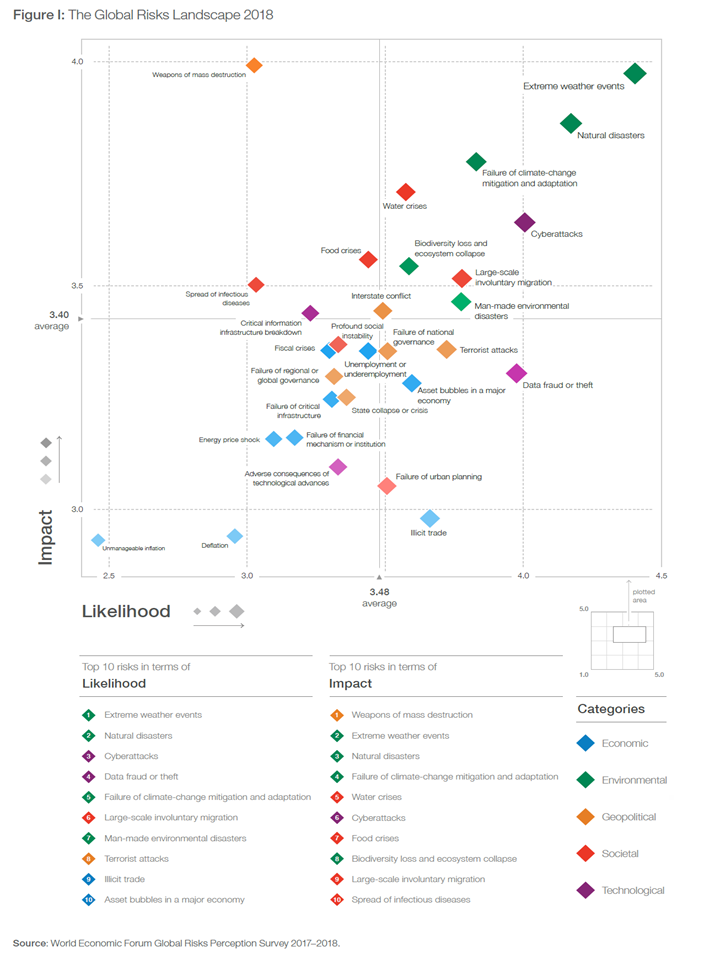

The role of the risk manager has always been to understand and manage threats to a given business. In theory, this involves a very broad mandate to capture all possible risks, both current and future. In practice, however, some risk managers are assigned to narrower, siloed roles, with tasks that can seem somewhat disconnected from key business objectives.

