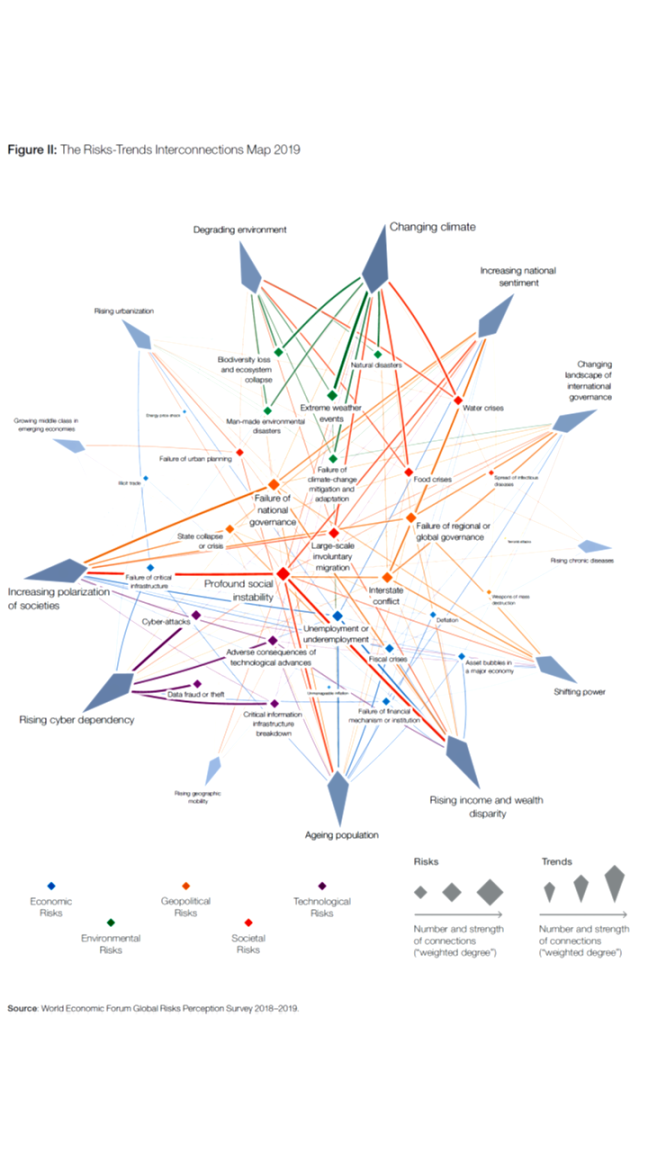

Is the world sleepwalking into a crisis? Global risks are intensifying but the collective will to tackle them appears to be lacking. Instead, divisions are hardening. The world’s move into a new phase of strongly state-centred politics, noted in last year’s Global Risks Report, continued throughout 2018. The idea of “taking back control”— whether domestically from political rivals or externally from multilateral or supranational organizations — resonates across many countries and many issues. The energy now expended on consolidating or recovering national control risks weakening collective responses to emerging global challenges. We are drifting deeper into global problems from which we will struggle to extricate ourselves.

During 2018, macroeconomic risks moved into sharper focus. Financial market volatility increased and the headwinds facing the global economy intensified. The rate of global growth appears to have peaked: the latest International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts point to a gradual slowdown over the next few years. This is mainly the result of developments in advanced economies, but projections of a slowdown in China—from 6.6% growth in 2018 to 6.2% this year and 5.8% by 2022—are a source of concern. So too is the global debt burden, which is significantly higher than before the global financial crisis, at around 225% of GDP. In addition, a tightening of global financial conditions has placed particular strain on countries that built up dollar-denominated liabilities while interest rates were low.

Geopolitical and geo-economic tensions are rising among the world’s major powers. These tensions represent the most urgent global risks at present. The world is evolving into a period of divergence following a period of globalization that profoundly altered the global political economy. Reconfiguring the relations of deeply integrated countries is fraught with potential risks, and trade and investment relations among many of the world’s powers were difficult during 2018.

