance of opinion is clustered around the traditional view of finance, while very little is to do with being a catalyst for change.

How do CFOs characterize their finance function?

However CFOs choose to define the role of business partnering, each function has its own character and style. According to the survey, 17% have a finance-centric approach to business partnering, limiting the relationship to financial stewardship and performance. A further 18% have to settle for a light-touch approach where they are occasionally invited to become involved in commercial decision-making. This means 35% of senior finance executives are barely involved in any commercial decision-making at all.

More positively, the survey showed that 46% are considered to be trusted advisors, and are sought out by operational business teams for opinions before they make big commercial or financial decisions.

But at the apex of the business partnering journey are the change agents, who make up a paltry 19% of the senior finance executives surveyed. These forward thinkers are frequently catalysts for change, suggesting new business processes and areas where the company can benefit from innovation. This is the next stage in the evolution of both the role of the modern CFO and the role of the finance function at the heart of business innovation. We call CFOs in this category BP² (BP Squared) to denote the huge distance between these forward-thinking individuals and the rest of the pack.

Measuring up

Business partnering can be a subtle yet effective process, but it’s not easy to measure. 57% of organizations have no agreed way of measuring the success of business partnering, and 34% don’t think it’s possible to separate and quantify the value added through this collaboration.

Yet CFOs believe there is a strong correlation between business partnering and profitability – with 91% of respondents saying their business partnering efforts significantly add to profitability. While it’s true that some of the outcomes of business partnering are intangible, it is still important to be able to make a direct connection between it and improved performance, otherwise those efforts may be ineffective but are allowed to continue.

One solution is to use 360 degree appraisals, drawing in a wider gamut of feedback including business partners and internal customers to ascertain the effectiveness of the process. Finance business partnering can also be quantified if there are business model changes, like the move from product sales to services, which require a generous underpinning of financial input to be carried out effectively.

Business partnering offers companies a way to inexpensively

- pool all their best resources to generate ideas,

- spark innovation

- and positively add value to the business.

First CFOs need to recognize the importance of business partnering, widen their idea of how it can add value, and then actually set aside the enough time to become agents of change and growth.

Data unlocks business partnering

Data is the most valuable organizational currency in today’s competitive business environment. Most companies are still in the process of working out the best method to collect, collate and use the tsunami of data available to them in order to generate insight. Some organizations are just at the start of their data journey, others are more advanced, and our research confirms that their data profile will make a significant difference to how well their business partnering works.

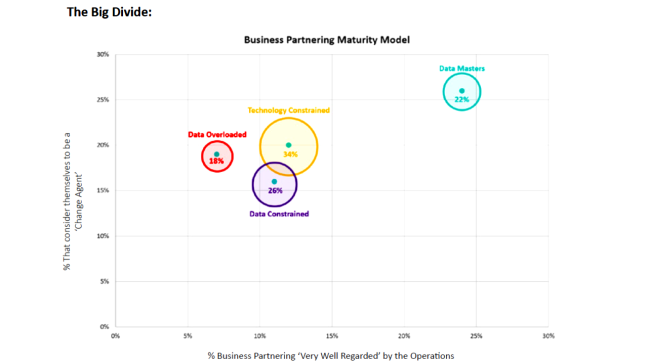

The survey asked how well respondents’ data supported the role of business partnering, and the responses showed that 18% were data overloaded. This meant business partners have too many conflicting data sources and poor data governance, leaving them with little actual usable data to support the partnering process.

26% were data constrained, meaning they cannot get hold of the data they need to drive insight and decision making.

And a further 34% were technology constrained, muddling through without the tech savvy resources or tools to fully exploit the data they already have. These senior finance executives may know the data is there, sitting in an ERP or CRM system, but can’t exploit it because they lack the right technology tools.

The final 22% have achieved data mastery, where they actively manage their data as a corporate asset, and have the tools and resources to exploit it in order to give their company a competitive edge.

This means 78% overall are hampered by data constraints and are failing to use data effectively to get the best out of their business partnering. While the good intentions are there, it is a weak partnership because there is little of substance to work with.

The diagram above is the Business Partnering Maturity Model as it relates to data. It illustrates that there is a huge gap in performance between how effective data masters and data laggards are at business partnering.

The percentage of business partners falling into each category of data management (‘data overloaded’, ‘data constrained,’ etc) has been plotted together with how well these finance functions feel that business partnering is regarded by the operational units as well as their perceived influence on change.

The analysis reveals that “Data masters” are in a league of their own. They are significantly more likely to be well regarded by the operations and are more likely to act as change agents in their business partnering role.

We know from FSN’s 2018 Innovation in Financial Reporting survey that data masters, who similarly made up around one fifth of senior finance executives surveyed, are also more innovative. That research showed they were more likely to have worked on innovative projects in the last three years, and were less likely to be troubled by obstacles to reporting and innovation.

Data masters also have a more sophisticated approach to business partnering. They’re more likely to be change agents, are more often seen as a trusted advisor and they’re more involved in decision making. Interestingly, two-thirds of data masters have a formal or agreed way to measure the success of business partnering, compared to less than 41% of data constrained CFOs, and 36% of technology constrained and data overloaded finance executives. They’re also more inclined to perform 360 degree appraisals with their internal customers to assess the success of their business partnering. This means they can monitor and measure their success, which allows them to adapt and improve their processes.

The remainder, i.e. those that have not mastered their data, are clustered around a similar position on the Business Partnering Maturity Model, i.e., there is little to separate them around how well they are regarded by operational business units or whether they are in a position to influence change.

The key message from this survey is that data masters are the stars of the modern finance function, and it is a sentiment echoed through many of FSN’s surveys over the last few years.

The Innovation in Financial Reporting survey also found that data masters outperformed their less able competitors in three key performance measures that are indicative of financial health and efficiency:

- they close their books faster,

- reforecast quicker and generate more accurate forecasts,

- and crucially they have the time to add value to the organization.

People, processes and technology

So, if data is the key to driving business partnerships, where do the people, processes and technology come in? Business partnering doesn’t necessarily come naturally to everyone. Where there is no experience of it in previous positions, or if the culture is normally quite insular, sometimes CFOs and senior finance executives need focused guidance. But according to the survey, 77% of organizations expect employees to pick up business partnering on the job. And only just over half offer specialized training courses to support them.

Each company and department or function will be different, but businesses need to support their partnerships, either with formal structures or at the very least with guidance from experienced executives to maximize the outcome. Meanwhile processes can be a hindrance to business partnering in organizations where there is a lack of standardization and automation. The survey found that 71% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that a lack of automation hinders the process of business partnering.

This was followed closely by a lack of standardization, and a lack of unification, or integration in corporate systems. Surprisingly the constraints of too many or too complex spreadsheets only hindered 61% of CFOs, the lowest of all obstacles but still a substantial stumbling block to effective partnerships. The hindrances reflect the need for better technology to manage the data that will unlock real inter-departmental insight, and 83% of CFOs said that better software to support data analytics is their most pressing need when supporting effective business partnerships.

Meanwhile 81% are looking to future technology to assist in data visualization to make improvements to their business partnering.

This echoes the findings of FSN’s The Future of Planning, Budgeting and Forecasting survey which identified users of cutting edge visualization tools as the most effective forecasters. Being able to visually demonstrate financial data and ideas in an engaging and accessible way is particularly important in business partnering, when the counterparty doesn’t work in finance and may have only rudimentary knowledge of complex financial concepts.

Data is a clear differentiator. Business partners who can access, analyze and explain organizational data are more likely to

- generate real insight,

- engage their business partners

- and become a positive agent of change and growth.