For the past several years, fund managers have faced virtually the same challenge: how to put record amounts of raised capital to work productively amid heavy competition for assets and soaring purchase price multiples. Top performers recognize that the only effective response is to get better—and smarter.

We’ve identified four ways leading firms are doing so.

- A growing number of (General Partners) GPs are facing down rising deal multiples by using buy-and-build strategies as a form of multiple arbitrage—essentially scaling up valuable new companies by acquiring smaller, cheaper ones.

- The biggest firms, meanwhile, are beating corporate competitors at their own game by executing large-scale strategic mergers that create value out of synergies and combined operational strength.

- GPs are also discovering the power of advanced analytics to shed light on both value and risks in ways never before possible.

- And they are once again exploring adjacent investment strategies that take advantage of existing capabilities, while resisting the temptation to stray too far afield.

Each of these approaches will require an investment in new skills and capabilities for most firms. Increasingly, however, continuous improvement is what separates the top-tier firms from the rest.

Buy-and-build: Powerful strategy, hard to pull off

While buy-and-build strategies have been around as long as private equity has, they’ve never been as popular as they are right now. The reason is simple: Buy-and-build can offer a clear path to value at a time when deal multiples are at record levels and GPs are under heavy pressure to find strategies that don’t rely on traditional tailwinds like falling interest rates and stable GDP growth. Buying a strong platform company and building value rapidly through well-executed add-ons can generate impressive returns.

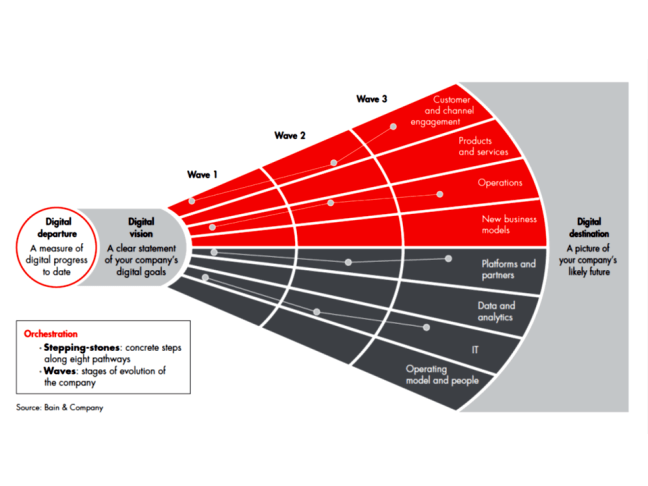

As the strategy becomes more and more popular, however, GPs are discovering that doing it well is not as easy as it looks. When we talk about buy-and-build, we don’t mean portfolio companies that pick up one or two acquisitions over the course of a holding period. We also aren’t referring to onetime mergers meant to build scale or scope in a single stroke. We define buy-and-build as an explicit strategy for building value by using a well-positioned platform company to make at least four sequential add-on acquisitions of smaller companies. Measuring this activity with the data available isn’t easy. But you can get a sense of its growth by looking at add-on transactions. In 2003, just 21% of all add-on deals represented at least the fourth acquisition by a single platform company. That number is closer to 30% in recent years, and in 10% of the cases, the add-on was at least the 10th sequential acquisition.