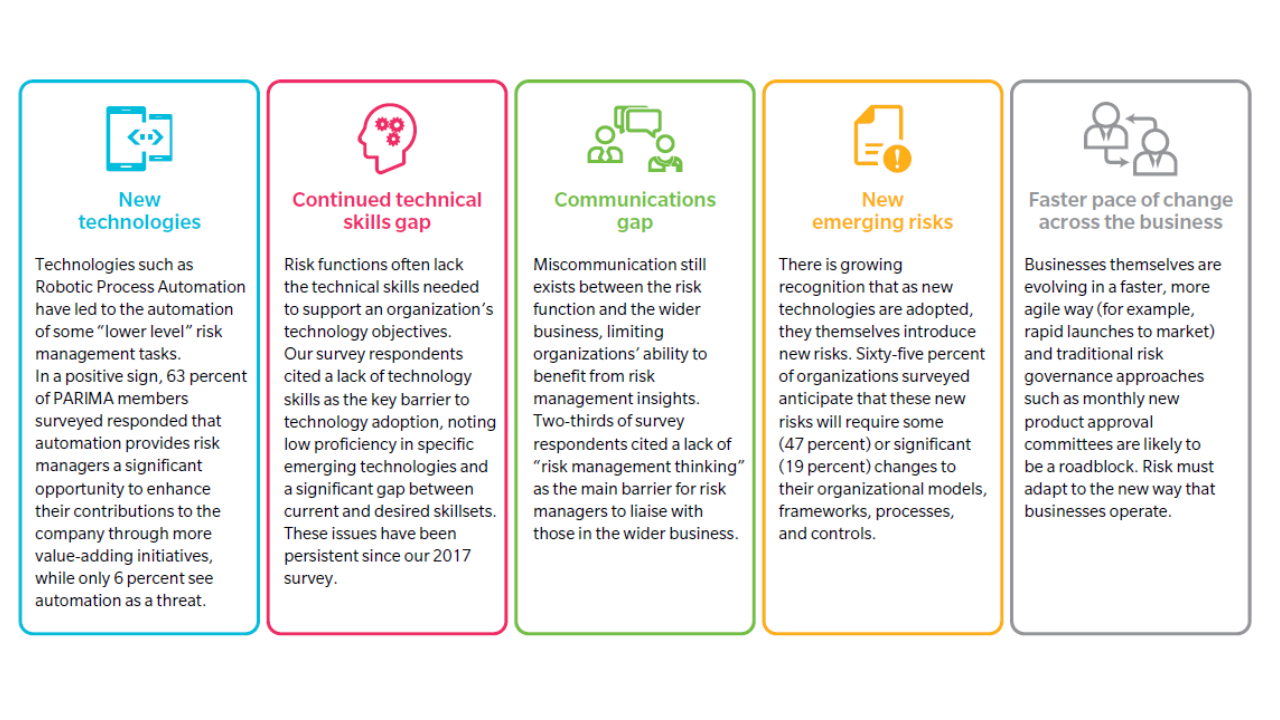

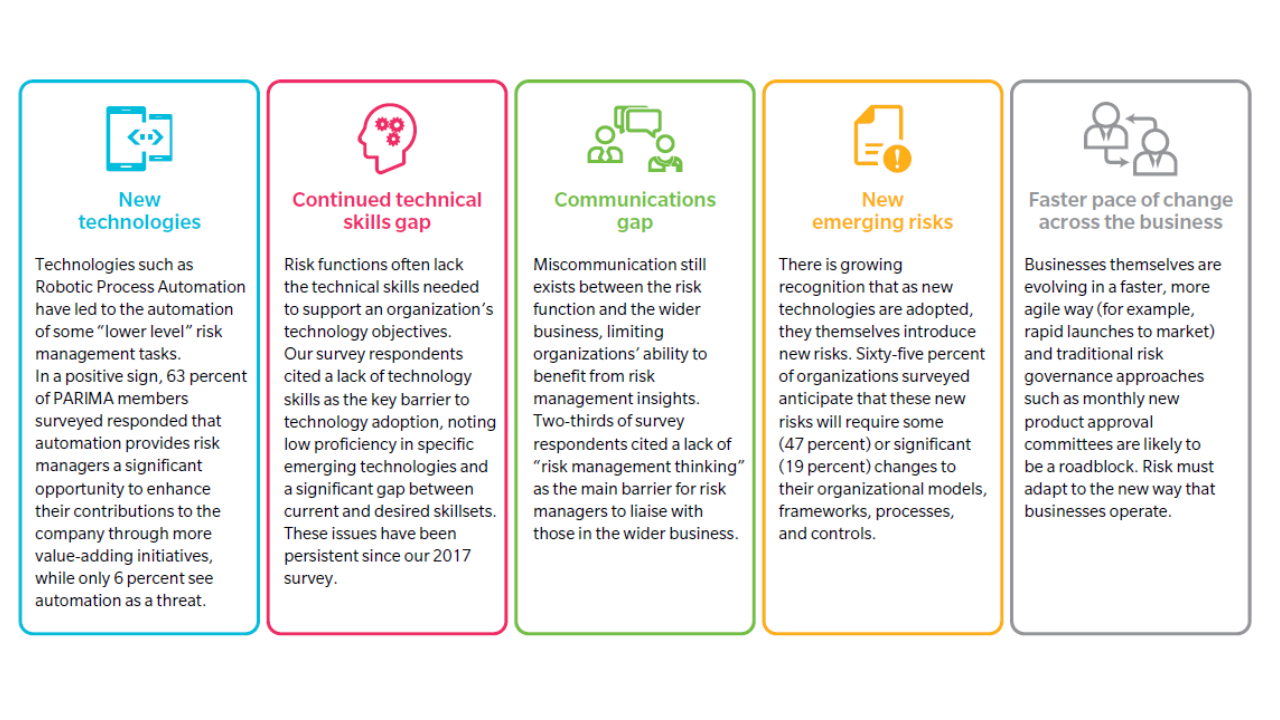

Amidst a changing risk landscape and increasing availability of technological tools that enable risk managers to do more, there is both a need and an opportunity to move toward that broader risk manager role. This need for change – not only in the risk manager’s role, but also in the broader approach to organizational risk management and technological change – is driven by five factors.

