Early december 2024 EIOPA has published its consultation paper on management of sustainability risks and the newly created sustainibility risk plans. Very detailed and far reaching standards for the (re)insurance industry that will be added to the ESRS and CSRD framework and significantly enhance existing Solvency II requirements as part of the broader Solvency II reform (Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2009/138/EC as regards proportionality, quality of supervision, reporting, long-term guarantee measures, macro-prudential tools, sustainability risks, group and cross-border supervision).

This article covers the new requirements for governance (AMSB, Key Functions) and the framework for the sustainability risk plans. An upcoming article will deal with materiality and financial assessments covered by the RTS draft as well as with the new metrics to be integrated in the extended framework.

Background and rationale

The Solvency II Directive requires undertakings to implement specific plans to address the financial risks from sustainability factors and mandates EIOPA to specify the elements of these plans. Article 44 of the amended Solvency II Directive requires undertakings to develop and monitor the implementation of specific plans, quantifiable targets, and processes to monitor and address the financial risks arising in the short, medium, and long-term from sustainability factors. The Directive mandates EIOPA to specify in regulatory technical standards (RTS) the minimum standards and reference methodologies for the

- identification,

- measurement,

- management,

- and monitoring

of sustainability risks, the elements to be covered in the plans, the supervision and disclosure of relevant elements of the plans.

According to EIOPA, the RTS apply the following approach:

- First, the proposed RTS build on the existing prudential requirements and integrate the sustainability risk plans into undertakings’ existing risk management practices. The Solvency II Delegated Regulation as amended in 2022 as well as amendments to the Solvency II Directive already require the management of sustainability risks. Existing policy statements and guidance issued by EIOPA set out supervisory expectations on aspects of sustainability risks management. The elements of the sustainability risk plans feed off these requirements and into the own risk and solvency assessment (ORSA) of material financial risks. The sustainability risk plans will be part of undertakings’ regular supervisory reporting.

- Second, the RTS ensure a read-across between the undertakings’ sustainability and transition plans. While the sustainability risk plans focus on prudential risks for insurers arising from sustainability factors, the undertakings’ actions to mitigate these risks will need to consider their transition efforts.

- Third, the RTS enable undertakings, including those that are subject to the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), to disclose on sustainability risk in a consistent and efficient manner. The RTS specify the minimum standards and methodologies, including selected risk metrics, for performing and disclosing on prudential sustainability risks, as required by the Solvency II Directive. Insurers subject to CSRD can feed the elements identified for public disclosure as part of the Solvency II Solvency and Financial Condition Report (SFCR), into the disclosure required under CSRD.

Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA)

Insurers shall integrate sustainability risk assessment in their system of governance, risk management

system and ORSA, as illustrated below:

- Risk management function and areas: the risk management function shall identify and assess emerging and sustainability risks. The sustainability risks identified by the risk management function shall form part of the own solvency needs assessment in the ORSA. Undertakings shall integrate sustainability risks in their policies. This includes the underwriting and investment policies, but also, where relevant policies on other areas (e.g. ALM, liquidity, concentration, operational, reinsurance and other risk mitigating techniques, deferred taxes risk management). The underwriting and reserving policy shall include actions by the undertaking to assess and manage the risk of loss resulting from inadequate pricing and provisioning assumptions due to internal or external factors, including sustainability risks. The investment risk management policy shall include actions by the insurance or reinsurance undertaking to ensure that sustainability risks relating to the investment portfolio are properly identified, assessed, and managed.

- Prudent person investment principle: when identifying, measuring, monitoring, managing, controlling, reporting, and assessing risks arising from investments, undertakings shall take into account the potential long-term impact of their investment strategy and decisions on sustainability factors.

- Actuarial function: regarding the underwriting policy, the opinion to be expressed by the actuarial function shall at least include conclusions on the effect of sustainability risks.

- Remuneration policy: The remuneration policy shall include information on how it takes into account the integration of sustainability risks in the risk management system.