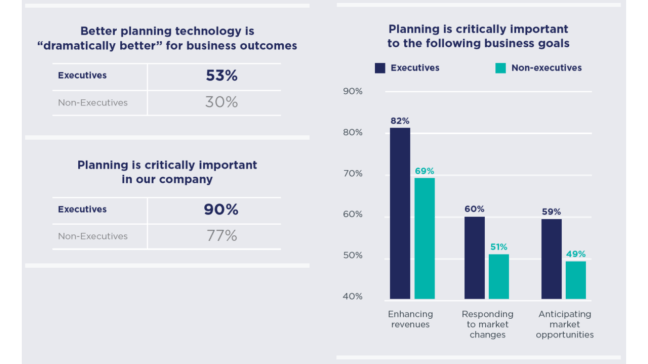

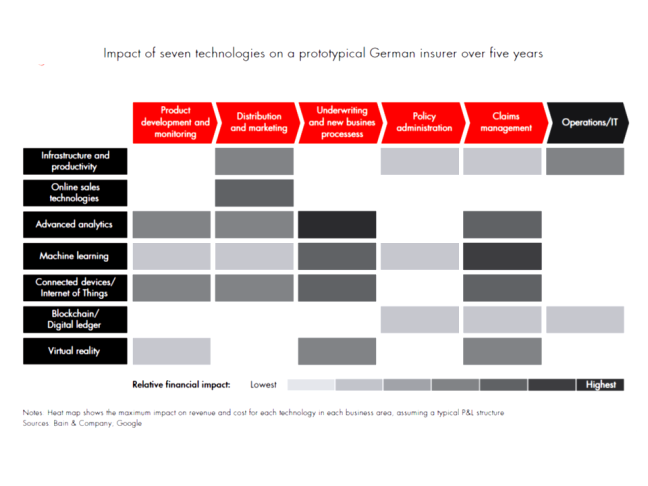

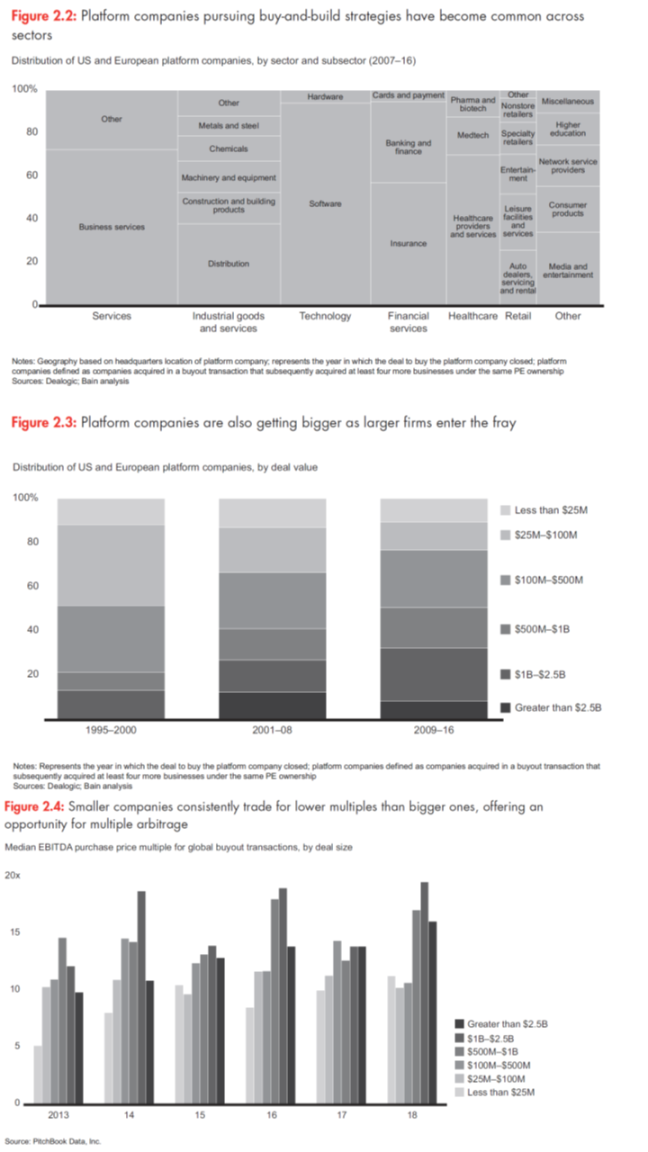

Buy-and-build strategies are showing up across a wide swath of industries (see Figure 2.2). They are also moving out of the small- to middle-market range as larger firms target larger platform companies (see Figure 2.3). They are popular because they offer a powerful antidote to soaring deal multiples. They give GPs a way to take advantage of the market’s tendency to assign big companies higher valuations than smaller ones (see Figure 2.4). A buy-and-build strategy allows a GP to justify the initial acquisition of a relatively expensive platform company by offering the opportunity to tuck in smaller add-ons that can be acquired for lower multiples later on. This multiple arbitrage brings down the firm’s average cost of acquisition, while putting capital to work and building additional asset value through scale and scope. At the same time, serial acquisitions allow GPs to build value through synergies that reduce costs or add to the top line. The objective is to assemble a powerful new business such that the whole is worth significantly more than the parts.

Having coinvested in or advised on hundreds of buy-and-build deals over the past 20 years, we’ve learned that sponsors tend to underestimate what it takes to win. We’ve seen buy-and-build strategies offer firms a number of compelling paths to value creation, but we’ve also seen these approaches badly underperform other strategies. Every deal is different, of course, but there are patterns to success.

The most effective buy-and-build strategies share several important characteristics.

Too many attempts at creating value through buy-and-build founder on the shoals of bad planning. What looks like a slam-dunk strategy rarely is. Winning involves assessing the dynamics at work in a given sector and using those insights to weave together the right set of assets. The firms that get it right understand three things going in:

- Deep, holistic diligence is critical. In buy-and-build, due diligence doesn’t start with the first acquisition. The most effective practitioners diligence the whole opportunity, not just the component parts. That means understanding how the strategy will create value in a given sector using a specific platform company to acquire a well-defined type of add-on. Are there enough targets in the sector, and is it stable enough to support growth? Does the platform already have the right infrastructure to make acquisitions, or will you need to build those capabilities? Who are the potential targets, and what do they add? Deep answers to questions like these are a necessary prerequisite to evaluating the real potential of a buy-and-build thesis.

- Execution is as important as the investment. Great diligence leads to a great playbook. The best firms have a clear plan for what to buy, how to integrate it, and what roles fund management and platform company leadership will play. This starts with building a leadership team that is fit for purpose. It also means identifying bottlenecks (e.g., IT systems, integration team) and addressing them quickly. There are multiple models that can work—some rely on extensive involvement from deal teams, while others assume strong platform management will take the wheel. But given the PE time frame, the imperative is to have a clear plan up front and to accelerate acquisition activity during what inevitably feels like a very short holding period.

- Pattern recognition counts. Being able to see what works comes with time and experience. Learning, however, relies on a conscious effort to diagnose what worked well (or didn’t) with past deals. This forensic analysis should include the choice of targets, as well as how decisions along each link of the investment value chain (either by fund management or platform company management) created or destroyed value. Outcomes improve only when leaders use insights from past deals to make better choices the next time.

At a time when soaring asset prices are dialing up the need for GPs to create value any way they can, an increasing number of firms are turning to buy-and-build strategies. The potential for value creation is there; capturing it requires

- sophisticated due diligence,

- a clear playbook,

- and strong, experienced leadership.

Merger integration: Stepping up to the challenge

PE funds are increasingly turning to large-scale M&A to solve what has become one of the industry’s most intractable problems—record amounts of money to spend and too few targets. GPs have put more money to work over the past five years than during any five-year period in the buyout industry’s history. Still, dry powder, or uncalled capital, has soared 64% over the same period, setting new records annually and ramping up pressure on PE firms to accelerate the pace of dealmaking.

One reason for the imbalance is hardly a bad problem: Beginning in 2014, enthusiastic investors have flooded buyout funds with more than $1 trillion in fresh capital. Another issue, however, poses a significant conundrum: PE firms are too often having to withdraw from auctions amid fierce competition from strategic corporate buyers, many of which have a decided advantage in bidding. Given that large and mega-buyout funds of $1.5 billion or more hold two-thirds of the uncalled capital, chipping away at the mountain of dry powder will require more and bigger deals by the industry’s largest players (see Figure 2.6). Very large public-to-private transactions are on the rise for precisely this reason.

But increasingly, large funds are looking to win M&A deals by recreating the economics that corporate buyers enjoy. This involves using a platform company to hunt for large-scale merger partners that add strategic value through scale, scope or both.

