Turning a Regulatory Requirement Into Competitive Advantage

Mandated enterprise stress testing – the primary macro-prudential tool that emerged from the 2008 financial crisis – helps regulators address concerns about the state of the banking industry and its impact on the local and global financial system. These regulatory stress tests typically focus on the largest banking institutions and involve a limited set of prescribed downturn scenarios.

Regulatory stress testing requires a significant investment by financial institutions – in technology, skilled people and time. And the stress testing process continues to become even more complex as programs mature and regulatory expectations keep growing.

The question is, what’s the best way to go about stress testing, and what other benefits can banks realize from this investment? Equally important, should you view stress testing primarily as a regulatory compliance tool? Or can banks harness it as a management tool that links corporate planning and risk appetite – and democratizes scenariobased analysis across the institution for faster, better business decisions?

These are important questions for every bank executive and risk officer to answer because justifying large financial investments in people and technology solely to comply with periodic regulatory requirements can be difficult. Not that noncompliance is ever an option; failure can result in severe damage to reputation and investor confidence.

But savvy financial institutions are looking for – and realizing – a significant return on investment by reaching beyond simple compliance. They are seeing more effective, consistent analytical processes and the ability to address complex questions from senior management (e.g., the sensitivity of financial performance to changes in macroeconomic factors). Their successes provide a road map for those who are starting to build – or are rethinking their approach to – their stress testing infrastructure.

This article reviews the maturation of regulatory stress test regimes and explores diverse use cases where stress testing (or, more broadly, scenario-based analysis) may provide value beyond regulatory stress testing.

Comprehensive Capital Assessments: A Daunting Exercise

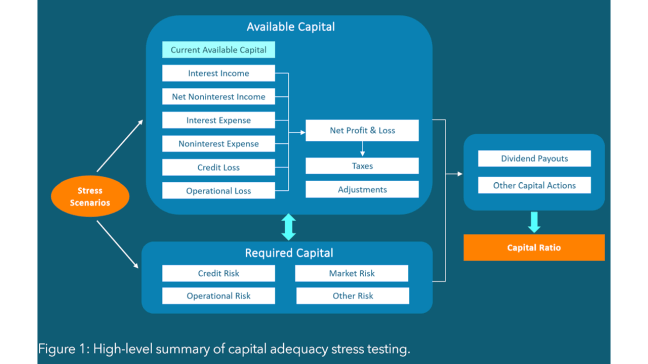

The regulatory stress test framework that emerged following the 2008 financial crisis – that banks perform capital adequacy-oriented stress testing over a multiperiod forecast horizon – is summarized in Figure 1. At each period, a scenario exerts its impact on the net profit or loss based on the

- as-of-date business,

- including portfolio balances,

- exposures,

- and operational income and costs.

The net profit or loss, after being adjusted by other financial obligations and management actions, will determine the capital that is available for the next period on the scenario path.

Note that the natural evolution of the portfolio and business under a given scenario leads to a state of the business at the next horizon, which then starts a new evaluation of the available capital. The risk profile of this business evaluation also determines the capital requirement under the same scenario. The capital adequacy assessment can be performed through this dynamic analysis of capital supply and demand.

This comprehensive capital assessment requires cooperation from various groups across business and finance in an institution. But it becomes a daunting exercise on a multiperiod scenario because of the forward-looking and path-dependent nature of the analysis. For this reason, some jurisdictions began the exercise with only one horizon. Over time, these requirements have been revised to cover at least two horizons, which allows banks to build more realistic business dynamics into their analysis.

Maturing and Optimizing Regulatory Stress Testing

Stress testing – now a standard supervisory tool – has greatly improved banking sector resilience. In regions where stress testing capabilities are more mature, banks have built up adequate capital and have performed well in recent years. For example, the board of governors for both the US Federal Reserve System and Bank of England announced good results for their recent stress tests on large banks.

As these programs mature, many jurisdictions are raising their requirements, both quantitively and qualitatively. For example:

- US CCAR and Bank of England stress tests now require banks to carry out tests on institution-specific scenarios, in addition to prescribed regulatory scenarios.

