Where to start on your ESG journey

Initiating your company’s commitment to reporting its environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics can prove a daunting task. But keep in mind: It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

“You don’t have to be perfect on Day 1, Your suppliers and stakeholders want to see progress.”

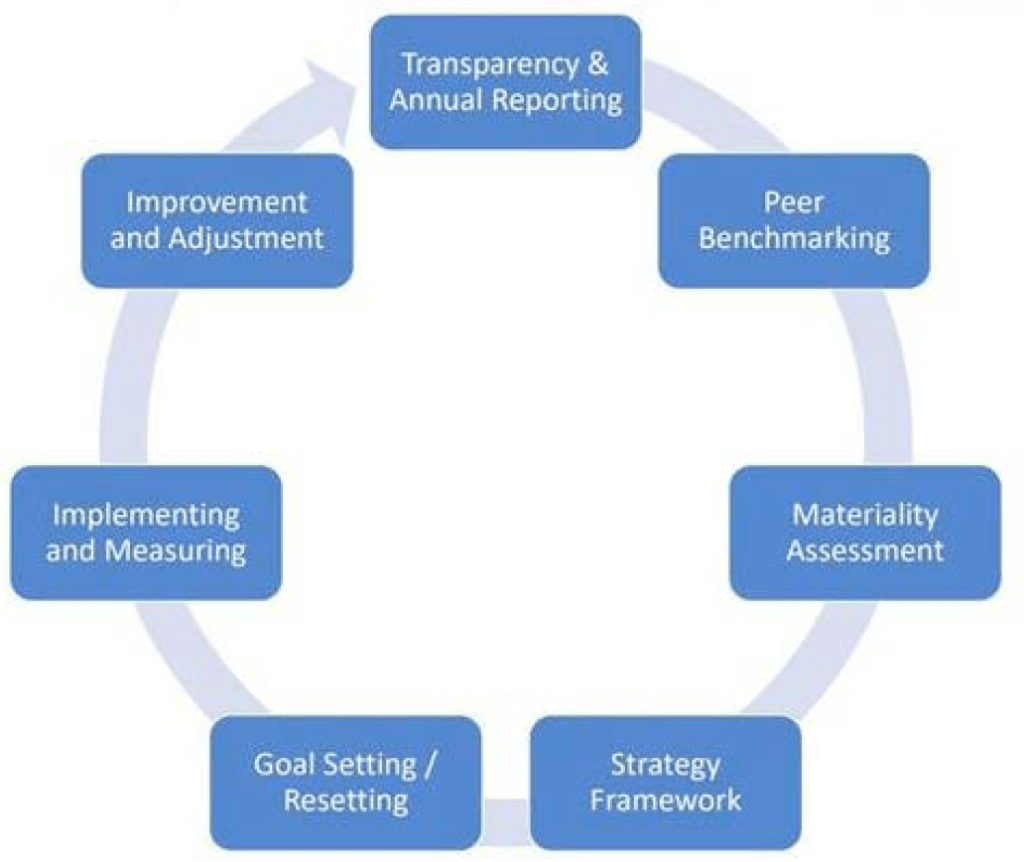

If your company is at this stage—perhaps bracing for the climate-related disclosure rule proposal put forward by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in March—a roadmap for getting your ESG efforts off the ground could look like this:

Transparency and annual reporting: “Start by identifying all the things your company is doing on ESG and build a baseline, that will give you an indication of how mature your program is today. Most likely you’re doing a lot already.”

Peer benchmarking: Where are your competitors in their ESG journeys? Have any of them experienced public success or failure you can learn from? From this exercise, your company can set realistic expectations of where it wants to be to keep pace with the competitive landscape.

Materiality assessment: “Understanding the materiality drivers for your industry or industries, depending on how your company is structured, is helpful”. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) offers a materiality map that provides guidance for 77 different industries. “Having something at the bottom doesn’t mean it’s not important and you stop doing it, but it helps you focus on the top tier, those are the items you need to set public goals on.” External materiality assessments also add credibility. »

Strategy framework: You know what your peers are doing, you know what’s important to the company and its investors— now is when you build out your strategy. “What does ESG mean for us?” “What are we trying to achieve?” ESG means different things for different companies, but “there’s also some fundamental truths about what ESG is and how and who ESG is serving—the stakeholders involved in your business.” Particularly for compliance professionals, serving shareholders is a natural strategic goal to build around.