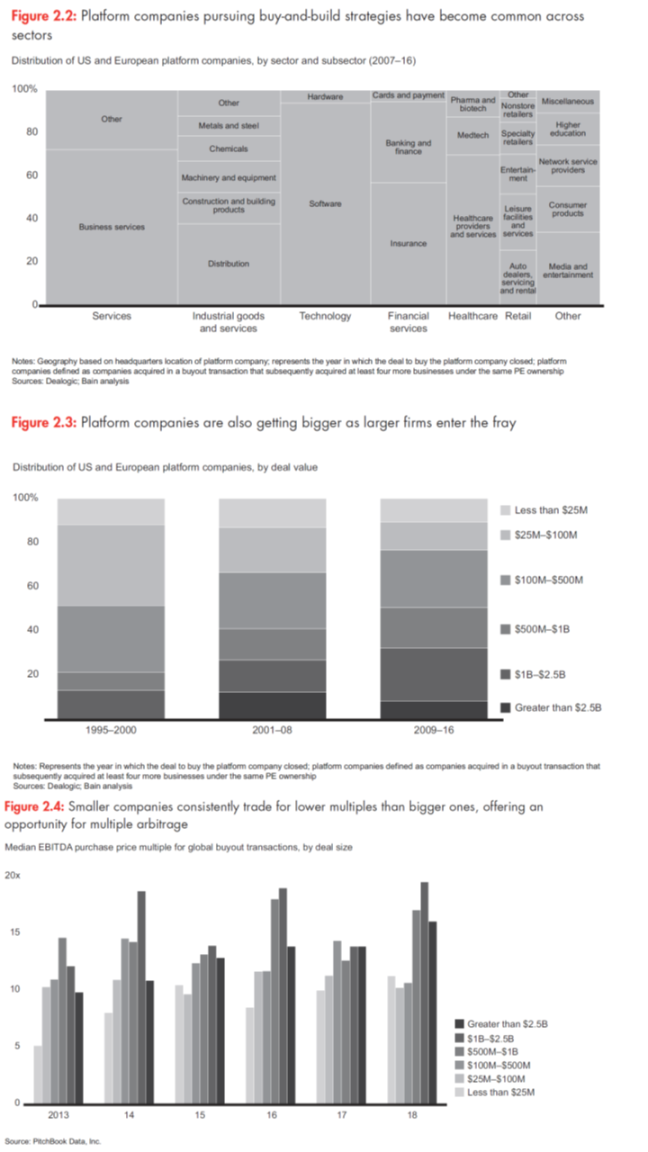

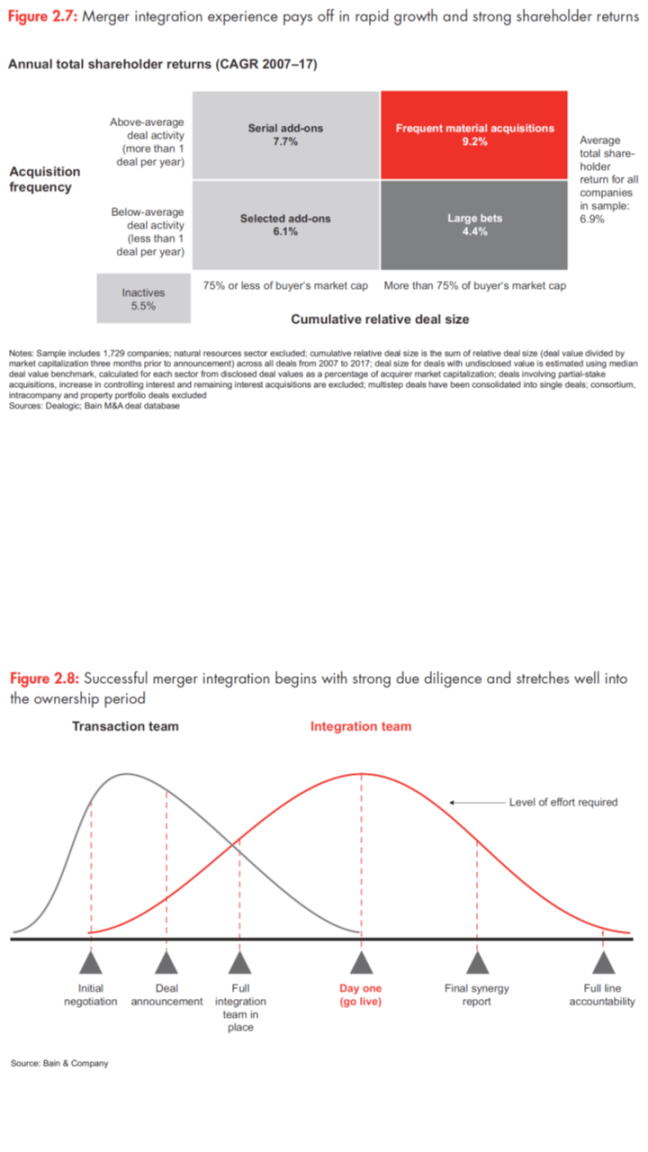

Making it all work, of course, is another matter. Large-scale, strategic M&A solves one problem for large PE firms by putting a lot of capital to work at once, but it also creates a major challenge: capturing value by integrating two or more complex organizations into a bigger one that makes strategic and operational sense. Bain research shows that, while there is clear value in making acquisitions large enough to have material impact on the acquirer, the success rate is uneven and correlates closely to buyer experience (see Figure 2.7). The winners do this sort of deal relatively frequently and turn large-scale M&A into a repeatable model. The laggards make infrequent big bets, often in an attempt to swing for the fences strategically. Broken deals tend to fail because firms stumble over merger integration. They enter the deal without an integration thesis or try to do everything at once. They don’t identify synergies with any precision, or fail to capture the ones they have identified. GPs neglect to sort out leadership issues soon enough, or they underestimate the challenge of merging systems and processes. For many firms, large-scale merger integration presents a steep learning curve.

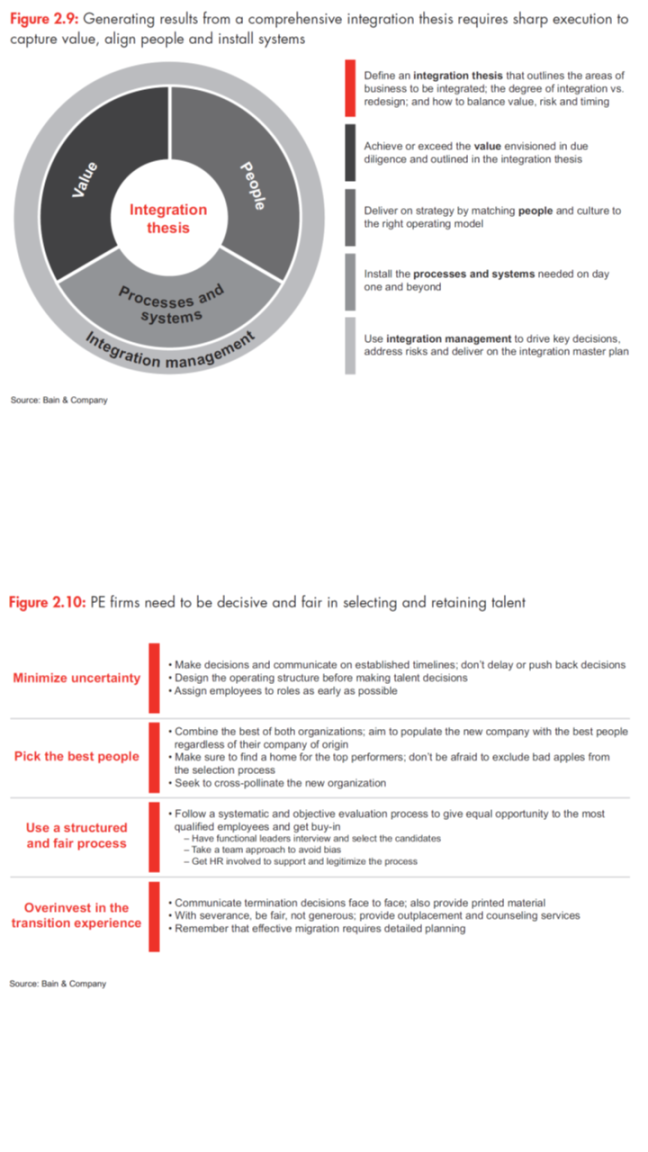

In our experience, success in a PE context requires a different way of approaching three key phases of the value-creation cycle:

- due diligence,

- the post-announcement period

- and the post-close integration period (see Figure 2.8).

In many ways, what happens before the deal closes is almost as important as what happens after a firm assumes ownership. Top firms invest in deep thinking about integration from the outset of due diligence. And they bring a sharp focus to how the firm can move quickly and decisively during the holding period to maximize time to value.