- The regions adopting IFRS 9, including the EU, Canada and the UK, are now required to incorporate IFRS 9 estimates into regulatory stress tests. Likewise, banks subject to stress testing in the US will need to incorporate CECL estimates into their capital adequacy tests.

- Liquidity risk has been incorporated into stress tests – especially as part of resolution and recovery planning – in regions like the US and UK.

- Jurisdictions in Asia (such as Taiwan) have extended the forecast horizons for their regulatory stress tests.

In addition, stress testing and scenario analysis are now part of Pillar 2 in the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) published by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Institutions are expected to use stress tests and scenario analyses to improve their understanding of the vulnerabilities that they face under a wide range of adverse conditions. Further uses of regulatory stress testing include the scenariobased analysis for Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (IRRBB).

Finally, the goal of regulatory stress testing is increasingly extending beyond completing a simple assessment. Management must prepare a viable mitigation plan should an adverse condition occur. Some regions also require companies to develop “living wills” to ensure the orderly wind-down of institutions and to prevent systemic contagion from an institutional failure.

All of these demands will require the adoption of new technologies and best practices.

Exploring Enhanced Use Cases for Stress Testing Capabilities

As noted by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in its 2018 publication Stress Testing Principles, “Stress testing is now a critical element of risk management for banks and a core tool for banking supervisors and macroprudential authorities.” As stress testing capabilities have matured, people are exploring how to use these capabilities for strategic business purposes – for example, to perform “internal stress testing.”

The term “internal stress testing” can seem ambiguous. Some stakeholders don’t understand the various use cases for applying scenario-based analyses beyond regulatory stress testing or doubt the strategic value to internal management and planning. Others think that developing a scenario-based analytics infrastructure that is useful across the enterprise is just too difficult or costly.

But there are, in fact, many high-impact strategic use cases for stress testing across the enterprise, including:

- Financial planning.

- Risk appetite management.

- What-if and sensitivity analysis.

- Emerging risk identification.

- Reverse stress testing.

Financial Planning

Stress testing is one form of scenario-based analysis. But scenario-based analysis is also useful for forward-looking financial planning exercises on several fronts:

- The development of business plans and management actions are already required as part of regulatory stress testing, so it’s natural to align these processes with internal planning and strategic management.

- Scenario-based analyses lay the foundation for assessing and communicating the impacts of changing environmental factors and portfolio shifts on the institution’s financial performance.

- At a more advanced level, banks can incorporate scenario-based planning with optimization techniques to find an optimal portfolio strategy that performs robustly across a range of scenarios.

Here, banks can leverage the technologies and processes used for regulatory stress testing. However, both the infrastructure and program processes must be developed with flexibility in mind – so that both business-as-usual scenarios and alternatives can be easily managed, and the models and assumptions can be adjusted.

Risk Appetite Management

A closely related topic to stress testing and capital planning is risk appetite. Risk appetite defines the level of risk an institution is willing to take to achieve its financial objectives. According to Senior Supervisors Group (2008), a clearly articulated risk appetite helps financial institutions properly understand, monitor, and communicate risks internally and externally.

Figure 2 illustrates the dynamic relationship between stress testing, risk appetite and capital planning. Note that:

- Risk appetite is defined by the institution to reflect its capital strategy, return targets and its tolerance for risk.

- Capital planning is conducted in alignment with the stated risk appetite and risk policy.

- Scenario-based analyses are then carried out to ensure the bank can operate within the risk appetite under a range of scenarios (i.e., planning, baseline and stressed).

Any breach of the stated risk appetite observed in these analyses leads to management action. These actions may include, but are not limited to,

- enforcement or reallocation of risk limits,

- revisions to capital planning

- or adjustments to current risk appetite levels.