Goal setting/resetting: During the peer benchmarking stage, you might note some of the milestones your competitors are striving toward. Their goals can help shape your own. “Do you want to be with the group where you’re just managing expectations, or do you want to compete or lead? It doesn’t happen overnight; you have to go through it step-by-step and build your goals for the long term to move the needle on this. If you’re setting carbon-neutral or net-zero deadlines, be realistic. “Put something out there that is achievable but not too easy”.

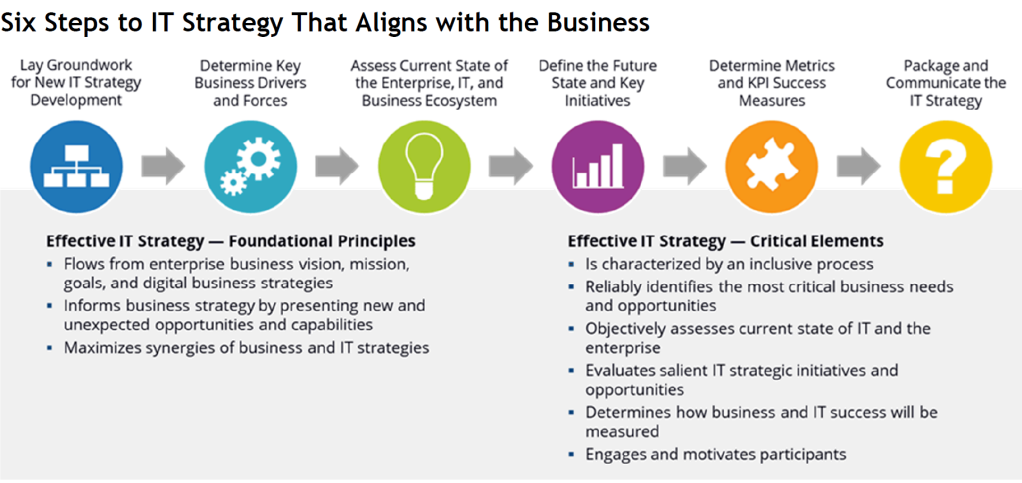

Implementing and measuring: This is the most important step because “it’s not in your hands anymore, You have to depend on your cross-functional teams … they will be the ones doing the work and implementing the initiatives.” Legal, human resources, operations, and other departments each have a part to play. You set up a dashboard to track how it was progressing on its key performance indicators on a quarterly basis. “We didn’t wait until the annual report to find out how we did”.

Improvement and adjustment: ESG reporting is a cycle, as evidenced by the arrow in the roadmap image. Going through these steps each year will help ensure a business is tailoring its objectives to continue to serve the most important piece of the puzzle. “This (ESG) is about the people, this is not about the processes, procedures, or requirements. It’s about the people—inspiring the people, collaborating cross-functionally, getting that momentum. That will help you move a lot faster.”

ESG: Adapting businesses should look beyond what is financially material

Environmental, as many would expect, covered climate-related elements, including carbon, energy, water, waste, and circularity. Diversity and inclusion, workplace safety, data privacy and protection, and customers and community fell under social. Governance claimed ethical business practices, board structure, disclosures and reporting, and executive compensation.

While ESG is comprised of just three words, it represents a lot more, encompassing many aspects of how businesses can operate efficiently, ethically, and more financially sound. “Sometimes you have to take out some of the buzzwords that cause people to lock in to certain thinking and open it up. One way to do that is to call it strategic nonfinancial materiality.”

It’s important to think of sustainability initiatives in terms of strategic nonfinancial materiality when it comes to the “tragedy of the commons,” a popular term in environmental science. “When we come across something we can use with no associated cost, we historically 100 percent of the time overuse and mismanage it. If something is common, we manage to mess it up.”