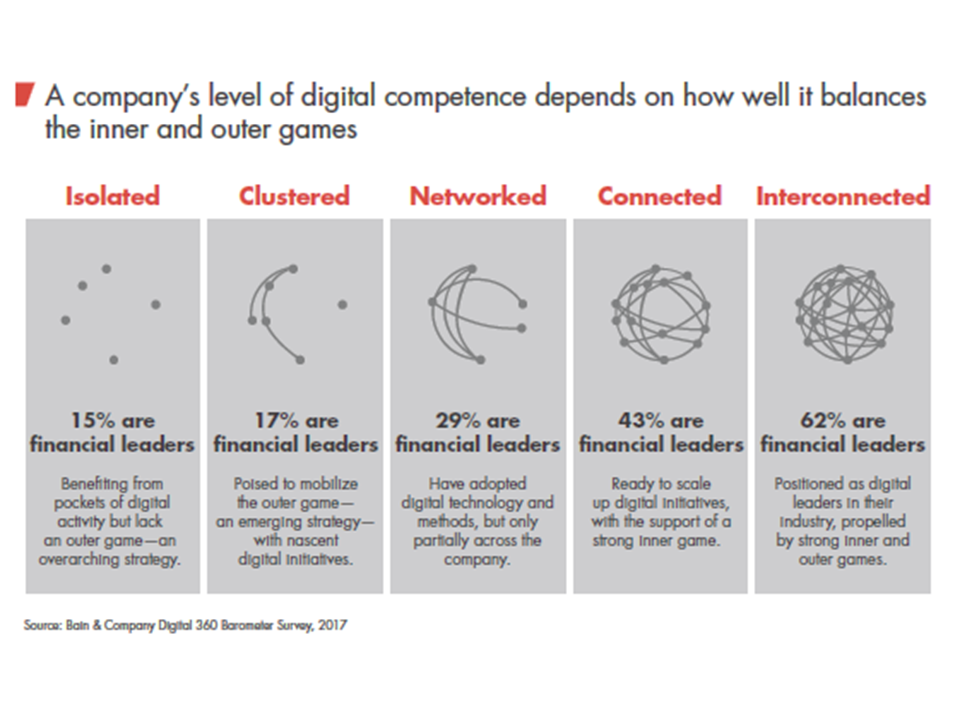

The rapid pace of change has many C-suite members questioning what will happen to their business models. Research shows that 73 percent of executives predict significant industry disruption in the next three years (up from 26 percent in 2018). In this challenging environment, risk managers have a great opportunity to demonstrate their relevance.

USING NEW TOOLS TO MANAGE RISKS

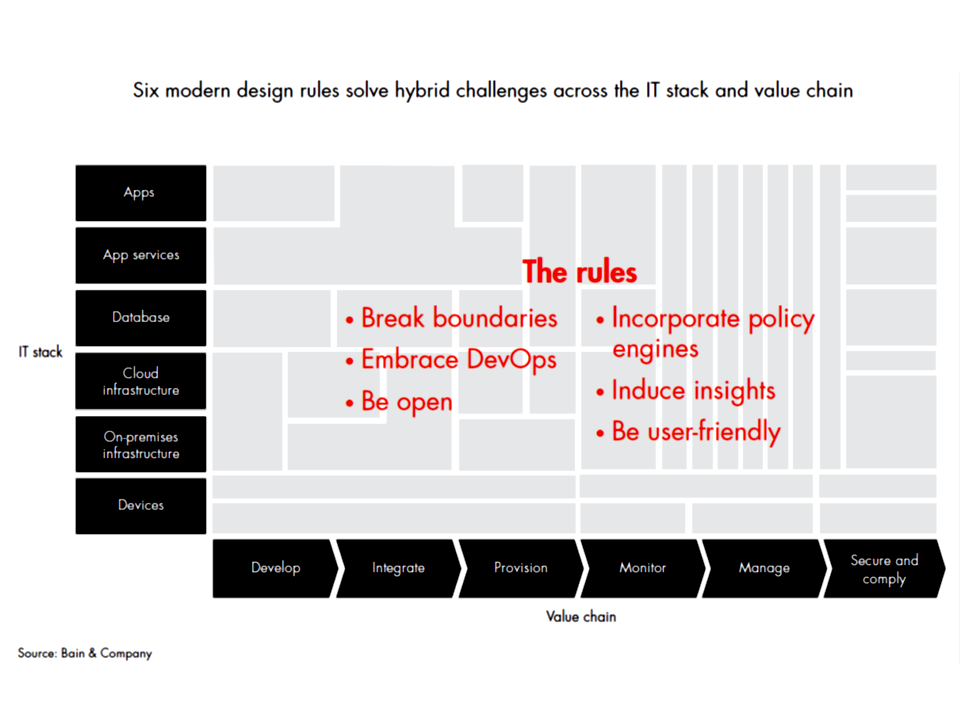

Emerging technologies present compelling opportunities for the field of risk management. As discussed in our 2017 report, the three levers of data, analytics, and processes allow risk professionals a framework to consider technology initiatives and their potential gains. Emerging tools can support risk managers in delivering a more dynamic, in-depth view of risks in addition to potential cost-savings.

However, this year’s survey shows that across Asia-Pacific, risk managers still feel they are severely lacking knowledge of emerging technologies across the business. Confidence scores were low in all but one category, risk management information systems (RMIS). These scores were only marginally higher for respondents in highly regulated industries (financial services and energy utilities), underscoring the need for further training across all industries.

When it comes to technology, risk managers should aim for “digital fluency”, a level of familiarity that allows them to

- first determine how technologies can help address different risk areas,

- and then understand the implications of doing so.

They need not understand the inner workings of various technologies, as their niche should remain aligned with their core expertise: applying risk technical skills, principles, and practices.

CULTIVATING A “DIGITAL-FIRST” MIND-SET

Successful technology adoption does not only present a technical skills challenge. If risk function digitalization is to be effective, risk managers must champion a cultural shift to a “digital-first” mindset across the organization, where all stakeholders develop a habit of thinking about how technology can be used for organizational benefit.