In a standalone due diligence process, deal teams focus on a target’s market potential, its competitiveness, and opportunities to cut costs or improve performance. In a merger situation, those things still matter, but since the firm’s portfolio company should have a good understanding of the market already, the diligence imperative switches to a bottom-up assessment of the potential synergies:

- Measuring synergies. Synergies typically represent most of a merger deal’s value, so precision in underwriting them is critical. High-level benchmarks aren’t sufficient; strong diligence demands rigorous quantification. The firm has to decide which synergies are most important, how much value they represent and how likely they are to be captured within the deal’s time frame. A full understanding of the synergies available in a deal like this allows a firm to bid as aggressively as possible. It often gives the deal team the option to share the value of synergies with the seller in the form of a higher acquisition price. On the other hand, the team also needs to account for dis-synergies—the kinds of negative outcomes that can easily lead to value destruction.

- Tapping the balance sheet. One area of potential synergies often underappreciated by corporate buyers is the balance sheet. Because companies in the same industry frequently share suppliers and customers, combining them presents opportunities to negotiate better contracts and improve working capital. There might also be a chance to reduce inventory costs by pooling inventory, consolidating warehouses or rationalizing distribution centers. At many target companies, these opportunities represent low-hanging fruit, especially at corporate spin-offs, since parent companies rarely manage the working capital of individual units aggressively. Combined businesses can also trim capital expenditures.

- Managing the “soft” stuff. While these balance sheet issues play to a GP’s strong suit, people and culture issues usually don’t. PE firms aren’t known for their skill in diagnosing culture conflicts, retaining talent or working through the inevitable HR crises raised by integration. Firms often view these so-called soft issues as secondary to the things they can really measure. Yet people problems can quickly undermine synergies and other sources of value, not to mention overall performance of the combined company. To avoid these problems, it helps to focus on two things in due diligence. First, which of the target company’s core capabilities need to be preserved, and what will it take to retain the top 10 people who deliver them? Second, does the existing leadership team—on either side of the transaction—understand how to integrate a business? The firm needs to know whether those responsible for leading the integration have done it before, whether they’ve been successful and whether the firm can trust them to do it successfully in this situation. PE owners are often more involved in integration than the board of a typical corporation. It’s important not to overstep, however. Bigfooting the management team is a sure way to spur a talent exodus. For PE firms eager to put money to work, great diligence in a merger context is critical. It should not only answer questions such as “How much value can we underwrite?” but also evaluate whether to do the deal at all. Deal teams have to resist the urge to make an acquisition simply because the clock is ticking. Corporate buyers often take years to identify and court the right target. While it’s true that PE firms rarely have that luxury, no amount of merger integration prowess can make up for acquiring a company that just doesn’t fit.

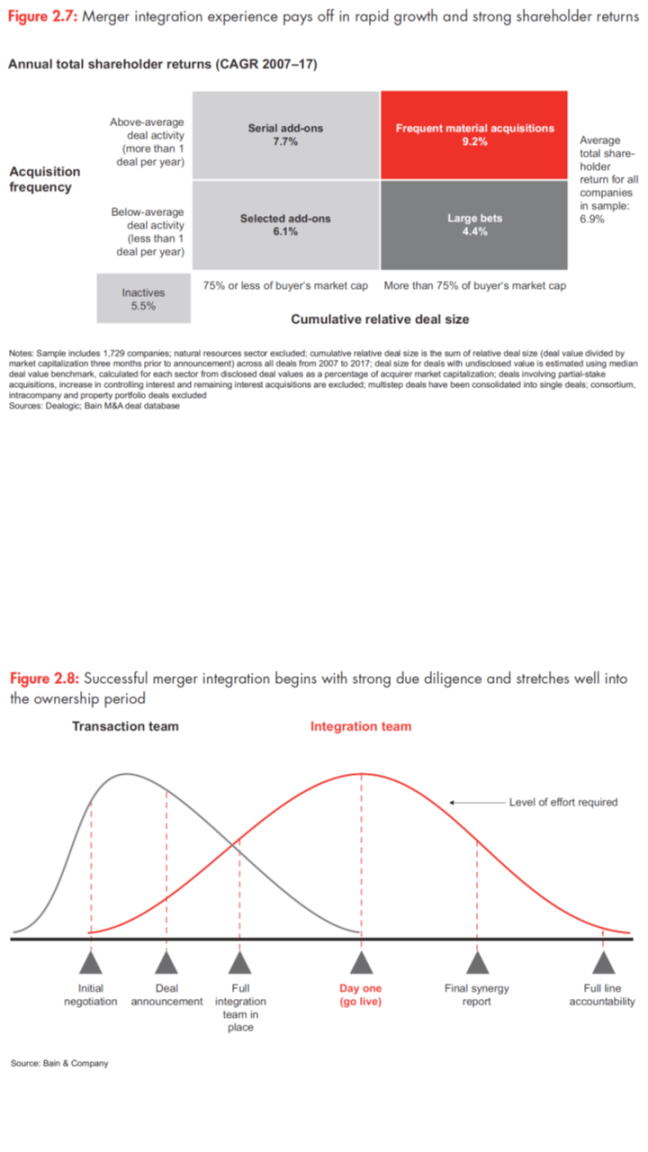

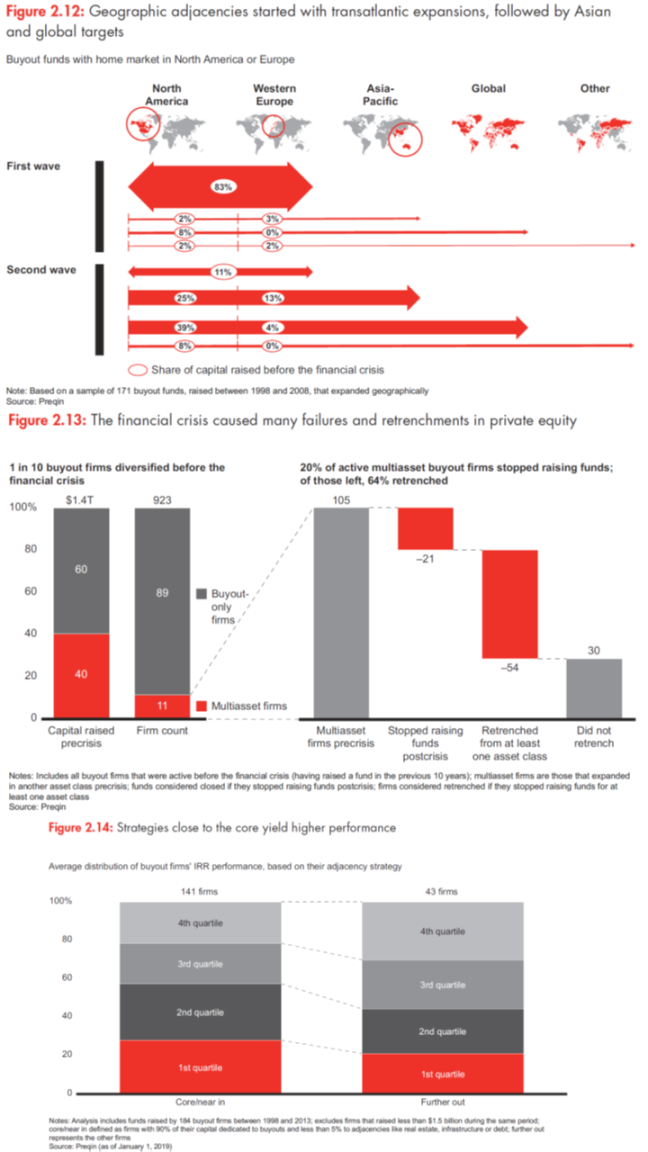

Once the hard work of underwriting value and generating a robust integration thesis is complete, integration planning begins in earnest. A successful integration has three major objectives:

