SITUATION OVERVIEW

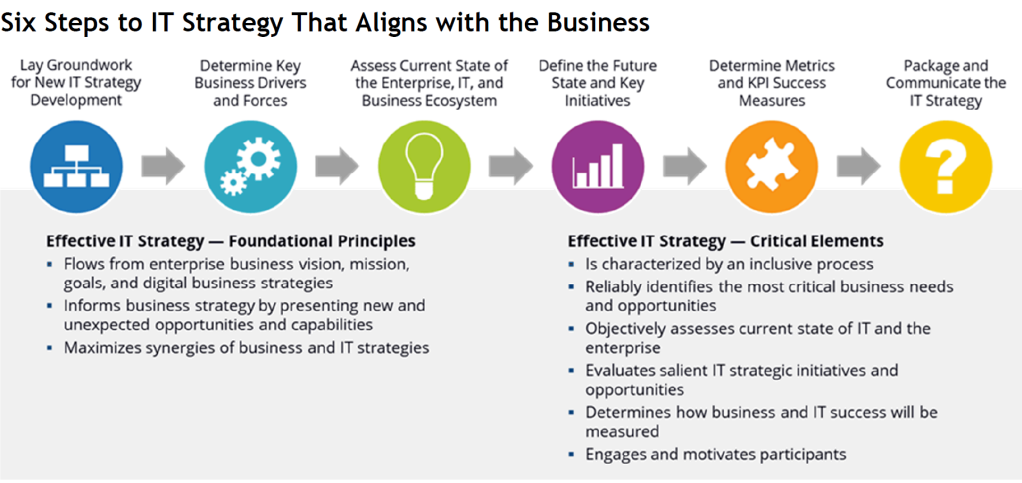

Aligning IT strategies with business strategies has been a mantra for CIOs for quite a few years. Yet, despite the apparent straightforward nature of the endeavor, many CIOs struggle to achieve that alignment. The rapid rise of digital technologies and transformation has significantly raised the bar — now, CIOs must find synergies and multiplier effects, not just business alignment, and that has a big impact on the creation of IT strategies.

IT strategy logically flows from the enterprise business vision, mission, goals, and strategies — especially digital business strategies. Collectively, they should anchor and guide IT strategy development. Yet IT strategy should also inform business strategy by presenting new and unexpected opportunities and capabilities. CIOs and strategy development stakeholders must cycle back and forth between business and IT strategies to maximize synergies.

CIOs need to find new process-driven approaches to formulating strategy in the new world where technology is found in every aspect of the business. An effective strategy development process is inclusive of all stakeholders,

reliably identifies the most critical business needs and opportunities,

objectively assesses the current state of IT and the enterprise,

surfaces and vets all salient IT strategic initiatives and opportunities,

explains how business and IT success will be measured,

and engages and motivates all those who must embrace, support, and execute the strategy.

This study lays out a process for creating IT strategy. It explains how CIOs can envision and develop new IT strategies, identifies key activities and actions for each step, and provides advice on ensuring effectiveness and adoption of an IT strategy.

Stage 1: Lay Groundwork for New IT Strategy Development

Under the duress of executive pressure to transform IT, CIOs may be tempted to jump into formulating new IT strategies without laying the proper groundwork. Like IT itself, however, IT strategy development must extend beyond the boundaries of the IT organization as digital business concerns pervade all aspects of the business, its partners, and its customers. That means that a diverse set of organizations and stakeholders will necessarily be involved in creating new IT strategies. Taking the time to prepare and get all necessary stakeholders onboard, will, however, reduce friction and lead to a faster effort with better results. The groundwork stage is intended to set the stage for all subsequent strategy work.

Key Activities

- Identify, contact, and recruit all salient stakeholders. F. Edward Freeman’s work on the Stakeholder Theory lists employees, environmentalists, suppliers, governments, community organizations, owners, media, customers, and competitors. Additional stakeholders would include LOB executives, CIO direct reports, and key partner representatives. Team members must be willing and able to devote the necessary time for the duration of their involvement.

- Build trusting relationships among all stakeholders, and gain support for the strategy effort.

- Educate nontechnical stakeholders on essentials of digital technologies and digital business and operating models.

- Conduct workshops to learn about and select key tools and practices, such as agile, design thinking, value streams, and lean start-up, that can help create a structured framework.

- Agree on a strategy development process and governance and oversight for the process.

- Define the purpose and desired outcomes for the IT strategy development process.

- Review existing IT and enterprise vision, mission, strategy, and goals.

- Review IT spend across the entire enterprise.

- Create/adopt an agile approach to formulating the IT strategy.

One of the biggest mistakes CIOs can make in formulating an IT strategy is to use ad hoc, nonsystematic approaches that attempt to match technology solutions with highly visible problems.

