Risk management is the foundation upon which financial institutions are built. Recognizing risk in all its forms—measuring it, managing it, mitigating it—are all critical to success. But has every firm achieved that goal? It doesn’t take indepth research beyond the myriad of breach headlines to answer that question.

But many important questions remain: What are key dimensions of the financial sector Internet risk surface? How does that surface compare to other sectors? Which specific industries within Financial Services appear to be managing that risk better than others? We take up these questions and more in this report.

- The financial sector boasts the lowest rate of high and critical security exposures among all sectors. This indicates they’re doing a good job managing risk overall.

- But not all types of financial service firms appear to be managing risk equally well. For example, the rate of severe findings in the smallest commercial banks is 4x higher than that of the largest banks.

- It’s not just small community banks struggling, however. Securities and Commodities firms show a disconcerting combination of having the largest deployment of high-value assets AND the highest rate of critical security exposures.

- Others appear to be exceeding the norm. Take credit card issuers: they typically have the largest Internet footprint but balance that by maintaining the lowest rate of security exposures.

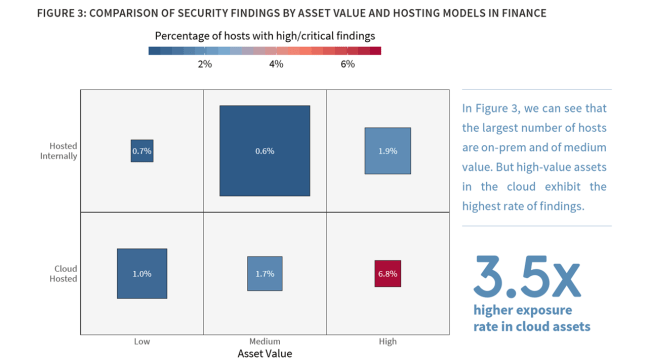

- Many other challenges and risk factors exist. For instance, the industry average rate of severe security findings in critical cloud-based assets is 3.5x that of assets hosted on-premises.

Dimensions of the Financial Sector Risk Surface

As Digital Transformation ushers in a plethora of changes, critical areas of risk exposure are also changing and expanding. We view the risk surface as anywhere an organization’s ability to operate, reputation, assets, legal obligations, or regulatory compliance is at risk. The aspects of a firm’s risk exposure that are associated with or observable from the internet are considered its internet risk surface. In Figure 1, we compare five key dimensions of the internet risk surface across different industries and highlight where the financial sector ranks among them.

- Hosts: Number of internet-facing assets associated with an organization.

- Providers: Number of external service providers used across hosts.

- Geography: Measure of the geographic distribution of a firm’s hosts.

- Asset Value: Rating of the data sensitivity and business criticality of hosts based on multiple observed indicators. High value systems that include those that collect GDPR and CCPA regulated information.

- Findings: Security-relevant issues that expose hosts to various threats, following the CVSS rating scale.

The values recorded in Figure 1 for these dimensions represent what’s “typical” (as measured by the mean or median) among organizations within each sector. There’s a huge amount of variation, meaning not all financial institutions operate more external hosts than all realtors, but what you see here is the general pattern. The blue highlights trace the ranking of Finance along each dimension.

Financial firms are undoubtedly aware of these tendencies and the need to protect those valuable assets. What’s more, that awareness appears to translate fairly effectively into action. Finance boasts the lowest rate of high and critical security exposures among all sectors. We also ran the numbers specific to high-value assets, and financial institutions show the lowest exposure rates there too. All of this aligns pretty well with expectations—financial firms keep a tight rein on their valuable Internet-exposed assets.

This control tendency becomes even more apparent when examining the distribution of hosts with severe findings in Figure 2. Blue dots mark the average exposure rate for the entire sector (and correspond to values in Figure 1), while the grey bars indicate the amount of variation among individual organizations within each sector. The fact that Finance exhibits the least variation shows that even rotten apples don’t fall as far from the Finance tree as they often do in other sectors. Perhaps a rising tide lifts all boats?

Security Exposures in Financial Cloud Deployments

We now know financial institutions do well minimizing security findings, but does that record stand equally strong across all infrastructure? Figure 3 answers that question by featuring four of the five key risk surface dimensions:

- the proportion of hosts (square size),

- asset value (columns),

- hosting location (rows),

- and the rate of severe security findings (color scale and value label).

This view facilitates a range of comparisons, including the relative proportion of assets hosted internally vs. in the cloud, how asset value distributes across hosting locales, and where high-severity issues accumulate.

From Figure 3, box sizes indicate that organizations in the financial sector host a majority of their Internet-facing systems on-premises, but do leverage the cloud to a greater degree for low-value assets. The bright red box makes it apparent that security exposures concentrate more acutely in high-value assets hosted in the cloud. Overall, the rate of severe findings in cloud-based assets is 3.5x that of on-prem. This suggests the angst many financial firms have over moving to the cloud does indeed have some merit. But when we examine the Finance sector relative to others in Figure 4 the intensity of exposures in critical cloud assets appears much less drastic.

In Figure 3, we can see that the largest number of hosts are on-prem and of medium value. But high-value assets in the cloud exhibit the highest rate of findings.