- capturing the identified value,

- managing the people issues,

- and integrating processes and systems (see Figure 2.9).

This is where the Integration Management Office (IMO) needs to shine. As the central leadership office, its role is to keep the integration effort on track and to hit the ground running on day one. Pre- and post-close, the IMO

- monitors risks (including interdependences),

- tracks and reports on team progress,

- resolves conflicts,

- and works to achieve a consistent drumbeat of decisions and outcomes.

It manages dozens of integration teams, each with its own detailed work plan, key performance indicators and milestones. It also communicates effectively to all stakeholders.

- Capturing value. An often-underappreciated aspect of the early merger integration process is the art of maintaining continuity in the base business. Knitting together the two organizations and realizing synergies is essential, but value can be lost quickly if a chaotic integration process gets in the way of running the core. Management needs to reserve focus for day-to-day operations, keeping close tabs on customers and vendors, and intervening quickly if problems crop up. At the same time, it is important to validate and resize the value-creation initiatives and synergies identified in diligence. The team has to create a new value roadmap that articulates in detail the value available and how to capture it. This document redefines the size of the prize based on real data. It should be cascaded down through the organization to inform detailed team-level work plans.

- Tackling the people challenge. Integrating large groups of people is very often the most challenging— and overlooked—aspect of bringing two companies together. Mergers are emotionally charged events that take employees out of their comfort zone. While top leadership may be thinking about pulling the team together to find value, the people on the ground, understandably, are focused on what it means for them. The change disrupts everybody; nobody knows what’s coming, and human nature being what it is, people often shut down. Getting ahead of potential disaster involves three critical areas of focus:

- retaining key talent,

- devising a clear operating model

- and solving any culture issues.

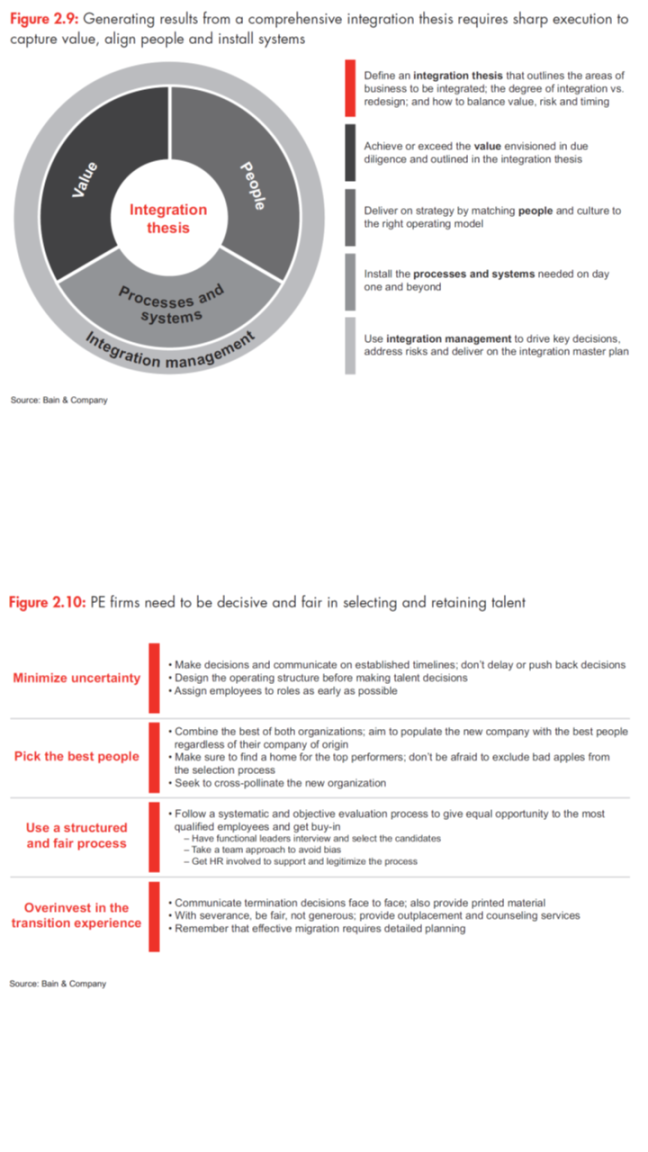

Talent retention boils down to identifying who creates the most value at the company and understanding what motivates them. Firms need to isolate the top 50 to 100 individuals most responsible for the combined company’s value and devise a retention plan tailored to each one. Keeping these people on board will likely involve financial incentives, but it may be more important to present these stars with a clear vision for the future and how they can bring it to life by excelling in mission-critical roles. It is also essential to be decisive and fair in making talent decisions (see Figure 2.10). Assigning these roles is an outgrowth of a larger challenge: devising a fit-for-purpose operating model that aligns with the overall vision for the company. This is the set of organizational elements that helps translate business strategy into action. It defines roles, reporting relationships and decision rights, as well as accountabilities. Whether this new model works will have a lot to do with how well leadership manages the cultural integration challenge. Nothing can destroy value faster than internal dysfunction, but getting it right can be a delicate exercise.

- Processes and systems. The final integration imperative—designing and implementing the new company’s processes and systems—is all about anticipating how things will get done in the new company and building the right infrastructure to support that activity. PE firms must consider which processes to integrate and which to leave alone. The north star on these decisions is which efforts will directly accrue to value within the deal time frame and which can wait. Often, this means designing an interim and an end-state solution, ensuring delivery of critical functionality now while laying the foundation for the optimal long-term solution. Integrating IT systems requires a similar decision-making process, focused on what will create the most value. If capturing synergies in the finance department involves cutting headcount within several financial planning and analysis teams, that might only happen when they are on a single system. Likewise, if the optimal operating model calls for a fully integrated sales and marketing team, then working from a single CRM system makes sense. Most PE firms are hyperfocused on the expense involved in these sorts of decisions. They weigh the onetime costs of integration against a sometimes-vague potential return and ultimately decide not to push forward. This may be a mistake. Taking a more expansive view of potential value often pays off. Early investments in IT, for instance, may look expensive in the short run. But to the extent that they make possible future investments in better capabilities or continued acquisitions, they can be invaluable.