For example, the risk manager of the future will be looking to glean greater insights using increasingly advanced analytics capabilities. To do this, they will need to actively encourage their organization

- to collect more data,

- to use their data more effectively,

- and to conduct more accurate and comprehensive analyses.

Underlying the risk manager’s digitalfirst mind-set will be three supporting mentalities:

1. The first of these is the perception of technology as an opportunity rather than a threat. Some understandable anxiety exists on this topic, since technology vendors often portray technology as a means of eliminating human input and labor. This framing neglects the gains in effectiveness and efficiency that allow risk managers to improve their judgment and decision making, and spend their time on more value-adding activities. In addition, the success of digital risk transformations will depend on the risk professionals who understand the tasks being digitalized; these professionals will need to be brought into the design and implementation process right from the start. After all, as the Japanese saying goes, “it is workers who give wisdom to the machines.” Fortunately, 87 percent of PARIMA surveyed members indicated that automating parts of the risk manager’s job to allow greater efficiency represents an opportunity for the risk function. Furthermore, 63 percent of respondents indicated that this was not merely a small opportunity, but a significant one (Exhibit 6). This positive outlook makes an even stronger statement than findings from an earlier global study in which 72 percent of employees said they see technology as a benefit to their work

2. The second supporting mentality will be a habit of looking for ways in which technology can be used for benefit across the organization, not just within the risk function but also in business processes and client solutions. Concretely, the risk manager can embody this culture by adopting a data-driven approach, whereby they consider:

- How existing organizational data sources can be better leveraged for risk management

- How new data sources – both internal and external – can be explored

- How data accuracy and completeness can be improved

“Risk managers can also benefit from considering outside-the-box use cases, as well as keeping up with the technologies used by competitors,” adds Keith Xia, Chief Risk Officer of OneHealth Healthcare in China.

This is an illustrative rather than comprehensive list, as a data-driven approach – and more broadly, a digital mind-set – is fundamentally about a new way of thinking. If risk managers can grow accustomed to reflecting on technologies’ potential applications, they will be able to pre-emptively spot opportunities, as well as identify and resolve issues such as data gaps.

3. All of this will be complemented by a third mentality: the willingness to accept change, experiment, and learn, such as in testing new data collection and analysis methods. Propelled by cultural transformation and shifting mind-sets, risk managers will need to learn to feel comfortable with – and ultimately be in the driver’s seat for – the trial, error, and adjustment that accompanies digitalization.

MANAGING THE NEW RISKS FROM EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

The same technological developments and tools that are enabling organizations to transform and advance are also introducing their own set of potential threats.

Our survey shows the PARIMA community is aware of this dynamic, with 96 percent of surveyed members expecting that emerging technologies will introduce some – if not substantial – new risks in the next five years.

The following exhibit gives a further breakdown of views from this 96 percent of respondents, and the perceived sufficiency of their existing frameworks. These risks are evolving in an environment where there are already questions about the relevance and sufficiency of risk identification frameworks. Risk management has become more challenging due to the added complexity from rapid shifts in technology, and individual teams are using risk taxonomies with inconsistent methodologies, which further highlight the challenges that risk managers face in managing their responses to new risk types.

To assess how new technology in any part of the organization might introduce new risks, consider the following checklist :

HIGH-LEVEL RISK CHECKLIST FOR EMERGING TECHNOLOGY

- Does the use of this technology cut across existing risk types (for example, AI risk presents a composite of technology risk, cyber risk, information security risk, and so on depending on the use case and application)? If so, has my organization designated this risk as a new, distinct category of risk with a clear definition and risk appetite?

- Is use of this technology aligned to my company’s strategic ambitions and risk appetite ? Are the cost and ease of implementation feasible given my company’s circumstances?

- Can this technology’s implications be sufficiently explained and understood within my company (e.g. what systems would rely on it)? Would our use of this technology make sense to a customer?

- Is there a clear view of how this technology will be supported and maintained internally, for example, with a digitally fluent workforce and designated second line owner for risks introduced by this technology (e.g. additional cyber risk)?

- Has my company considered the business continuity risks associated with this technology malfunctioning?

- Am I confident that there are minimal data quality or management risks? Do I have the high quality, large-scale data necessary for advanced analytics? Would customers perceive use of their data as reasonable, and will this data remain private, complete, and safe from cyberattacks?

- Am I aware of any potential knock-on effects or reputational risks – for example, through exposure to third (and fourth) parties that may not act in adherence to my values, or through invasive uses of private customer information?

- Does my organization understand all implications for accounting, tax, and any other financial reporting obligations?

- Are there any additional compliance or regulatory implications of using this technology? Do I need to engage with regulators or seek expert advice?

- For financial services companies: Could I explain any algorithms in use to a customer, and would they perceive them to be fair? Am I confident that this technology will not violate sanctions or support crime (for example, fraud, money laundering, terrorism finance)?

