The main compliance challenges

We know that businesses and government entities alike struggle to manage compliance requirements. Many have put up with challenges for so long—often with limited resources—that they no longer see how problematic the situation has become.

FIVE COMPLIANCE CHALLENGES YOU MIGHT BE DEALING WITH

01 COMPLIANCE SILOS

It’s not uncommon that, over time, separate activities, roles, and teams develop to address different compliance requirements. There’s often a lack of integration and communication among these teams or individuals. The result is duplicated efforts—and the creation of multiple clumsy and inefficient systems. This is then perpetuated as compliance processes change in response to regulations, mergers and acquisitions, or other internal business re-structuring.

02 NO SINGLE VIEW OF COMPLIANCE ASSURANCE

Siloed compliance systems also make it hard for senior management to get an overview of current compliance activities and perform timely risk assessments. If you can’t get a clear view of compliance risks, then chances are good that a damaging risk will slip under the radar, go unaddressed, or simply be ignored.

03 COBBLED TOGETHER, HOME-GROWN SYSTEMS

Using generalized software, like Excel spreadsheets and Word documents, in addition to shared folders and file systems, might have made sense at one point. But, as requirements become more complex, these systems become more frustrating, inefficient, and risky. Compiling hundreds or thousands of spreadsheets to support compliance management and regulatory reporting is a logistical nightmare (not to mention time-consuming). Spreadsheets are also prone to error and limited because they don’t provide audit trails or activity logs.

04 OLD SOFTWARE, NOT DESIGNED TO KEEP UP WITH FREQUENT CHANGES

You could be struggling with older compliance software products that aren’t designed to deal with constant change. These can be increasingly expensive to upgrade, not the most user-friendly, and difficult to maintain.

05 NOT USING AUTOMATED MONITORING

Many compliance teams are losing out by not using analytics and data automation. Instead, they rely heavily on sample testing to determine if compliance controls and processes are working, so huge amounts of activity data is never actually checked.

Transform your compliance management process

Good news! There’s some practical steps you can take to transform compliance processes and systems so that they become way more efficient and far less expensive and painful.

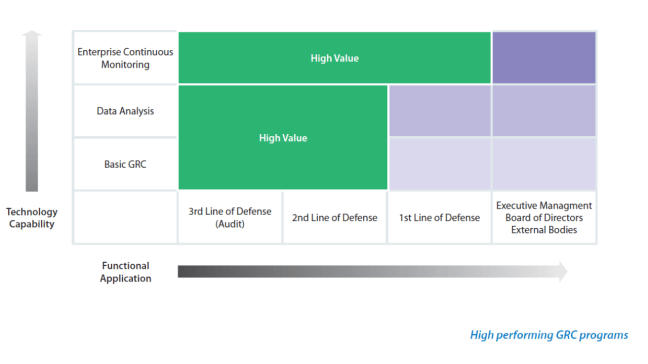

It’s all about optimizing the interactions of people, processes, and technology around regulatory compliance requirements across the entire organization.

It might not sound simple, but it’s what needs to be done. And, in our experience, it can be achieved without becoming massively time-consuming and expensive. Technology for regulatory compliance management has evolved to unite processes and roles across all aspects of compliance throughout your organization.

Look, for example, at how technology like Salesforce (a cloud-based system with big data analytics) has transformed sales, marketing, and customer service. Now, there’s similar technology which brings together different business units around regulatory compliance to improve processes and collaboration for the better.

Where to start?

Let’s look at what’s involved in establishing a technology-driven compliance management process. One that’s driven by data and fully integrated across your organization.

THE BEST PLACE TO START IS THE END

Step 1: Think about the desired end-state.

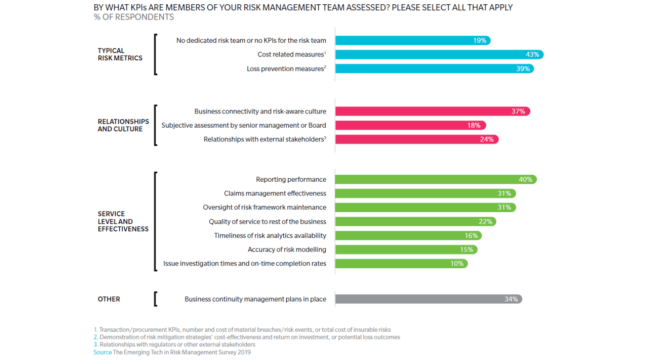

First, consider the objectives and the most important outcomes of your new process. How will it impact the different stakeholders? Take the time to clearly define the metrics you’ll use to measure your progress and success.