Examples of this include the atmosphere, oceans, and low earth orbit. Prudent corporations can innovate their thinking by getting ahead of an issue and “band[ing] together with industry [or] with other people who use those commons.” One way to think about this, is the term “double materiality,” which is often associated with the European Union’s Nonfinancial Reporting Directive. Double materiality calls for companies to consider their impact on society and the environment in addition to how sustainability issues affect the company.

“In the United States, we’re very well focused on financial materiality.” Also worth considering is “dynamic materiality,” a term utilized by the World Economic Forum that encourages companies to track certain factors year-over-year that might not be material now but could be in the future as the environment changes rapidly.

“These are dynamically material risks. You may still not know anything about them, but it is important to track them potentially as emerging risks, so, innovate how you look at not just what’s a snapshot material now but what are those things that are likely to be material soon.”

Regarding social, it’s suggested to contemplate news stories over the last few years that have changed how we deal with employees as an example. “They didn’t happen in a continuity, one day you weren’t talking about it, the next day it was on the front page and didn’t go off. Those are dynamically material things that drastically change, and you should be able to look for them.”

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) proposed climate-related disclosure rule released in March puts forward a similar process, asking companies “to report items that aren’t financially material but are risks nonetheless. This is new, and it’s going to affect the assurance functions,” including

- internal audit,

- enterprise risk management,

- and trade compliance.

“Assurance functions rely on governance and rules, and as we do this, we are going to expand that governance. When you do, you can expand assurance.”

Under the SEC’s proposal, assurance—first limited, then reasonable—is required for Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions disclosures outside of the financial statements for accelerated and large accelerated filers. There is no initial attestation requirement for Scope 3 disclosures, which are also subject to a safe harbor provision for affected registrants.

Regarding internal audit, “Maybe we can apply more automation [and] more data analytics to those areas. There is going to be more governance and rigor applied. Maybe more of our creative aspects and our more human and complex audits can go to other places because if greenhouse gas emissions are going to be extremely rigorized, similar to financials, maybe that can be a robotic process automation.”

Hidden Opportunities of Aligning Ethics and Compliance with ESG

ESG is rapidly evolving from grass-roots activism into a top down, board-driven mandate. It’s no mystery why, given that ESG assets make up a third of total global assets under management and are expected to surpass $50 trillion by 2025. ESG investing (also known as “impact investing”) was born of a growing awareness that long-term financial performance of businesses is inextricably intertwined with environmental, social, and governance factors. It has gained considerable traction as research suggests that companies with high ESG ratings tend to outperform their counterparts.

As a result, companies are moving beyond “check the box” ESG disclosures, to instead build out substantive ESG programs, identify appropriate quantitative and qualitative metrics to measure and validate their ESG initiatives, and distinguish themselves with “AAA” ESG ratings. Corporations are devoting significant capital, time, and resources to embedding environmental, social and governance factors into their business strategies and preparing annual ESG disclosures. Because ethics and compliance is so tightly woven into the social and governance elements of ESG, ethics and compliance officers are uniquely poised to support this broader effort in a number of ways.

THE OVERLAP BETWEEN E&C AND ESG

While ESG is strongly associated with environmental initiatives such as lowering carbon footprint, social and governance factors have achieved equal prominence. “Social” and “governance” define a company’s corporate citizen persona—or how it behaves—which is the heart and soul of ethics and compliance and, increasingly, a key factor in market valuation.

Ensuring a company behaves responsibly and ethically is both the mission of a Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer and the purpose of an ESG program. CECOs therefore have oversight of much of the infrastructure that supports social responsibility and prevents corruption, such as

- internal controls,

- Code of Conduct and policies,

- workplace health and safety,

- data protection and privacy,

- whistleblower hotlines, workforce training,

- and prevention of fraud, bribery and money laundering.

Ethics and compliance is mission critical because it is the reputational guardian of the company, the first line of defense against ethical fading. Thanks in large part to the lightning speed of today’s news cycle and the instantaneous impact of social media, corporate malfeasance scandals can have massive immediate impact on reputation and by extension valuation. It’s not unusual for news of bad corporate behavior to be accompanied by an immediate 20-30% drop in market cap. For a $3 billion company, that can equate to a one-day loss of $1 billion.

WHY SHOULD CECOS ALIGN WITH ESG?