SECURING A MORE TECHNOLOGY-CONVERSANT RISK WORKFORCE

As risk managers focus on digitalizing their function, it is important that organizations support this with an equally deliberate approach to their people strategy. This is for two reasons, as Kate Bravery, Global Solutions Leader, Career at Mercer, explains: “First, each technological leap requires an equivalent revolution in talent; and second, talent typically becomes more important following disruption.”

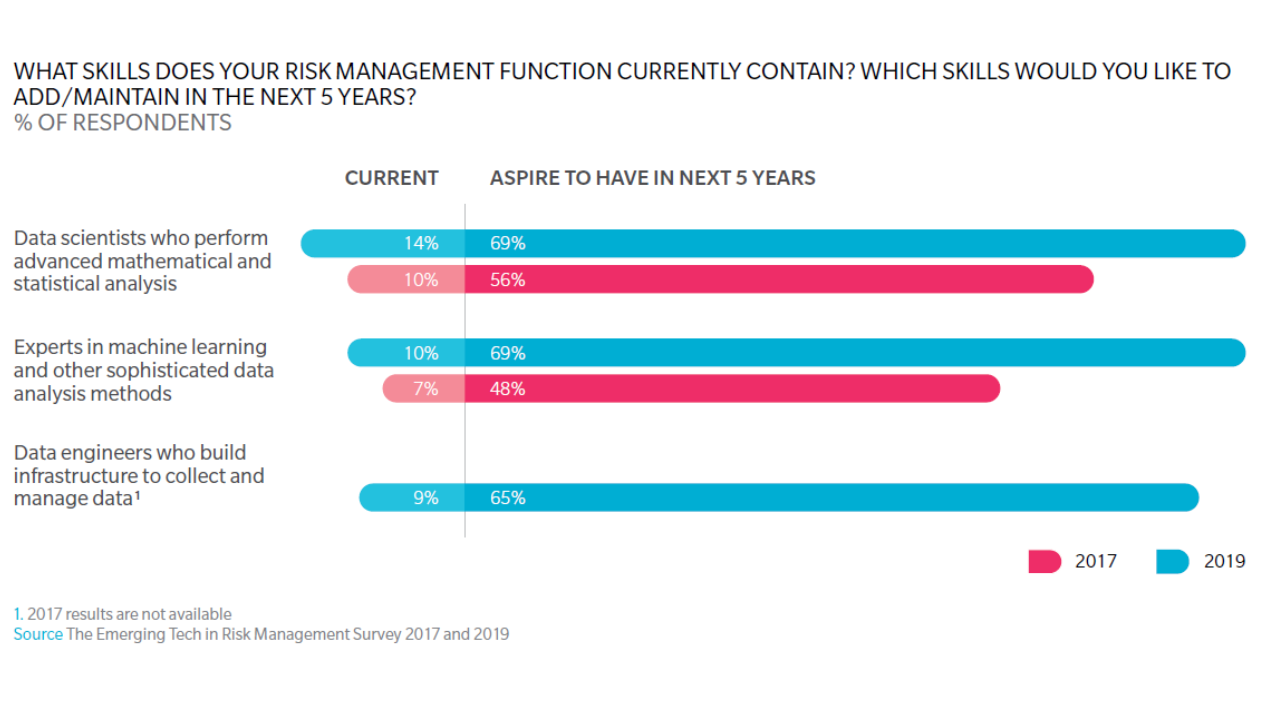

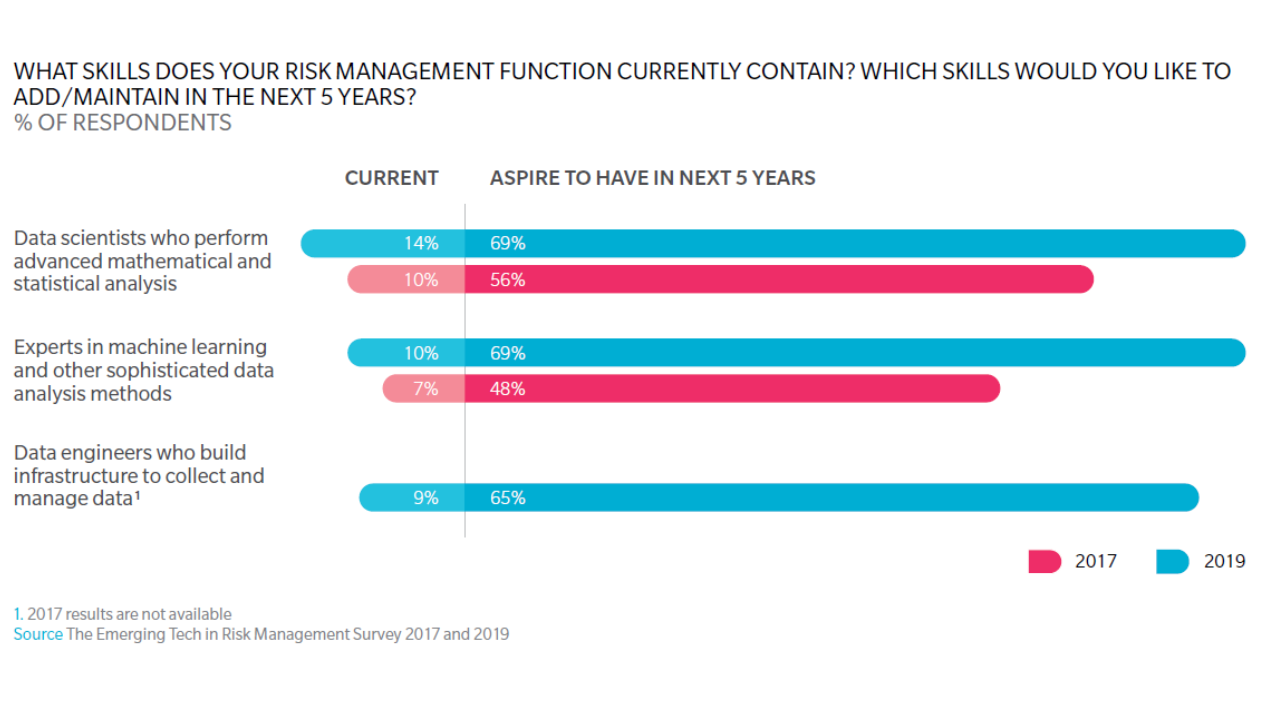

While upskilling the current workforce is a positive step, as addressed before, organizations must also consider a more holistic talent management approach. Risk managers understand this imperative, with survey respondents indicating a strong desire to increase technology expertise in their function within the next five years.

Yet, little progress has been made in adding these skills to the risk function, with a significant gap persisting between aspirations and the reality on the ground. In both 2017 and 2019 surveys, the number of risk managers hoping to recruit technology experts has been at least 4.5 times the number of teams currently possessing those skills.

EMBEDDING RISK CULTURE THROUGHOUT THE ORGANIZATION

Our survey found that a lack of risk management thinking in other parts of the organization is the biggest barrier the risk function faces in working with other business units. This is a crucial and somewhat alarming finding – but new technologies may be able to help.

As technology allows for increasingly accurate, relevant, and holistic risk measures, organizations should find it easier to develop risk-based KPIs and incentives that can help employees throughout the business incorporate a risk-aware approach into their daily activities.

From an organizational perspective, a first step would be to describe risk limits and risk tolerance in a language that all stakeholders can relate to, such as potential losses. Organizations can then cascade these firm-wide risk concepts down to operational business units, translating risk language into tangible and relevant incentives that encourages behavior that is consistent with firm values. Research shows that employees in Asia want this linkage, citing a desire to better align their individual goals with business goals.

The question thus becomes how risk processes can be made an easy, intuitive part of employee routines. It is also important to consider KPIs for the risk team itself as a way of encouraging desirable behavior and further embedding a risk-aware culture. Already a majority of surveyed PARIMA members use some form of KPIs in their teams (81 percent), and the fact that reporting performance is the most popular service level measure supports the expectation that PARIMA members actively keep their organization informed.

At the same time, these survey responses also raise a number of questions. Forty percent of organizations indicate that they measure reporting performance, but far fewer are measuring accuracy (15 percent) or timeliness (16 percent) of risk analytics – which are necessary to achieve improved reporting performance. Moreover, the most-utilized KPIs in this year’s survey tended to be tangible measures around cost, from which it can be difficult to distinguish a mature risk function from a lucky one.

