Where was the board? As a corporate director, imagine you find yourself in one of these difficult situations:

- Unexpected financial losses mount as your bank faces a sudden collapse during a 1-in-100-year economic crisis.

- Customers leave and profits drop year after year as a new technology start-up takes over your No. 1 market position.

- Negative headlines and regulatory actions besiege your company following undesirable tweets and other belligerent behavior from the CEO.

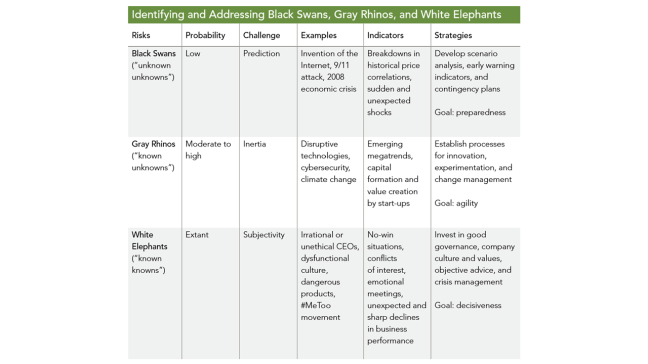

These scenarios are not hard to imagine when you consider what unfolded before the boards of Lehman Brothers, Blockbuster, Tesla, and others. In the context of disruptive risks, these events can be referred to as black swans, gray rhinos, and white elephants, respectively. While each has unique characteristics, the commonality is that all of these risks can have a major impact on a company’s profitability, competitive position, and reputation.

In a VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous) world, boards need to expand their risk governance and oversight to include disruptive risks. This article addresses three fundamental questions:

- What are black swans, gray rhinos, and white elephants?

- Why are they so complex and difficult to deal with?

- How should directors incorporate these disruptive risks as part of their oversight?

Why are companies so ill prepared for disruptive risks? There are three main challenges:

- standard enterprise risk management (ERM) programs may not capture them;

- they each present unique characteristics and complexities;

- and cognitive biases prevent directors and executives from addressing them.

Standard tools used in ERM, including risk assessments and heat maps, are not timely or dynamic enough to capture unconventional and atypical risks. Most risk quantification models—such as earnings volatility and value-at-risk models—measure potential loss within a 95 percent or 99 percent confidence level. Black swan events, on the other hand, may have a much smaller than 0.1 percent chance of happening. Gray rhinos and white elephants are atypical risks that may have no historical precedent or operational playbooks. As such, disruptive risks may not be adequately addressed in standard ERM programs even if they have the potential to destroy the company. The characteristics and complexities of each type of disruptive risk are unique. The key challenge with black swans is prediction. They are outliers that were previously unthinkable. That is not the case with gray rhinos, since they are generally observable trends. With gray rhinos the main culprit is inertia: companies see the megatrends charging at them, but they can’t seem to mitigate the risk or seize the opportunity. The key issue with white elephants is subjectivity. These no-win situations are often highly charged with emotions and conflicts. Doing nothing is usually the easiest choice but leads to the worst possible outcome. While it is imperative to respond to disruptive risks, cognitive biases can lead to systematic errors in decision making. Behavioral economists have identified dozens of biases, but several are especially pertinent in dealing with disruptive risks:

- Availability and hindsight bias is the underestimation of risks that we have not experienced and the overestimation of risks that we have. This bias is a key barrier to acknowledging atypical risks until it is too late.

- Optimism bias is a tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes and to underestimate the likelihood of negative outcomes. This is a general issue for risk management, but it is especially problematic in navigating disruptive risks.

- Confirmation bias is the preference for information that is consistent with one’s own beliefs. This behavior prevents us from processing new and contradictory information, or from responding to early signals.

- Groupthink or herding occurs when individuals strive for group consensus at the cost of objective assessment of alternative viewpoints. This is related to the sense of safety in being part of a larger group, regardless if their actions are rational or not.

- Myopia or short-termism is the tendency to have a narrow view of risks and a focus on short-term results (e.g., quarterly earnings), resulting in a reluctance to invest for the longer term.

- Status quo bias is a preference to preserve the current state. This powerful bias creates inertia and stands in the way of appropriate actions.

To overcome cognitive biases, directors must recognize that they exist and consider how they impact decision making. Moreover,

- board diversity,

- objective data,

- and access to independent experts

can counter cognitive biases in the boardroom.

Recommendations for Consideration

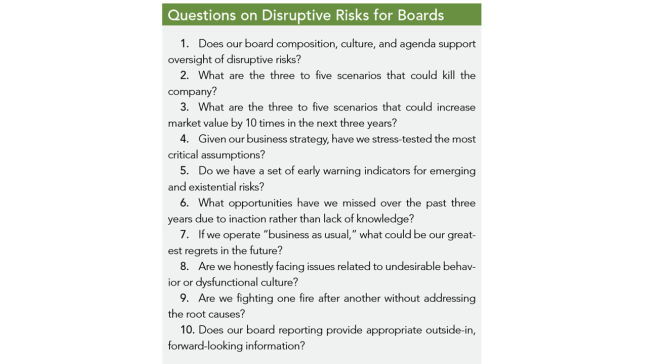

How should directors help their organizations navigate disruptive risks? They can start by asking the right questions in the context of the organization’s business model and strategy. The chart below lists 10 questions that directors can ask themselves and management.