What-If and Sensitivity Analysis

Faster, richer what-if analysis is perhaps the most powerful – and demanding – way to extend a bank’s stress testing utility. What-if analyses are often initiated from ad hoc requests made by management seeking timely insight to guide decisions. Narratives for these scenarios may be driven by recent news topics or unfolding economic events.

An anecdotal example illustrates the business value of this type of analysis. Two years ago, a chief risk officer at one of the largest banks in the United States was at a dinner event and heard concerns about Chinese real estate and a potential market crash. He quickly asked his stress testing team to assess the impact on the bank if such an event occurred. His team was able to report back within a week. Fortunately, the result was not bad – news that was a relief to the CRO.

The responsiveness exhibited by this CRO’s stress testing team is impressive. But speed alone is not enough. To really get value from what-if analysis, banks must also conduct it with a reasonable level of detail and sophistication. For this reason, banks must design their stress test infrastructure to balance comprehensiveness and performance. Otherwise, its value will be limited.

Sensitivity analysis usually supplements stress testing. It differs from other scenariobased analyses in that the scenarios typically lack a narrative around them. Instead, they are usually defined parametrically to answer questions about scenario, assumption and model deviations.

Sensitivity analysis can answer questions such as:

- Which economic factors are the most significant for future portfolio performance?

- What level of uncertainty results from incremental changes to inputs and assumptions?

- What portfolio concentrations are most sensitive to model inputs?

For modeling purposes, sensitivity tests can be viewed as an expanded set of scenario analyses. Thus, if banks perform sensitivity tests, they must be able to scale their infrastructure to complete a large number of tests within a reasonable time frame and must be able to easily compare the results.

Emerging Risk Identification

Econometric-based stress testing of portfolio-level credit, market, interest rate and liquidity risks is now a relatively established practice. But measuring the impacts from other risks, such as reputation and strategic risk, is not trivial. Scenario-based analysis provides a viable solution, though it requires proper translation from the scenarios involving these risks into a scenario that can be modeled. This process often opens a rich dialogue across the institution, leading to a beneficial consideration of potential business impacts.

Reverse Stress Testing

To enhance the relevance of the scenarios applied in stress testing analyses, many regulators have required banks to conduct reverse stress tests. For reverse stress tests, institutions must determine the risk factors that have a high impact on their business and determine scenarios that result in the breaching thresholds of specific output metrics (e.g., total capital ratio).

There are multiple approaches to reverse stress testing. Skoglund and Chen proposed a method leveraging risk information measures to decompose the risk factor impact from simulations and apply the results for stress testing. Chen and Skoglund also explained how stress testing and simulation can leverage each other for risk analyses.

Assessing the Impacts of COVID-19

The worldwide spread of COVID-19 in 2020 has presented a sudden shock to the financial plans of lending institutions. Both the spread of the virus and the global response to it are highly dynamic. Bank leaders, seeking a timely understanding of the potential financial impacts, have increasingly turned to scenario analysis. But, to be meaningful, the process must:

- Scale to an increasing array of input scenarios as the situation continues to develop.

- Provide a controlled process to perform and summarize numerous iterations of analysis.

- Provide understandable and explainable results in a timely fashion.

- Provide process transparency and control for qualitative and quantitative assumptions.

- Maintain detailed data to support ad hoc reporting and concentration analysis.

Banks able to conduct rapid ad hoc analysis can respond more confidently and provide a data-driven basis for the actions they take as the crisis unfolds.

Conclusion

Regulatory stress testing has become a primary tool for bank supervision, and financial institutions have dedicated significant time and resources to comply with their regional mandates. However, the benefits of scenario-based analysis reach beyond such rote compliance.

Leading banks are finding they can expand the utility of their stress test programs to

- enhance their understanding of portfolio dynamics,

- improve their planning processes

- and better prepare for future crises.

Through increased automation, institutions can

- explore a greater range of scenarios,

- reduce processing time and effort,

- and support the increased flexibility required for strategic scenario-based analysis.

Armed with these capabilities, institutions can improve their financial performance and successfully weather downturns by making better, data-driven decisions.

Click here to access SAS’ latest Whitepaper