A few desired outcomes:

- Accurately measure and manage the costs of regulatory and policy compliance.

- Track how risks are trending over time, by regulation, and by region.

- Understand, at any point in time, the effectiveness of compliance-related controls.

- Standardize approaches and systems for managing compliance requirements and risks across the organization.

- Efficiently integrate reporting on compliance activities with those of other risk management functions.

- Create a quantified view of the risks faced due to regulatory compliance failures for executive management.

- Increase confidence and response times around changing and new regulations.

- Reduce duplication of efforts and maximize overall efficiency.

NOW, WHAT DO YOU NEED TO SUPPORT YOUR OBJECTIVES?

Step 2: Identify the activities and capabilities that will get you the desired outcomes.

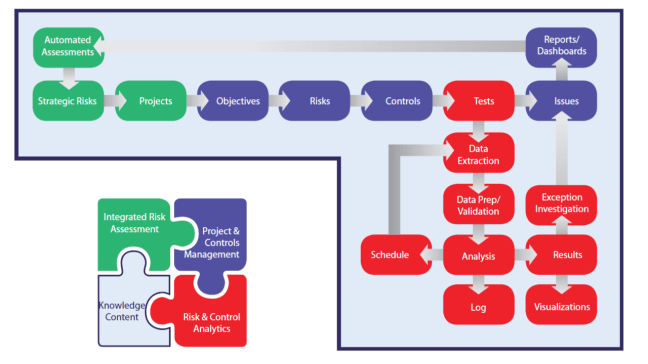

Consider the different parts of the compliance management process below. Then identify the steps you’ll need to take or the changes you’ll need to make to your current activity that will help you achieve your objectives. We’ve put together a cheat sheet to help this along.

IDENTIFY & IMPLEMENT COMPLIANCE CONTROL PROCEDURES

- 01 Maintain a central library of regulatory requirements and internal corporate policies, allocated to owners and managers.

- 02 Define control processes and procedures that will ensure compliance with regulations and policies.

- 03 Link control processes to the corresponding regulations and corporate policies.

- 04 Assess the risk of control weaknesses and failure to comply with regulations and policies.

RUN TRANSACTIONAL MONITORING ANALYTICS

- 05 Monitor the effectiveness of controls and compliance activities with data analytics.

- 06 Get up-to-date confirmation of the effectiveness of controls and compliance from owners with automated questionnaires or certification of adherence statements.

MANAGE RESULTS & RESPOND

- 07 Manage the entire process of exceptions generated from analytic monitoring and from the generation of questionnaires and certifications.

REPORT RESULTS & UPDATE ASSESSMENTS

- 08 Use the results of monitoring and exception management to produce risk assessments and trends.

- 09 Identify new and changing regulations as they occur and update repositories and control and compliance procedures.

- 10 Report on the current status of compliance management activities from high- to low-detail levels.

IMPROVE THE PROCESS

- 11 Identify duplicate processes and fix procedures to combine and improve controls and compliance tests.

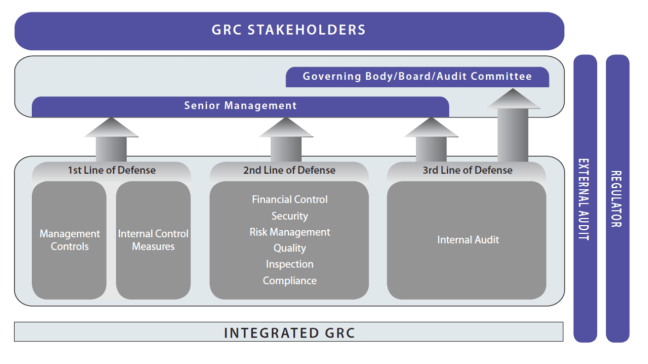

- 12 Integrate regulatory compliance risk management, monitoring, and reporting with overall risk management activities.

Eight compliance processes in desperate need of technology

01 Centralize regulations & compliance requirements

A major part of regulatory compliance management is staying on top of countless regulations and all their details. A solid content repository includes not only the regulations themselves, but also related data. By centralizing your regulations and compliance requirements, you’ll be able to start classifying them, so you can eventually search regulations and requirements by type, region of applicability, effective dates, and modification dates.

