Why Is Corporate Capitalism at a Tipping Point?

Stakeholders are beginning to pressure companies and investors to go beyond financial returns and take a more holistic view of their impact on society. This should not surprise us. After all, we have lived through two decades of hyper-transformation, during which rapidly evolving digital technologies, globalization, and massive investment flows have stressed and reshaped every aspect of business and society.

As in previous transformations, the winners created new dimensions of competition and built innovative business models that increased returns for shareholders. Many others found their businesses at risk of being disrupted, with familiar formulas no longer working. To meet the unwavering demands of Wall Street, many companies relentlessly optimized operating models, streamlined and concentrated supply chains, and specialized their assets and teams — leaving them less resilient and less adaptable to shifting markets and trade flows. The resulting waves of corporate restructuring, consolidation, and repositioning have fractured companies’ cultures and undermined their social contracts.

Furthermore, this hyper-transformation cascaded beyond individual companies and created socio-economic dynamics that left many people and communities economically disadvantaged and politically polarized. Combined with the increasing shared anxiety that the earth’s climate is changing faster than the planet can adapt, a global zeitgeist of risk and insecurity has emerged. We will enter the 2020s with more citizens, investors, and leaders convinced that the way business, capital, and government work must change — and change quickly.

We now must rethink the sustainability of the whole system in the face of extreme externalities — or risk losing social and political permission for further progress. The 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) identify the moral and existential threats that we must meet head-on. While some question the SDGs’ breadth and timeline, most agree that, if achieved, they would create a more just, inclusive, and sustainable world.

Goal 17 calls for new engagement by companies and capital in partnership for collective action across the public, social, and private sectors. Five years into the SDG agenda, there is ample evidence that governments, investors, and companies are beginning to exercise their capacity to create much-needed change.

Change Is Underway but Is Hardly Sufficient

Many institutional investors are racing to integrate ESG (environmental, social, and governance) assessments into their decision making, and they are expecting companies to report on how they deliver on those metrics. New efforts promote radical disclosure, like the Bloomberg/Carney TCFD (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures), which encourages signatories to report on the climate risks of their financial holdings.

New standards initiatives are creating a foundation for nonfinancial performance accounting, and the prospect of widespread “integrated reporting” seems realistic. Companies are investing in “purpose” and defining their contributions to society against material ESG factors and SDG goals. Corporate sustainability and CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) functions, historically on the sidelines, are now being integrated into line business activity, with progressive companies expanding the scope of competition to include differentiation on environmental and societal dimensions. And through industry consortia, many companies are taking collective action on issues that both threaten their right to operate and open up new opportunities for their industries.

Such examples are important early signals that the context for business is changing. However, for all the progress on commitments, agreements, metrics, and policies, there has been little aggregate progress against top-level goals, like

- reducing CO2 emissions,

- cutting plastics waste,

- or narrowing social and economic inequality within nations.

Without demonstrable impact and collective progress, social and political pressure will only build, further threatening the legitimacy of corporate capitalism.

A New Societal Context for Business

Companies will face escalating social activism by investors, stakeholders, social mission organizations, and policymakers on issues of

- climate risk,

- economic inequality,

- and societal well-being.

Governments and local communities will set a higher bar for a company’s right to operate, and in a connected world a company’s local performance will quickly affect its global reputation and trigger social and regulatory consequences. Stakeholders will expect radical transparency on ESG performance.

This will shift investors’ perceptions of a company’s risk and opportunity, skewing capital toward those that deliver both financial returns and positive societal impact. To satisfy a growing demographic of socially minded consumers and businesses, companies will need to demonstrate “good products doing good” and anchor their brands and identity around a credible purpose.

Talent will gravitate toward companies that give employees a line-of-sight to making the world better while also providing a fulfilling career. To win, companies will need to define competition more broadly, adding new dimensions of value through

- environmental sustainability,

- holistic well-being,

- economic inclusion,

- and ethical content.

This will require radical business model innovation

- to enable circular economies for precious resources;

- to provide assets that are shared rather than owned;

- to broaden access and inclusion;

- and to multiply positive societal impact.

At this critical moment for corporate capitalism, business is more trusted than government, according to the Edelman Trust Barometer. Farsighted corporate leaders will see the opportunity for their industries to

- mitigate environmental and societal threats,

- catalyze collective action to discover new solutions,

- shape wider ecosystems,

- and expand trust with stakeholders.