In addition, directors should consider the following five recommendations to enhance their risk governance and oversight:

- Incorporate disruptive risks into the board agenda. The full board should discuss the potential impact of disruptive risks as part of its review of the organization’s strategy to create sustainable long-term value. Disruptive risks may also appear on the agenda of key committees, including the risk committee’s assessment of enterprise risks, the audit committee’s review of risk disclosures, the compensation committee’s determination of executive incentive plans, and the governance committee’s processes for addressing undesirable executive behavior. The key is to explicitly incorporate disruptive risks into the board’s oversight and scope of work.

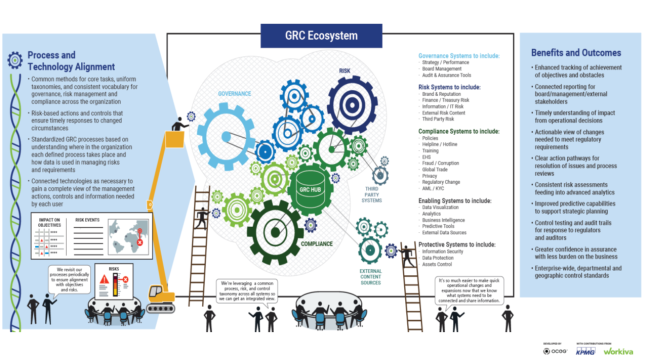

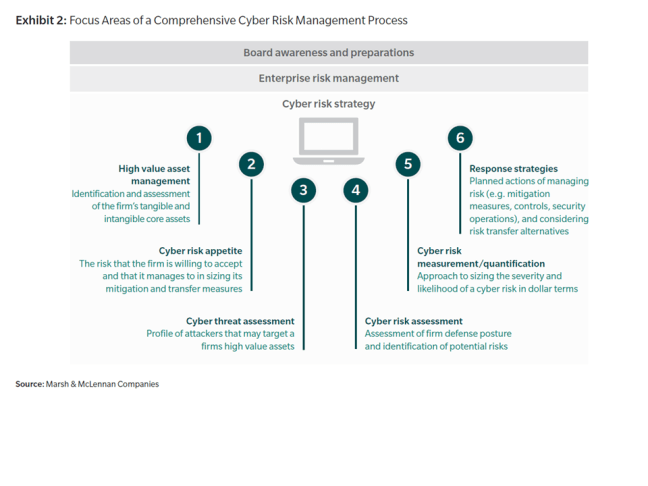

- Ensure that fundamental ERM practices are effective. Fundamental ERM practices—risk policy and analytics, management strategies, and metrics and reporting—provide the baseline from which disruptive risks can be considered. As an example, the definition of risk appetite can inform discussions of loss tolerance relative to disruptive risks. As an early step, the board should ensure that the overall ERM framework is robust and effective. Otherwise, the organization may fall victim to “managing risk by silo” and miss critical interdependencies between disruptive risks and other enterprise risks.

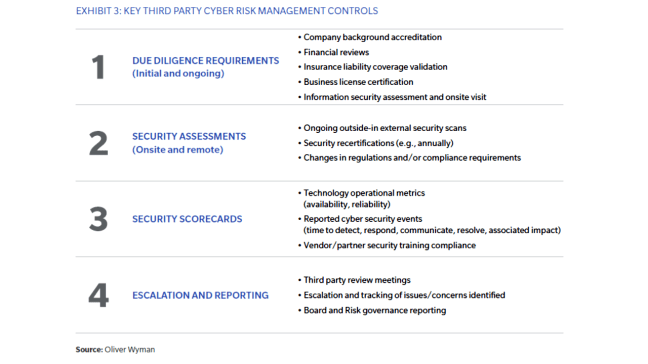

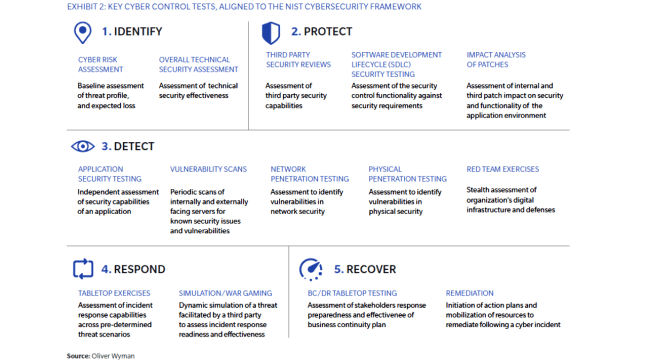

- Consider scenario planning and analysis. Directors should recognize that basic ERM tools may not fully capture disruptive risks. They should consider advocating for, and participating in, scenario planning and analysis. This is akin to tabletop exercises for cyber-risk events, except much broader in scope. Scenario analysis can be a valuable tool to help companies put a spotlight on hidden risks, generate strategic insights on performance drivers, and identify appropriate actions for disruptive trends. The objective is not to predict the future, but to identify the key assumptions and sensitivities in the company’s business model and strategy. In addition to scenario planning, dynamic simulation models and stress-testing exercises should be considered.