Given that cloud vs. on-prem exposure disparity, we feel the need to caution against jumping to conclusions. We could interpret these results to proclaim that the cloud isn’t ready for financial applications and should be avoided. Another interpretation could suggest that it’s more about organizational readiness for the cloud than the inherent insecurity of the cloud. Either way, it appears that many financial institutions migrating to the cloud are handling that paradigm shift better than others.

It must also be noted that not all cloud environments are the same. Our Cloud Risk Surface report discovered an average 12X difference between cloud providers with the highest and lowest exposure rates. We still believe this says more about the typical users and use cases of the various cloud platforms than any intrinsic security inequalities. But at the same time, we recommend evaluating cloud providers based on internal features as well as tools and guidance they make available to assist customers in securing their environments. Certain clouds are undoubtedly a better match for financial services use cases while others less so.

Risk Surface of Subsectors within Financial Services

Having compared Finance to other sectors at a high level, we now examine the risk surface of major subsectors of financial services according to the following NAICS designations:

- Insurance Carriers: Institutions engaged in underwriting and selling annuities, insurance policies, and benefits.

- Credit Intermediation: Includes banks, savings institutions, credit card issuers, loan brokers, and processors, etc.

- Securities & Commodities: Investment banks, brokerages, securities exchanges, portfolio management, etc.

- Central Banks: Monetary authorities that issue currency, manage national money supply and reserves, etc.

- Funds & Trusts: Funds and programs that pool securities or other assets on behalf of shareholders or beneficiaries.

Figure 5 compares these Finance subsectors along the same dimensions used in Figure 1. At the top, we see that Insurance Carriers generally maintain a large Internet surface area (hosts, providers, countries), but a comparatively lower ranking for asset value and security findings. The Credit Intermediation subsector (the NAICS designation that includes banks, brokers, creditors, and processors) follows a similar pattern. This indicates that such organizations are, by and large, able to maintain some level of control over their expanding risk surface.

A leading percentage of high-value assets and a leading percentage of highly critical security findings for the Securities and Commodities subsector is a disconcerting combination. It suggests either unusually high risk tolerance or ineffective risk management (or both), leaving those valuable assets overexposed. The Funds and Trusts subsector exhibits a more riskaverse approach to minimizing exposures across its relatively small digital footprint of valuable assets.

Risk Surface across Banking Institutions

Given that the financial sector is so broad, we thought a closer examination of the risk surface particular to banking institutions was in order. Banks have long concerned themselves with risk. Well before the rise of the Internet or mobile technologies, banks made their profits by determining how to gauge the risk of potential borrowers or loans, plotting the risk and reward of offering various deposit and investment products, or entering different markets, allowing access through several delivery channels. It could be said that the successful management and measurement of risk throughout an organization is perhaps the key factor that has always determined the relative success or failure of any bank.

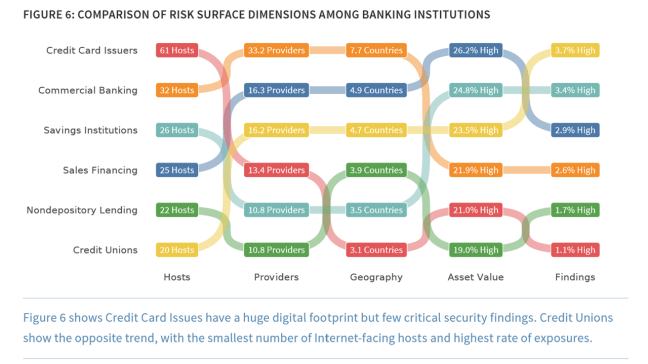

As a highly-regulated industry in most countries, banking institutions must also consider risk from more than a business or operational perspective. They must take into account the compliance requirements to limit risk in various areas, and ensure that they are properly securing their systems and services in a way that meets regulatory standards. Such pressures undoubtedly affect the risk surface and Figure 6 hints at those effects on different types of banking institutions.

Credit card issuers earn the honored distinction of having the largest average number of Internet-facing hosts (by far) while achieving the lowest prevalence of severe security findings. Credit unions flip this trend with the fewest hosts and most prevalent findings. This likely reflects the perennial struggle of credit unions to get the most bang from their buck.

Traditionally well-resourced commercial banks leverage the most third party providers and have a presence in more countries, all with a better-than-average exposure rate. Our previous research revealed that commercial banks were among the top two generators and receivers of multi-party cyber incidents, possibly due to the size and spread of their risk surface.

Two Things to Consider

- In this interconnected world, third-party and fourth-party risk is your risk. If you are a financial institution, particularly a commercial bank, take a moment to congratulate yourself on managing risk well – but only for a moment. Why? Because every enterprise is critically dependent on a wide array of vendors and partners that span a broad spectrum of industries. Their risk is your risk. The work of your third-party risk team is critically important in holding your vendors accountable to managing your risk interests well.

- Managing risk—whether internal or third-party—requires focus. There are simply too many things to do, giving rise to the endless “hamster wheel of risk management.” A better approach starts with obtaining an accurate picture of your risk surface and the critical exposures across it. This includes third-party relationships, and now fourth-party risk, which bank regulators are now requiring. Do you have the resources to sufficiently manage this? Do you know your risk surface?