Modern IT strategies are complex, have multitudes of interdependencies and diverse and powerful stakeholders, and have a material impact on the success or failure of the business. Strategy development is one of the most critical responsibilities — one that requires rigor and a structured approach and processes.

Above all, the IT strategy formulation process needs to be agile, as business environments are continually shifting. A strategy that only adjusts on an annual basis runs the risk at any point in time of being mistargeted. The process needs to continually sense changes in the business ecosystem and prompt decisions about possible changes to the strategy.

Stage 2: Determine Key Business Drivers and Forces

IT strategies are intended to move businesses forward by

- creating new products and services,

- attracting and retaining customers,

- entering new markets,

- and solving business problems.

In that context, key issues and business drivers are those that constrain the business from moving forward or present opportunities to grow and succeed.

Business and IT strategies exist in a messy world of shifting business, social, technological, economic, and geopolitical forces. Those forces and dynamics make up the business context in which the IT strategy must function and succeed and form the basis for identifying key drivers that will shape and help decide what key initiatives need to be prioritized.

Key drivers are quite individualized to a given business. But they can include

- technology emergence and evolution;

- global competition and challenges;

- competition in the form of new business and/or operating models;

- shifting customer and market dynamics — personal, social, and cultural;

- geopolitical and regulatory shifts and uncertainties;

- environmental and climate impacts;

- and threats to privacy and security.

Key Activities

- Compile and review trends, disruptions, and forecasts in business, technology, environmental, geopolitical, social, regulatory, and other salient arenas.

- Identify the most important forces and drivers that will impact the enterprise and IT.

- Describe how the selected drivers will help define the desired future state of the enterprise.

- Prioritize and map drivers to time frames in which drivers are expected to be active.

- Describe responses that will be needed from the enterprise and IT.

- Time phase responses based on projected time frames.

While there may be a multitude of key issues, CIOs need to work with business leaders to select only those that truly move the needle for the business. It’s been said that, when everything is a priority, nothing is a priority and that is true when it comes to IT strategy. IT and LOB executives will have to subordinate the agendas of their own organizations to focus on the drivers that offer the most potential for business benefit to the enterprise. Selecting the most important drivers is critical, as the selected set will define the focus of successive stages of strategy development and the strategy itself.

Stage 3: Assess Current State of the Enterprise, IT, and Business Ecosystem

This stage requires an objective assessment of the IT organization, the enterprise, and its ecosystem for attributes and characteristics that could positively or negatively impact the formulation and execution of IT strategies. IT and LOB executives need to have frank discussions about « the good, the bad, and the ugly » aspects of IT and the enterprise. Business leaders can ill afford to launch into implementing strategies that their organizations, markets, and customers are not ready for. The following table provides key facets of IT, enterprises, and ecosystems that should be assessed.

Note that some of the attributes are more germane and important to the IT strategy and others are less so — the goal is not an exhaustive assessment but one that captures the current states that are most important to strategy development. The current state assessment is critical as it is the basis for identifying work that’s needed to reach the desired future state. A flawed or incomplete assessment will result in missed opportunities, failed initiatives, and potential derailment of IT transformation.

Key Activities

- Assemble necessary data, market and customer intelligence, and ecosystem intelligence to underpin analysis and decision making.

- Identify the most salient and important attributes for assessment.

- Create an assessment framework and scoring system.

- Describe the current states of the business and IT, using SWOT or other frameworks to assess relative competitiveness and readiness to execute business and IT strategies.

- Assess the viability and currency of the existing business strategy.

The current state assessment requires at least a basic framework that identifies the most salient attributes to keep stakeholders from getting too far down in the weeds. The intent is not to put every aspect of IT and the business under a microscope but instead to select attributes of both organizations that need to be addressed by the IT strategy. In support of that aim, the assessment should include a simple scoring system to measure importance (high, medium, low) of each selected attribute and the relative current state (strength, weakness, neutral). And the current state assessment should reflect the viewpoints of employees, managers, customers, partners, and the business’ ecosystem.

Step 4: Define the Future State and Key Initiatives

This stage focuses on defining what IT and the enterprise need to look like in the future over one-, two and three-year time frames and the strategic initiatives that will help IT assist the business in achieving that state. In describing the future state and initiatives, it’s critical to find the balance between pragmatic business problem-solving and innovative, aspirational efforts that will engage and motivate stakeholders.

As we noted previously, an agile approach that emphasizes learning and refinement in an iterative staged approach will create more adaptive strategies. Design thinking is another discipline that helps the strategy team frame (or reframe) problems and their solutions from the customers’ perspective to make sure that a prospective initiative and its outcome are important for the target audience. Finally, value streams can be used to help in understanding how a given strategy or initiative creates value and what components are necessary to construct the streams.