Against this backdrop, it is likely to become more difficult to make collective progress on other global challenges—from protecting the environment to responding to the ethical challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Deepening fissures in the international system suggest that systemic risks may be building. If another global crisis were to hit, would the necessary levels of cooperation and support be forthcoming? Probably, but the tension between the globalization of the world economy and the growing nationalism of world politics is a deepening risk.

Environmental risks continue to dominate the results of our annual Global Risks Perception Survey (GRPS). This year, they accounted for three of the top five risks by likelihood and four by impact. Extreme weather was the risk of greatest concern, but our survey respondents are increasingly worried about environmental policy failure: having fallen in the rankings after Paris, “failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation” jumped back to number two in terms of impact this year. The results of climate inaction are becoming increasingly clear. The accelerating pace of biodiversity loss is a particular concern. Species abundance is down by 60% since 1970. In the human food chain, biodiversity loss is affecting health and socioeconomic development, with implications for well-being, productivity, and even regional security.

Technology continues to play a profound role in shaping the global risks landscape. Concerns about data fraud and cyber-attacks were prominent again in the GRPS, which also highlighted a number of other technological vulnerabilities: around two-thirds of respondents expect the risks associated with fake news and identity theft to increase in 2019, while three-fifths said the same about loss of privacy to companies and governments. There were further massive data breaches in 2018, new hardware weaknesses were revealed, and research pointed to the potential uses of artificial intelligence to engineer more potent cyberattacks. Last year also provided further evidence that cyber-attacks pose risks to critical infrastructure, prompting countries to strengthen their screening of cross-border partnerships on national grounds.

The importance of the various structural changes that are under way should not distract us from the human side of global risks. For many people, this is an increasingly anxious, unhappy and lonely world. Worldwide, mental health problems now affect an estimated 700 million people. Complex transformations— societal, technological and work-related—are having a profound impact on people’s lived experiences. A common theme is psychological stress related to a feeling of lack of control in the face of uncertainty. These issues deserve more attention: declining psychological and emotional wellbeing is a risk in itself—and one that also affects the wider global risks landscape, notably via impacts on social cohesion and politics.

Another set of risks being amplified by global transformations relate to biological pathogens. Changes in how we live have increased the risk of a devastating outbreak occurring naturally, and emerging technologies are making it increasingly easy for new biological threats to be manufactured and released either deliberately or by accident. The world is badly under-prepared for even modest biological threats, leaving us vulnerable to potentially huge impacts on individual lives, societal well-being, economic activity and national security. Revolutionary new biotechnologies promise miraculous advances, but also create daunting challenges of oversight and control—as demonstrated by claims in 2018 that the world’s first genemodified babies had been created.

Rapidly growing cities and ongoing effects of climate change are making more people vulnerable to rising sea levels. Two-thirds of the global population is expected to live in cities by 2050 and already an estimated 800 million people live in more than 570 coastal cities vulnerable to a sea-level rise of 0.5 metres by 2050. In a vicious circle, urbanization not only concentrates people and property in areas of potential damage and disruption, it also exacerbates those risks— for example by destroying natural sources of resilience such as coastal mangroves and increasing the strain on groundwater reserves. Intensifying impacts will render an increasing amount of land uninhabitable. There are three main strategies for adapting to rising sea-levels:

- engineering projects to keep water out,

- naturebased defences,

- and peoplebased strategies, such as moving households and businesses to safer ground or investing in social capital

to make flood-risk communities more resilient.

In this year’s Future Shocks section, we focus again on the potential for threshold effects that could trigger dramatic deteriorations and cause cascading risks to crystallize with dizzying speed. Each of the 10 shocks we present is a “what-if” scenario—not a prediction, but a reminder of the need to think creatively about risk and to expect the unexpected. Among the topics covered this year are

- quantum cryptography,

- monetary populism,

- affective computing

- and the death of human rights.

In the Risk Reassessment section, experts share their insights about how to manage risks. John Graham writes about weighing the trade-offs between different risks, and András Tilcsik and Chris Clearfield write about how managers can minimize the risk of systemic failures in their organizations.

And in the Hindsight section, we revisit three of the topics covered in previous reports:

- food security,

- civil society

- and infrastructure investment.

click here to access wef-mmc-zurich’s global risks report 2019