Adjacency strategy: Taking another shot at diversification

Given the amount of capital gushing into private equity, it’s not surprising that PE firms are diversifying their fund offerings by launching new strategies. The question is whether this wave of diversification can produce better results than the last one. History has shown that expanding thoughtfully into the right adjacencies can deliver great results. But devoting time, capital and talent to strategies that stray too far afield can quickly sap performance.

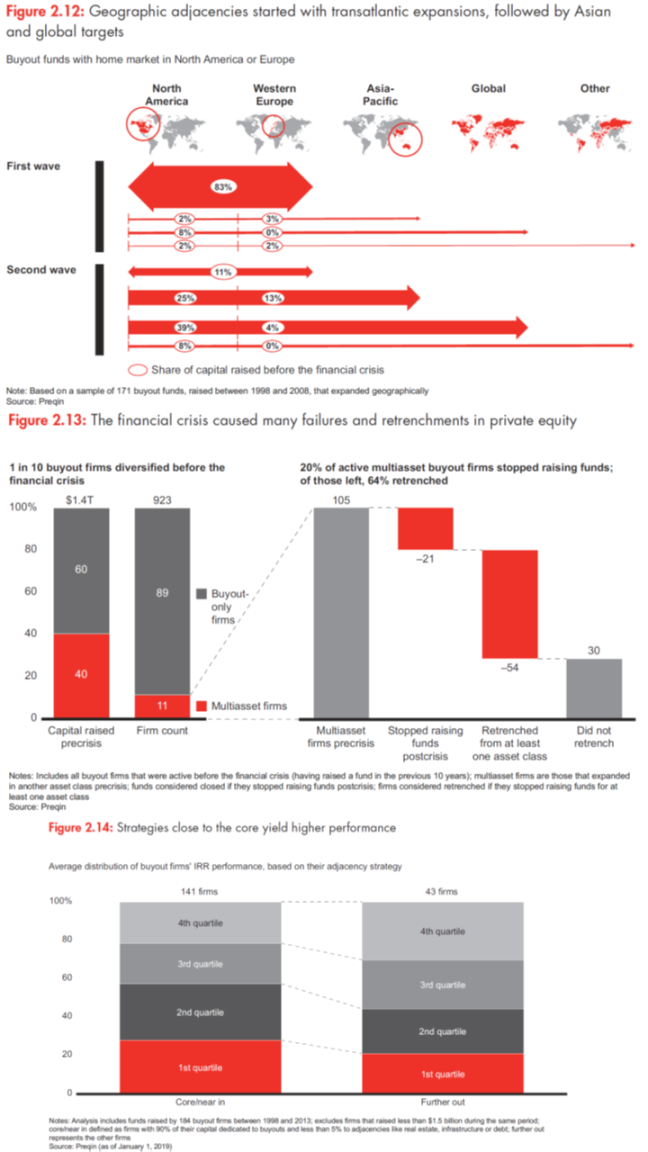

In the mid-1990s, the industry faced a similar challenge in putting excess capital to work. As institutions and other large investors scoured the investment landscape for returns, they increased allocations to alternative investments, including private equity. Larger PE funds eagerly took advantage of the situation by branching into different geographies and asset classes. This opened up new fee and revenue streams, and allowed the funds to offer talented associates new opportunities. Funds first expanded geographically, typically by crossing the Atlantic from the US to Europe, then extending into Asia and other regions by the early 2000s (see Figure 2.12). Larger firms next began to experiment with asset class diversification, creating

- growth and venture capital funds,

- real estate funds,

- mezzanine financing

- and distressed debt vehicles.

Many PE firms found it more challenging to succeed in new geographies and especially in different asset classes. Credit, infrastructure, real estate and hedge funds held much appeal, in part because they were less correlated with equity markets and offered new pools of opportunity. But critically, most of these asset classes also required buyout investors to get up to speed on very different capabilities, and they offered few synergies. Compared with buyouts, most of these adjacent asset classes had a different investment thesis, virtually no deal-sourcing overlap, little staff or support-function cost sharing, and a different Limited Partners (LP) risk profile. To complicate matters, PE firms found that many of these adjacencies offered lower margins than their core buyout business. Some came with lower fees, and others did not live up to performance targets. Inherently lower returns for LPs made it difficult to apply the same fee structures as for traditional buyouts. To create attractive total economics and pay for investment teams, PE firms needed to scale up some of these new products well beyond what they might do in buyouts. That, in turn, threatened to change the nature of the firm.

For large firms that ultimately went public, like KKR, Blackstone and Apollo, the shift in ownership intensified the need to produce recurring, predictable streams of fees and capital gains. Expanding at scale in different asset classes became an imperative. And today, buyouts represent a minority of their assets under management.