Such actions will be indispensable to strengthen social permission for corporate capitalism before it is further undermined.

CEOs Need an Agenda for Value and the Common Good

We frame the journey to new corporate value and the common good around six imperatives.

It begins with reimagining corporate strategy, then

- involves transforming the business model,

- reframing performance and scorekeeping,

- leading a purpose-filled organization,

- practicing corporate statesmanship,

- and elevating governance.

While challenging to execute, we argue that this agenda will be essential to create a great company, a great stock, a great impact, and a great legacy.

Reimagine Corporate Strategy

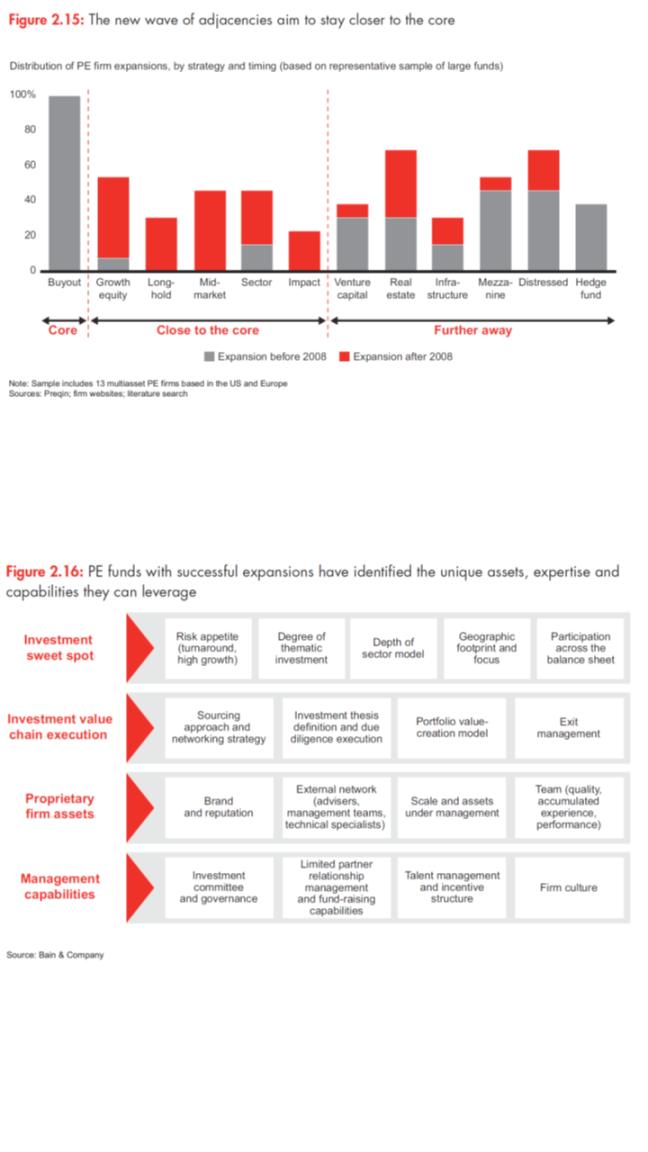

We believe few companies have strategies for this new era of business. The following exhibit illustrates the ambition of such a strategy, which establishes competitive advantage at the intersection of

- shareholder value,

- corporate longevity,

- and societal impact.

The “quality” of the strategy is thus judged by how it delivers both total shareholder returns and total societal impact.

Consequently, it widens the scope of competition to encompass creating rich differentiation and relative advantage in multiple areas of societal value. It embeds “social value” into new business constructs, shared value chains, and reconstructed ecosystems.

It also opens, broadens, and deepens markets to enable access and inclusion. And it expands the scope of business by calling for coalitions for collective action that address existential risks to environmental and societal ecosystems.

This new type of strategy flips leadership’s perspective from “company-out” to “societal needs-in,” by asking how a specific SDG target could be met by extending the company’s capabilities, assets, products, services, and ecosystem—and those of its industry. The following exhibit lists ten questions that strategists should incorporate into their strategy processes to ensure that they embrace the opportunity to create both shareholder returns and societal impact.

However, these new strategies cannot simply be grafted onto existing business models. Business models themselves will need to be transformed. Sustainable business model innovation (S-BMI) takes a much wider perspective than traditional business model innovation by considering

- a broader set of stakeholders;

- the system dynamics of the socio-environmental context;

- longer time horizons for sustaining adaptable advantage;

- the limits of business model scale, viability, and resilience;

- the cradle-to-grave production and consumption cycle;

- and the points of leverage for profitable and sustainable transformation.