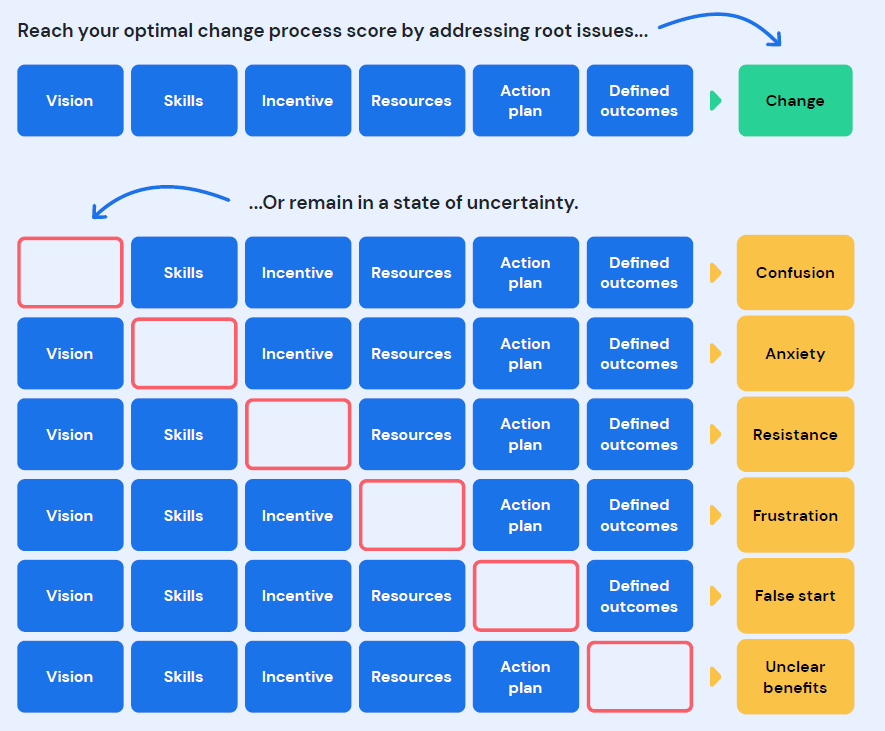

SUPPORTING TRANSFORMATIONAL CHANGE PROGRAMS

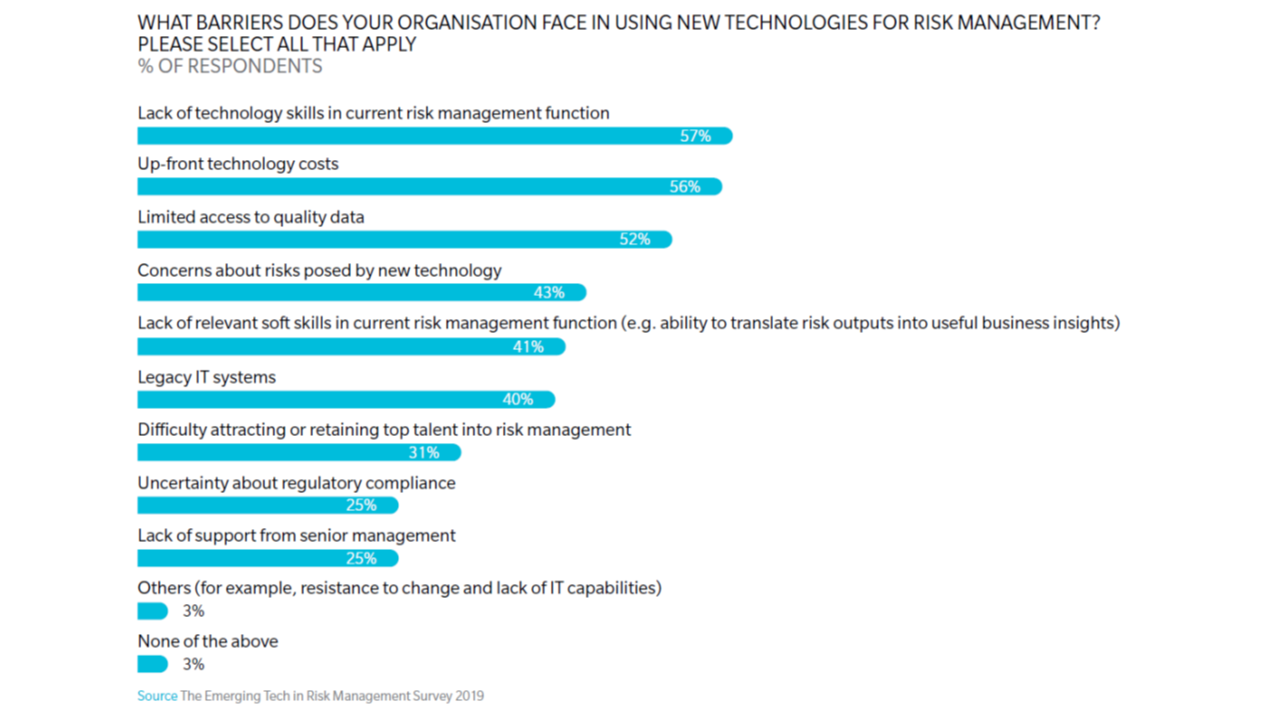

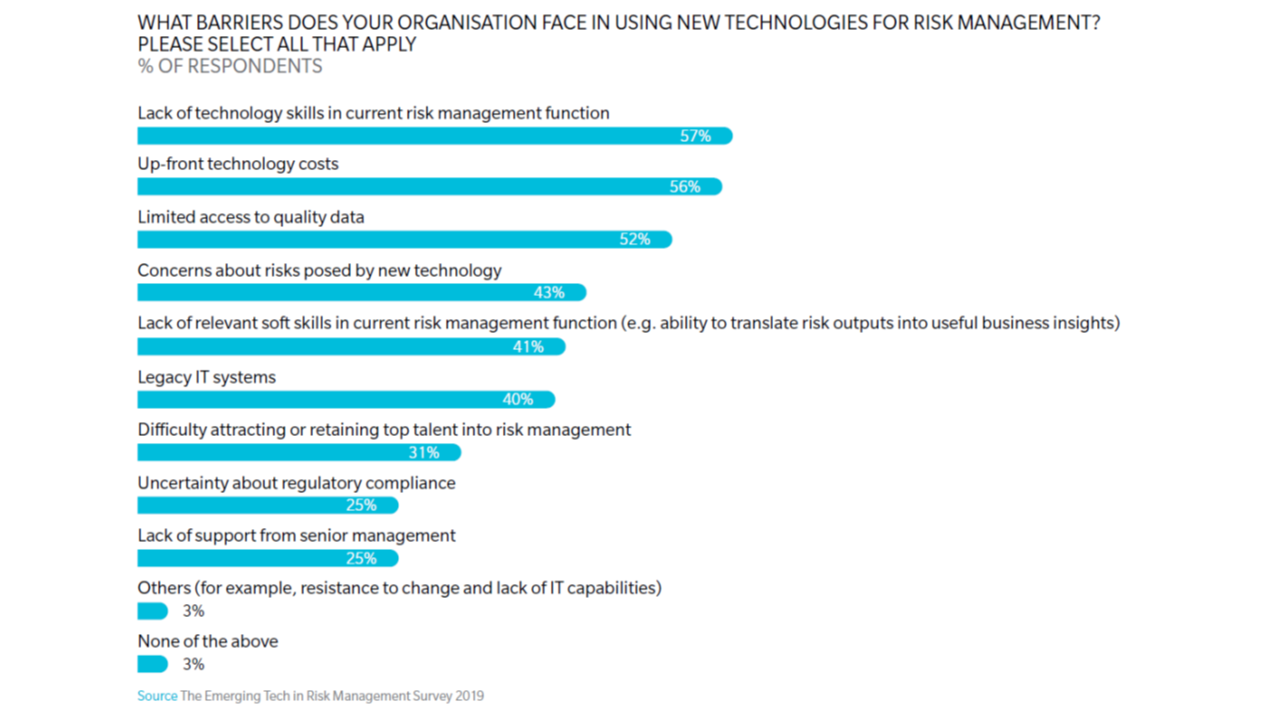

Even with a desire from individual risk managers to digitalize and complement organizational intentions, barriers still exist that can leave risk managers using basic tools. In 2017, cost and budgeting concerns were the single, standout barrier to risk function digitalization, chosen by 67 percent of respondents, well clear of second placed human capital concerns at 18 percent. This year’s survey responses were much closer, with a host of ongoing barriers, six of which were cited by more than 40 percent of respondents.

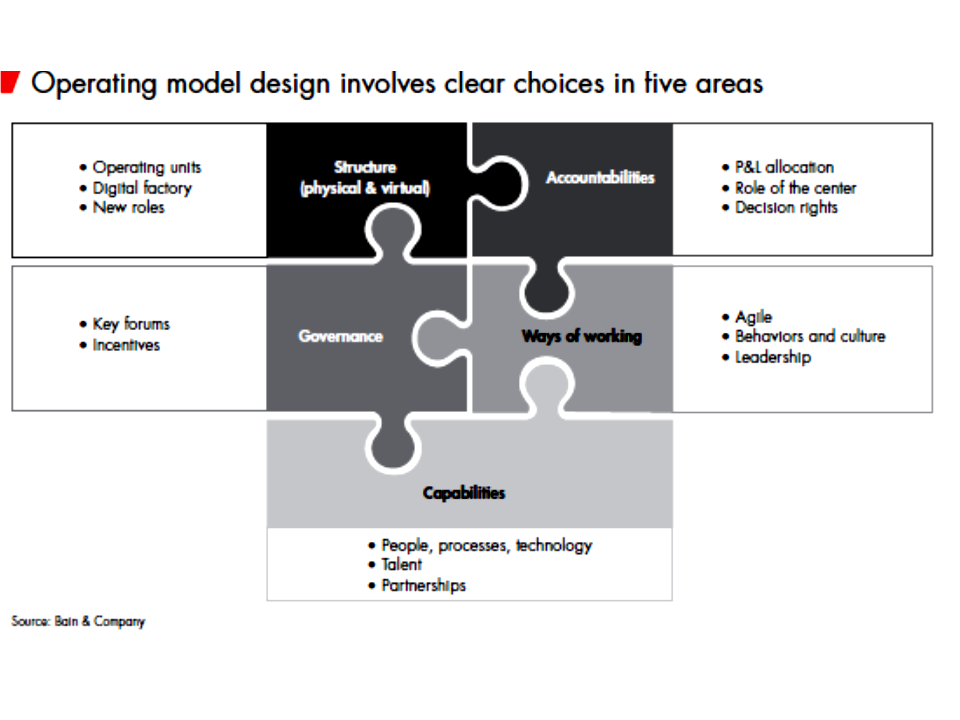

Implementing the nuts and bolts of digitalization will require a holistic transformation program to address all these barriers. That is not to say that initiatives must necessarily be massive in scale. In fact, well-designed initiatives targeting specific business problems can be a great way to demonstrate success that can then be replicated elsewhere to boost innovation.

Transformational change is inherently difficult, in particular where it spans both technological as well as people dimensions. Many large organizations have generally relied solely on IT teams for their “digital transformation” initiatives. This approach has had limited success, as such teams are usually designed to deliver very specific business functionalities, as opposed to leading change initiatives. If risk managers are to realize the benefits of such transformation, it is incumbent on them to take a more active role in influencing and leading transformation programs.

Click here to access Marsh’s and Parima’s detailed report