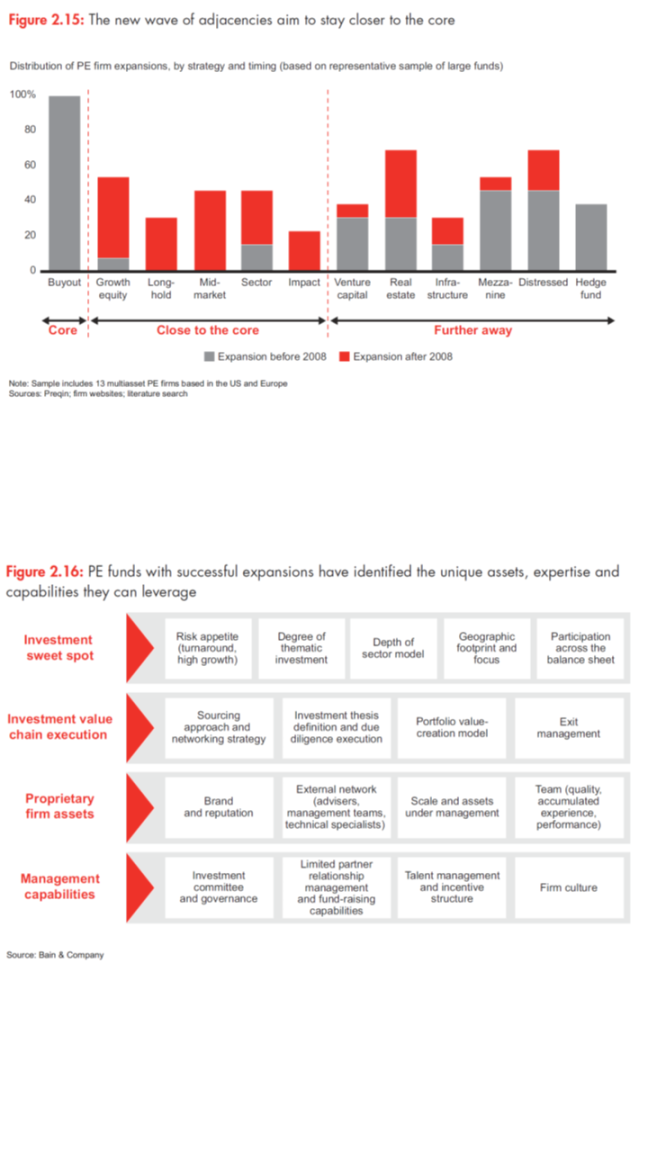

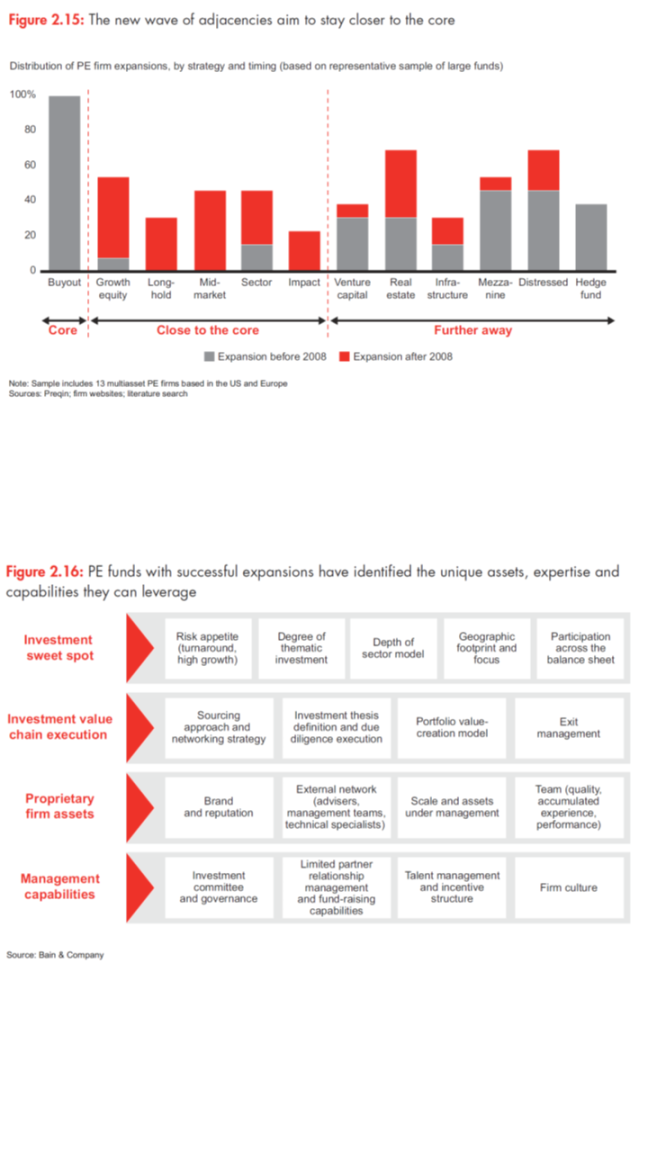

As other firms pursued diversification, however, the combination of different capabilities and lower returns wasn’t always worth the trade-off. When the global financial crisis hit, money dried up, causing funds to retrench from adjacencies that did not work well—either because of a lack of strategic rationale or because an asset class struggled overall. Of the 100 buyout firms that added adjacencies before 2008 (roughly 1 in 10 firms active then), 20% stopped raising capital after the crisis, and nearly 65% of those left had to pull out from at least one of their asset classes (see Figure 2.13).

Diversification, it became clear, was trickier to navigate than anticipated. Succeeding in any business that’s far from a company’s core capabilities presents a stiff challenge—and private equity is no different. To test this point, we looked at a sample of funds launched between 1998 and 2013 by 184 buyout firms for which we had performance data, each of which had raised at least $1.5 billion during that period. We found that, when it comes to maintaining a high level of returns, staying close to the core definitely matters. Our study defined “core/near-in” firms as those that dedicated at least 90% of their raised capital to buyouts and less than 5% to adjacencies (including infrastructure, real estate and debt). We compared them to firms that moved further away from the core (dedicating more than 5% to adjacencies). The results: On average, 28% of core/near-in firms’ buyout funds generated top-quartile IRR performance, vs. 21% for firms that moved further afield (see Figure 2.14). The IRR gap for geographic diversification is more muted, because making such moves is generally easier than crossing asset types. But expanding into a new country or region does require developing or acquiring a local network, as well as transferring certain capabilities. And the mixed IRR record that we identified still serves as a caution: Firms need to be clear on what they excel at and exactly how their strengths could transfer to adjacent spaces.

With a record amount of capital flowing into private equity in recent years, GPs again face the question of how to deploy more capital through diversification. While a few firms, such as Hellman & Friedman, remain fully committed to funding their core buyout strategy, not many can achieve such massive scale in one asset class. As a result, a new wave of PE products is finding favor with both GPs and LPs. Top performers are considering adjacencies that are one step removed from the core, rather than two or three steps removed. The best options take advantage of existing platforms, investment themes and expertise. They’re more closely related to what PE buyout firms know how to do, and they also hold the prospect of higher margins for the GP and better net returns for LPs. In other words, these new products are a different way to play a familiar song.

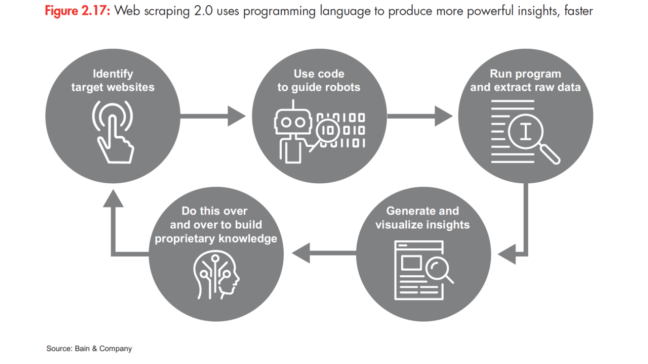

There are any number of ways for firms to diversify, but several stand out in today’s market (see Figure 2.15):

- Long-hold funds have a life span of up to 15 years or so, offering a number of benefits. Extending a fund’s holding period allows PE firms to better align with the longer investment horizon of sovereign wealth funds and pension funds. It also provides access to a larger pool of target companies and allows for flexibility on exit timing with fewer distractions. These funds represent a small but growing share of total capital.

- Growth equity funds target minority stakes in growing companies, usually in a specific sector such as technology or healthcare. Though the field is getting more crowded, growth equity has been attractive given buyout-like returns, strong deal flow and less competition than for other types of assets. Here, a traditional buyout firm can transfer many of its core capabilities. Most common in Asia, growth equity has been making inroads in the US and Europe of late.

- Sector funds focus exclusively on one sector in which the PE firm has notable strengths. These funds allow firms to take advantage of their expertise and network in a defined part of the investing landscape.