02 Map to risks, policies, & controls

Classifying regulatory requirements is no good on its own. They need to be connected to risk management, control and compliance processes, and system functionality. This is the most critical part of a compliance management system.

Typically, in order to do this mapping, you need:

- An assessment of non-compliant risks for each requirement.

- Defined processes for how each requirement is met.

- Defined controls that make sure the compliance process is effective in reducing non-compliance risks.

- Controls mapped to specific analytics monitoring tests that confirm the effectiveness on an ongoing basis.

- Assigned owners for each mapped requirement. Specific processes and controls may be assigned to sub-owners.

03 Connect to data & use advanced analytics

Using different automated tests to access and analyze data is foundational to a data-driven compliance management approach.

The range of data sources and data types needed to perform compliance monitoring can be humongous. When it comes to areas like FCPA or other anti-bribery and corruption regulations, you might need to access entire populations of purchase and payment transactions, general ledger entries, payroll, and travel and entertainment expenses. And that’s just the internal sources. External sources could include things like the Politically Exposed Persons database or Sanctions Checks.

Extensive suites of tests and analyses can be run against the data to determine whether compliance controls are working effectively and if there are any indications of transactions or activities that fail to comply with regulations. The results of these analyses identify specific anomalies and control exceptions, as well as provide statistical data and trend reports that indicate changes in compliance risk levels.

Truly delivering on this step involves using the right technology since the requirements for accessing and analyzing data for compliance are demanding. Generalized analytic software is seldom able to provide more than basic capabilities, which are far removed from the functionality of specialized risk and control monitoring technologies.

04 Monitor incidents & manage issues

It’s important to quickly and efficiently manage instances once they’re flagged. But systems that create huge amounts of “false positives” or “false negatives” can end up wasting a lot of time and resources. On the other hand, a system that fails to detect high risk activities creates risk of major financial and reputational damage. The monitoring technology you choose should let you fine-tune analytics to flag actual risks and compliance failures and minimize false alarms.

The system should also allow for an issues resolution process that’s timely and maintains the integrity of responses. If the people responsible for resolving a flagged issue don’t do it adequately, an automated workflow should escalate the issues to the next level.

Older software can’t meet the huge range of incident monitoring and issues management requirements. Or it can require a lot of effort and expense to modify the procedures when needed.

05 Manage investigations

As exceptions and incidents are identified, some turn into issues that need in-depth investigation. Software helps this investigation process by allowing the user to document and log activities. It should also support easy collaboration of anyone involved in the investigation process.

Effective security must be in place around access to all aspects of a compliance management system. But it’s extra important to have a high level of security and privacy for the investigation management process.

06 Use surveys, questionnaires & certifications

Going beyond just transactional analysis and monitoring, it’s also important to understand what’s actually happening right now, by collecting the input of those working in the front-lines.

Software that has built-in automated surveys and questionnaires can gather large amounts of current information directly from these individuals in different compliance roles, then quickly interpret the responses.

For example, if you’re required to comply with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), you can use automated questionnaires and certifications to collect individual sign-off on SOX control effectiveness questions. That information is consolidated and used to support the SOX certification process far more efficiently than using traditional ways of collecting sign-off.

07 Manage regulatory changes

Regulations change constantly, and to remain compliant, you need to know—quickly— when those changes happen. This is because changes can often mean modifications to your established procedures or controls, and that could impact your entire compliance management process.

A good compliance software system is built to withstand these revisions. It allows for easy updates to existing definitions of controls, processes, and monitoring activities.

Before software, any regulatory changes would involve huge amounts of manual activities, causing backlogs and delays. Now much (if not most) of the regulatory change process can be automated, freeing your time to manage your part of the overall compliance program.

08 Ensure regulatory examination & oversight

No one likes going through compliance reviews by regulatory bodies. It’s even worse if failures or weaknesses surface during the examination.

But if that happens to you, it’s good to know that many regulatory authorities have proven to be more accommodating and (dare we say) lenient when your compliance process is strategic, deliberate, and well designed.

There are huge benefits, in terms of efficiency and cost savings, by using a structured and well-managed regulatory compliance system. But the greatest economic benefit happens when you can avoid a potentially major financial penalty as a result of replacing an inherently unreliable and complicated legacy system with one that’s purpose-built and data-driven.