Collectively, the tools and practices should be employed in a series of workshops that distill the drivers, issues, and needs identified in the earlier stages of work into prioritized strategic initiatives comprising the IT strategy. Each workshop should focus on one initiative and involve only the stakeholders that are germane to that initiative.

In defining strategic initiatives, the strategy teams should start with a desired business outcome and initiative and then work through the value streams that produce that outcome. Supporting the value streams are IT capabilities:

- data,

- technology,

- talent,

- processes,

- and governance

necessary to deliver a given outcome. For example, a desired outcome or initiative focused on generating new revenue from appliance service data would require new IT capabilities (sub-initiatives) in data/analytics, product development, digital platforms, and new business model development.

Key Activities

- Distill drivers and issues into focused business problems, challenges, and opportunities.

- Create and run workshops to brainstorm initiatives and solutions that can address identified business drivers, problems, and needs. Start with divergent thinking to create a wide assortment of potential solutions, moving to convergent thinking to winnow down the solution set.

- Evaluate solutions based on constraints including budgets, financial viability, legacy culture and processes, talent availability, and other factors that may obviate some solutions.

- « Test » the top solution initiatives with those who will implement or be affected by the initiatives.

- Refine based on feedback or reexamine the original drivers and issues to ensure that they are relevant and important.

As powerful digital technologies have become core to business success, IT strategy development has become a « chicken and egg question »: technology or business — which comes first? The answer is « both. » Business needs, strategies, and models obviously drive technology strategies and adoption and will always be the dominant force in setting IT strategy at large enterprises. Yet, without cloud, data/analytics, and machine learning technologies, new business and operating models such as those employed by Uber, Lyft, Google, and others simply could not exist. Business strategies need to be the starting point and anchor for IT strategies, but at times, they will be shaped, if not driven, by new and emerging technologies.

Stage 5: Determine Metrics and KPI Success Measures

In the spirit of the old saying that « you can’t manage what you don’t measure, » this stage focuses on identifying key metrics and KPIs to measure the success (or lack thereof) of the IT strategy and specific strategic initiatives. Embedding top-level KPIs and metrics in the strategy is a means to ensure they become integral to the execution of the strategy — not an afterthought. It also helps ensure that the same stakeholders that define the strategy and initiatives identify the most meaningful metrics. And the metrics themselves are important to help fine-tune initiatives and target those that aren’t succeeding.

Key Activities

- Discuss how metrics and KPIs will be used and who will manage them.

- Discuss what strategy success looks like and whether there are thresholds of attainment.

- Start with desired business outcomes for each initiative, and identify key dimensions that measure performance.

- Identify metrics and KPIs that measure the outcomes in terms that will be useful to the CIO and LOB executives to fix problems or sunset initiatives that aren’t effective.

It’s important to favor outcome or impact measures (e.g., sales growth, process cost reduction) over activity measures (e.g., website visits, projects completed) as the former measure the health and the viability of IT and the business while the latter often turn into vanity metrics. Also important is creating metrics that help assess the success of IT strategy implementation and the business outcomes that result from execution.

Step 6: Package and Communicate the IT Strategy

Having formulated their IT strategy, it’s easy for CIOs and key stakeholders to think that the heavy lifting is done — all that’s left is to tell the rest of the company what the strategy is and then let the execution begin. Unfortunately, that is a surefire recipe for creating an IT strategy that is ignored, discounted, or unmoored. There are many possible reasons for nonsupport, including

- lack of understanding of the strategy and why it’s important,

- competing or conflicting interests and objectives on the part of executives,

- and failure to embrace and take ownership of execution.

Another simple reason is that the strategy lacks « stickiness » — it isn’t memorable and hence is quickly forgotten. Strategies can be made stickier by using themes to describe initiatives. Instead of « digitally transforming CX, » think « creating memorable customer moments, » or instead of « improving business intelligence capabilities, » think « uncovering insights that score business success. » Finally, IT strategy must be presented in the context of the enterprise business strategy and should clearly flow from and support that strategy.

Key Activities

- Identify all target audiences for the strategy and their top-level interests.

- Create a communication strategy and plan.

- Craft stories for each theme and initiative that tie IT initiatives to enterprise vision, mission, goals, and strategies.

- Clearly identify the roles each target audience will play — enactor, supporter, contributor, or beneficiary.

CIOs and strategy team members should create different versions of documents and presentations for each significant target audience. Viewers should feel like their unique interests and needs were considered and addressed in the formulation of strategies. Also important is to create stories that explain the strategy using « day in the life » or similar narratives instead of dry descriptive material.