- Mid-market funds target companies whose enterprise value typically ranges between $50 million and $500 million, allowing the firm to tap opportunities that would be out of scope for a large buyout fund.

All of the options described here have implications for a PE firm’s operating model, especially in terms of retaining talent, communicating an adjacency play to LPs, avoiding cannibalization of the firm’s traditional buyout funds and sorting out which deal belongs in which bucket.

GPs committed to adjacency expansion should ask themselves a few key questions:

- Do we have the resident capabilities to execute well on this product today, or can we add them easily?

- Does the asset class leverage our cost structure?

- Do our customers—our LPs—want these new products?

- Can we provide the products through the same channels?

- Have we set appropriate expectations for the expansion, both for returns and for investments?

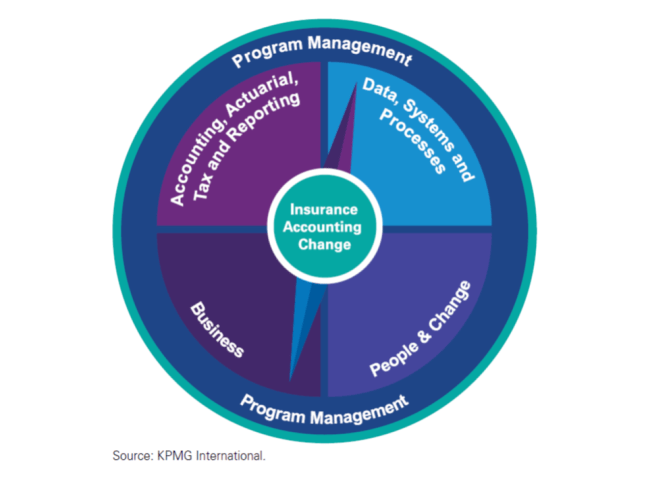

Clear-eyed answers to these questions will determine whether, and which, adjacencies make sense. The past failures and retrenchments serve as a reminder that investing too far afield risks distracting GPs from their core buyout funds. Instead, a repeatable model consists of understanding which strengths a fund can export and thoughtfully mapping those strengths to the right opportunities (see Figure 2.16).

Adjacency expansion will remain a popular tack among funds looking for alternative routes to put their capital to work. Funds that leverage their strengths in a disciplined, structured way stand the best chance of reaping healthy profits from expansion.

Advanced analytics: Delivering quicker and better insights

At a time when PE firms face soaring asset prices and heavy competition for deals, advanced analytics can help them derive the kinds of proprietary insights that give them an essential edge against rivals. These emerging technologies can offer fund managers rapid access to deep information about a target company and its competitive position, significantly improving the firm’s ability to assess opportunities and threats. That improves the firm’s confidence in bidding aggressively for companies it believes in—or walking away from a target with underlying issues.

What’s clear, however, is that advanced analytics isn’t for novices. Funds need help in taking advantage of these powerful new tools. The technology is evolving rapidly, and steady innovation creates a perplexing array of options. Using analytics to full advantage requires staying on top of emerging trends, building relationships with the right vendors, and knowing when it makes sense to unleash teams of data scientists, coders and statisticians on a given problem. Bain works with leading PE firms to sort through these issues, evaluate opportunities and build effective solutions. We see firms taking advantage of analytics in several key areas.

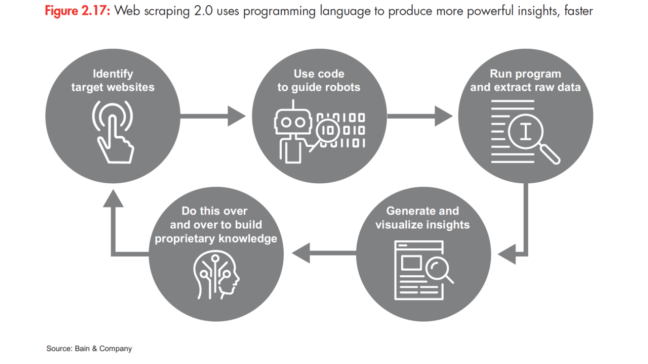

Many PE funds already use scraping tools to extract and analyze data from the web. Often, the goal is to evaluate customer sentiment or to obtain competitive data on product pricing or assortment. New tools make it possible to scrape the web much more efficiently, while gaining significantly deeper insights. Deployed properly, they can also give GPs the option to build proprietary databases over time by gathering information daily, weekly or at other intervals. Using a programming language such as Python, data scientists can direct web robots to search for and extract specific data much more quickly than in the past (see Figure 2.17). With the right code and the right set of target websites, new tools can also allow firms to assemble proprietary databases of historical information on pricing, assortment, geographic footprint, employee count or organizational structure. Analytics tools can access and extract visible and hidden data (metadata) as frequently as fund managers find useful.

Most target companies these days sell through online channels and rely heavily on digital marketing. Fewer do it well. The challenge for GPs during due diligence is to understand quickly if a target company could use digital technology more effectively to create new growth opportunities. Post-acquisition, firms often need similar insights to help a portfolio company extract more value from its digital marketing strategy. Assessing a company’s digital positioning—call it a digital X-ray—is a fast and effective way to gain these insights. For well-trained teams, it requires a few hours to build the assessment, and it can be done from the outside in—before a fund even bids. It is also relatively easy to ask for access to a target company’s Google AdWords and Google Analytics platforms. That can produce a raft of digital metrics and further information on the target’s market position.

One challenge for PE funds historically has been accessing data from large networks or from scattered and remote locations. But new tools let deal teams complete such efforts in a fraction of the time and cost.

One issue that PE deal teams often ponder in evaluating companies is traffic patterns around retail networks, manufacturing facilities and transport hubs. Is traffic rising or declining? What’s the potential to increase it? In some industries, it’s difficult to track such data, especially for competitors. But high-definition satellite images or drones can glean insights from traffic flows over time.

Another advantage of analytics tools is the ability to see around corners, helping fund managers anticipate how disruptive new technologies or business models may change the market. Early signs of disruption are notoriously hard to quantify. Traditional measures such as client satisfaction or profitability won’t ring the warning bells soon enough. Even those who know the industry best often fail to anticipate technological disruptions. With access to huge volumes of data, however, it’s easier to track possible warning signs, such as the level of innovation or venture capital investment in a sector. That’s paved the way for advanced analytics tools that allow PE funds to spot early signals of industry disruption, understand the level of risk and devise effective responses. These insights can be invaluable, enabling firms to account for disruption as they formulate bidding strategies and value-creation plans.

These are just a few of the ways that PE firms can apply advanced analytics to improve deal analysis and portfolio company performance. We believe that the burst of innovation in this area will have profound implications for how PE funds go about due diligence and manage their portfolio companies. But most funds will need to tap external expertise to stay on top of what’s possible. A team-based approach that assembles the right expertise for a given problem helps ensure that advanced analytics tools deliver on their promise.

Click here to access Bain’s Private Equity Report 2019