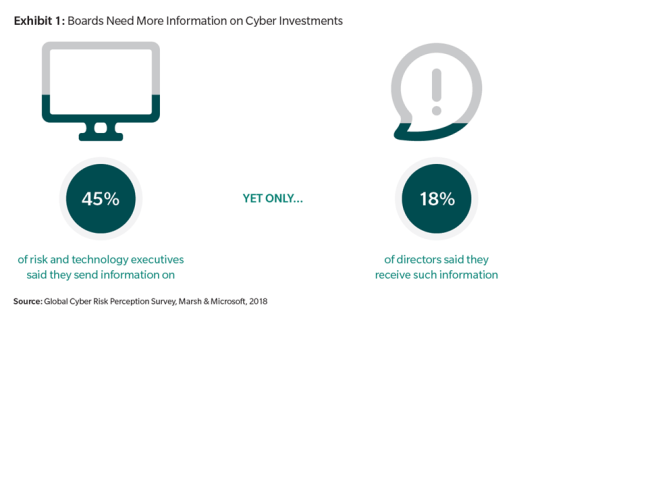

- Ensure board-level risk metrics and reports are effective. The quality of risk reports is key to the effectiveness of board risk oversight. Standard board risk reports often are comprised of insufficient information: historical loss and event data, qualitative risk assessments, and static heat maps. An effective board risk report should include quantitative analyses of risk impacts to earnings and value, key risk metrics measured against risk appetite, and forwardlooking information on emerging risks. By leveraging scenario planning, the following reporting components can enhance disruptive risk monitoring:

- Market intelligence data that provides directors with useful “outside-in” information, including key business and industry developments, consumer and technology trends, competitive actions, and regulatory updates.

- Enterprise performance and risk analysis including key performance and risk indicators that quantify the organization’s sensitivities to disruptive risks.

- Geo-mapping that highlights global “hot spots” for economic, political, regulatory, and social instability. This can also show company-specific risks such as third-party vendor, supply chain, and cybersecurity issues.

- Early-warning indicators that provide general or scenariospecific signals with respect to risk levels, effectiveness of controls, and external drivers.

- Action triggers and plans to facilitate timely discussions and decisions in response to disruptive risks.

- Strengthen board culture and governance. To effectively oversee disruptive risks, the board must be fit for purpose. This requires creating a board culture that considers nontraditional views, questions key assumptions, and supports continuous improvement. Good governance practices should be in place in the event a white elephant appears. For example, what is the board protocol and playbook if the CEO acts inappropriately? In the United States, the 25th Amendment and impeachment clauses are in place ostensibly to remove a reprehensible president. Does the organization have procedures to remove a reprehensible CEO?

The following chart summarizes the key characteristics, examples, indicators, and strategies for identifying and addressing black swans, gray rhinos, and white elephants. The end goal should be to enhance oversight of disruptive risks and counter the specific challenges that are presented. To mitigate the unpredictability of black swans, the company should develop contingency plans with a focus on preparedness. To overcome inertia and deal with gray rhinos, the company needs to establish organizational processes and incentives to increase agility. To balance subjectivity and confront white elephants, directors should invest in good governance and objective input that will support decisiveness.

The Opportunity for Boards

In a VUCA world, corporate directors must expand their traditional risk oversight beyond well-defined strategic, operational, and financial risks. They must consider atypical risks that are hard to predict, easy to ignore, and difficult to address. While black swans, gray rhinos, and white elephants may sound like exotic events, directors could enhance their recognization of them by reflecting on their own experiences serving on boards.

Given their experiences, directors should provide a leading voice to improve oversight of disruptive risks. They have a comparative advantage in seeing the big picture based on the nature of their work— part time, detached from day-to-day operations, and with experience gained from serving different companies and industries. Directors can add significant value by providing guidance to management and helping them see the forest for the trees. Finally, there is an opportunity side to risk. There are positive and negative black swans. A company can invest in the positive ones and be prepared for the negative ones. For every company that is trampled by a gray rhino, another company is riding it to a higher level of performance. By addressing the white elephant in the boardroom, a company can remediate an unspoken but serious problem. In the current environment, board oversight of disruptive risks represents both a risk management imperative and a strategic business opportunity.

Click here to access NACD’s summary