It’s early days for ESG, relatively speaking, and best practices for building, quantifying, and disclosing ESG programs are rapidly evolving. As companies move towards transparency and begin walking the talk by aligning corporate culture to the stated ESG values, the historical function of E&C rolls up naturally to support these efforts. Opportunities abound for ethics and compliance leaders who join the challenge to improve their company’s ESG report card:

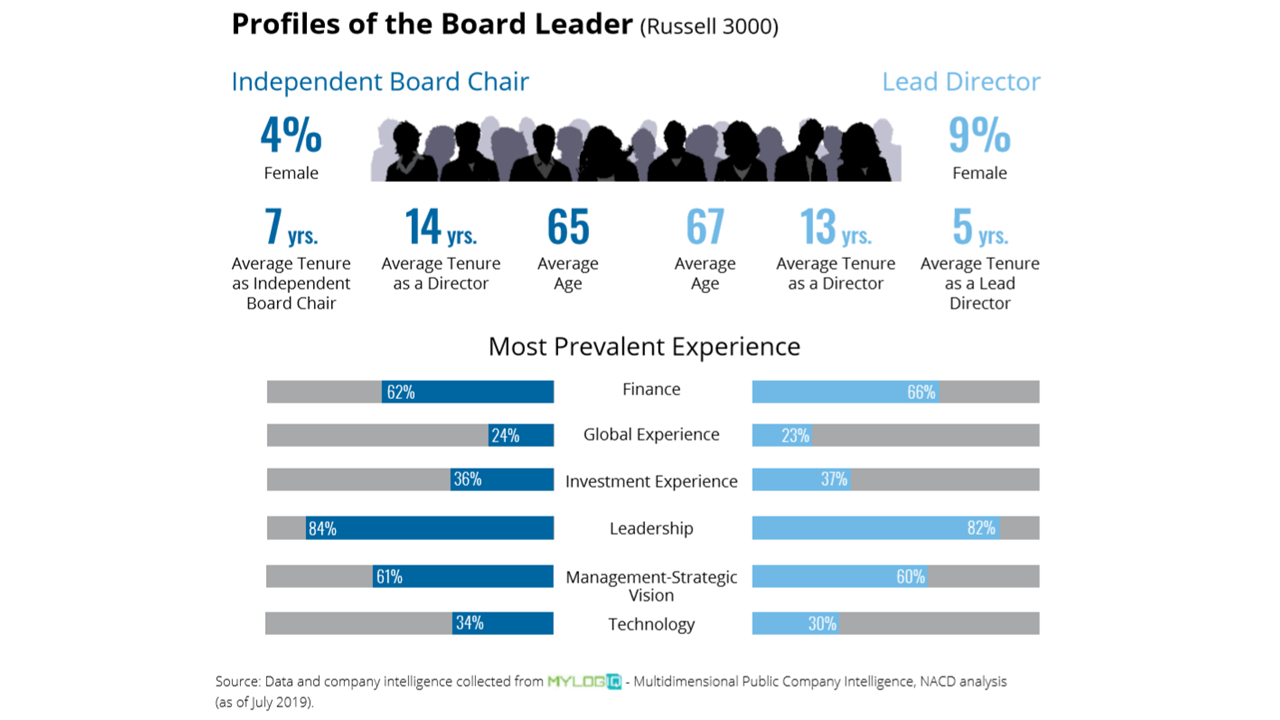

- Board visibility: Boards have come to recognize that robust ESG programs not only attract investors, but also offer a framework to mitigate business risk and future proof the company. Boards are now dedicating agenda time to embedding ESG into company strategy and risk mitigation. As a result, the head or coordinator of a company’s ESG program often reports to the board.

- More funding: A traditional ethics and compliance framework is often insufficient to meet the broader mandate of ESG. The top accounting and consulting firms are investing in building capability and capacity for ESG advisory services, and CECOs should be doing likewise internally. By tying ethics and compliance programming to ESG, E&C officers can tap into a bigger budget pool.

- Organizational clout: ESG planning and disclosure requires holistic engagement across the organization. By ensuring ethics and compliance is a strong complement of, and contributor to, the high-visibility high-value ESG initiative, CECOs can break organizational silos and increase the intrinsic value of ethics and compliance (and their roles) in the process.