Transform Business Models

We can already observe seven topologies for sustainable business model innovation, sometimes in combination, all with the potential to increase both financial returns and societal benefits.

- Own the origins. Compete on capturing and differentiating the “social value” of inputs to production processes, products, or services. For example,

- pursue cleaner energy,

- sustainable practices,

- preserved biodiversity,

- recycled content,

- inclusive and empowering work practices,

- minimized waste,

- digitized traceability,

- fair trade, and so on.

Performance here will require differentially advancing the societal performance of the supplier base and its stewardship of resources, communities, and trade flows. Achieving this may require backward integration to ensure fast and complete upstream transformation and then holding and using these new capabilities for competitive advantage and differentiation.

- Own the whole cycle. Compete by creating societal impact through the whole product usage cycle, from creation through end of life. This competitive typology puts a wide aperture on the business and requires systems analysis to uncover business models that offer the richest competitive and financial options. For example,

- designing for circularity, recyclability, and waste to value;

- creating offerings that enable sharing rather than owning to ensure high utilization of resources and end-of-life value;

- constructing infrastructure to facilitate circularity and repurposing;

- integrating into other value chains to capture societal value;

- educating and enabling consumers to choose whole-cycle propositions on the basis of value to people and planet.

To achieve these ends, expect to reposition operations, reinvent supply chains and distribution networks, pursue new backward or forward integration, acquire business adjacencies, or undertake unconventional strategic partnering.

- Expand “social value.” Compete by expanding the value of products or services on six dimensions:

- economic gains,

- environmental sustainability,

- customer well-being,

- ethical content,

- societal enablement,

- and access and inclusion.

Then advocate new standards, increase transparency and traceability, tune marketing and segmentation, engage customers on the product’s wider value and their involvement in bigger change, and seek premium pricing. In business-to-business offerings, help customers integrate the full social value of your products, services, and business model into their own differentiation and ESG ambitions.

- Expand the chains. Compete by extending the company’s value chain, layering onto other industries’ value chains to extend the reach of your products and services and the societal impact for both parties, while changing the economics and risks of doing so. For example,

- use the reach of a consumer products distribution system to extend payments and financial services to small merchants;

- layer one company’s health services onto another company’s physical supply chain to benefit its workers and their families while expanding markets for health services;

- or use the byproducts of one company’s operations as feedstock in other companies’ value chains.

- Energize the brand. Compete by digitally encoding, promoting, and monetizing the full accumulated social value that is embedded in products and services, along the whole value chain— from origins to customer, from cradle to grave. Use such data to rethink differentiation, the brand experience, customer engagement, pricing for value, ESG reporting, investor engagement, and even potential new businesses. For example,

- strengthen the brand with promotions that showcase the business’s performance on the open, clean, green, renewable, and inclusive attributes of its operations;

- and increase customer engagement and loyalty by using data on the product’s environmental and societal footprint to empower customers in choosing how their lifestyle affects the planet and its people.

- Relocalize and regionalize. Compete by contracting and reconnecting global value chains to bring societal benefits closer to home markets in ways stakeholders value. For example,

- build local and regional brands that better express local tastes and values;

- source from smaller local producers to minimize logistics emissions and strengthen local economies;

- reimagine production networks against total environmental and societal costs;

- capture local waste streams as feedstocks for other activities;

- or reconstitute jobs for microwork to use local talent.

- Build across sectors. Compete by creating models that include the public and social sectors to improve the company’s business and societal proposition, particularly in emerging and rapidly developing economies. For example,

- work alongside governmental bilateral aid institutions and NGO development organizations to improve the agricultural capacity of small farmers so they become reliable sources of agricultural inputs to the agro-processing value chain;

- partner with global environmental organizations and governments to promote the reuse of ocean plastics as feedstocks to production systems;

- partner with governments to strengthen social safety nets and prevent corruption through digitization and electronic payments;

- or partner across sectors to restructure recycling systems to enable higher penetration of waste-to-value business models.

Extend this into industry coalitions for collective action that reshape broader rights to operate and generate new opportunities.

All seven types of S-BMI create new sources of differentiation, operating advantage, network dynamics, and societal value — enabling more durable and resilient businesses that benefit shareholders and society. But to assess and improve the performance of these business models and communicate their value, we need to expand today’s scorecards.

Click her to access BCG’s full article