Sustainability Risk Plans

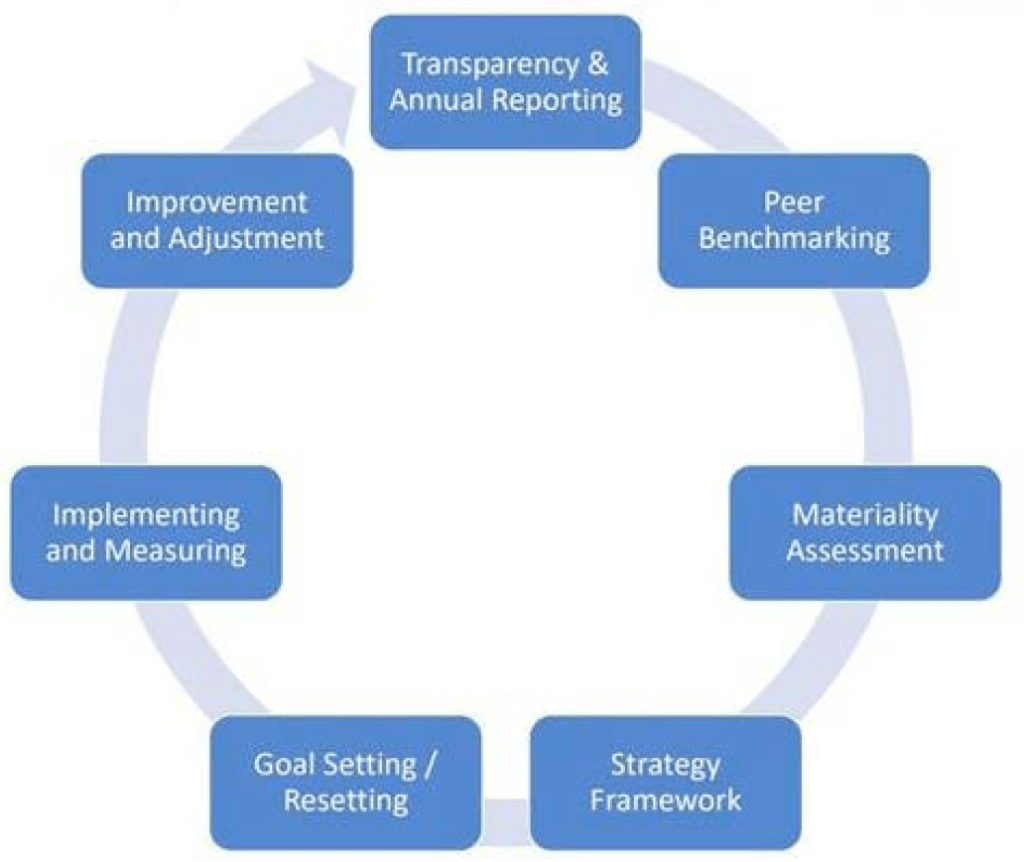

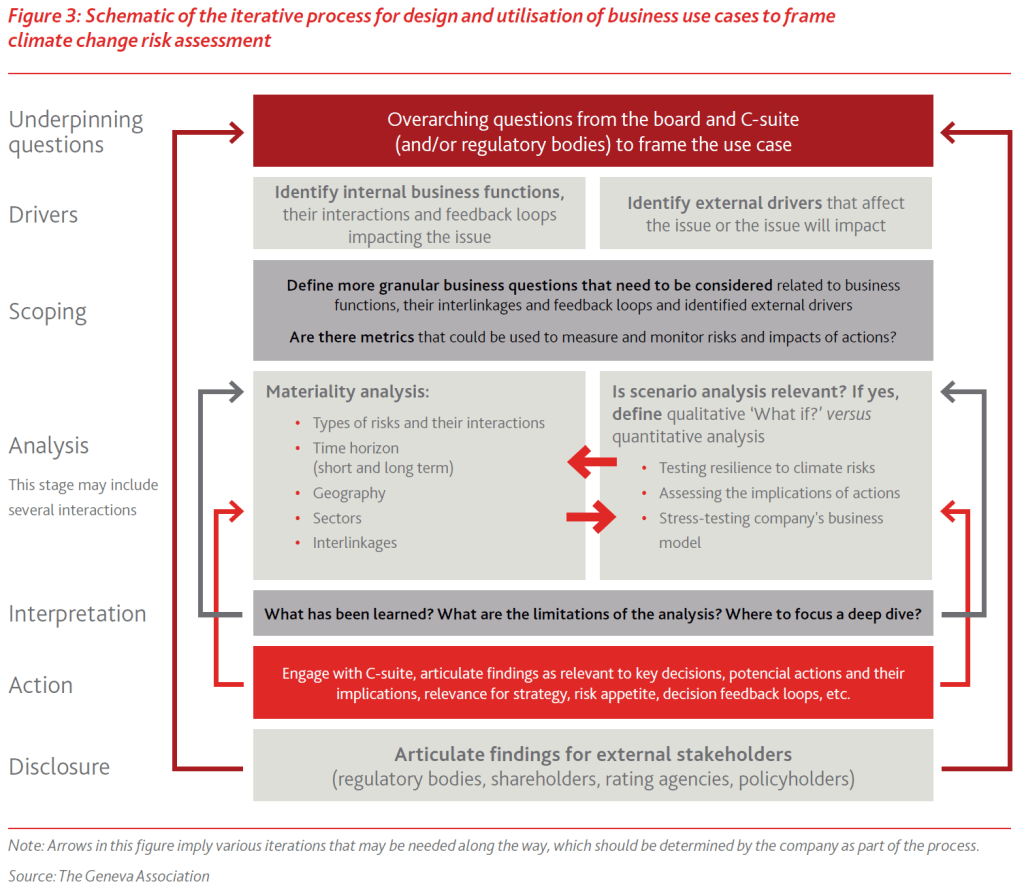

Considering the relationship with the ORSA, regular supervisory reporting and public disclosure, the figure below sets out the structure of the sustainability risk assessment and key elements of the plan:

The sustainability risk plans should be sufficiently robust to support insurers’ risk management process and the supervisory review of the risk management. Considering the information that is required in the ORSA (for material risks), the sustainability risk plans reported to the National Supervisory Authority should include as a minimum:

a) Governance arrangements and policies to identify, assess, manage, and monitor material sustainability risks.

b) A sustainability risk assessment consisting of:

I. A materiality assessment.

II. A financial risk assessment.

c) Explanation of the key results obtained from the materiality assessment and from the financial risk assessment, where applicable

d) The risk metrics, where relevant, based on different scenarios and time horizons.

e) Quantifiable targets over the short, medium, and long term to address material risks in line with the undertaking’s risk appetite and strategy.

f) Actions by which the undertaking manages the sustainability risks according to the targets set.

Governance

Business model and strategy

Sustainability risks and opportunities can affect the business planning over a short-to-medium term and the strategic planning over a longer term.

The Administrative, Management, and Supervisory Body (AMSB) should set risk exposure limits, targets, and thresholds for the risks that the undertaking is willing to bear with regards to sustainability risks, taking into account:

- Short-, medium- and long-term time horizon, considering the impact sustainability risks may have soon, but also over the longer term, to be reflected in the business planning over a short-to-medium term and the strategic planning over a longer term.

- The impact of sustainability risks on the external business environment that will feed into the (re)insurers’ strategic planning.

- The undertaking’s exposure to material sustainability risk, across sectors and geographies, the transmission channels across risk categories and lines of business.

- Qualitative and quantitative results from scenario, sensitivity, and stress testing.

Potentially relevant questions which the undertaking can consider when integrating sustainability risk assessment into its governance are:

How does the AMSB expect that sustainability risks might affect its business?

- Does the AMSB consider sustainability factors as a risk and/or opportunity? If yes, in what ways might environmental, social or governance factors pose risks to the undertaking’s business in economic or financial terms, or create opportunities? If neither risk nor opportunities seem to exist, why not? Has the undertaking elaborated different strategic options to manage the risks and how they have been developed?

- Has the AMSB implemented or planned any substantive changes to its business strategy in response to current and potential future sustainability impacts? If yes, what are the key risk drivers that it would consider relevant to its strategy? If not, why not?

- Is the AMSB concerned about secondary effects or indirect impacts of sustainability on the undertaking’s overall strategy and business model (e.g. any systemic repercussions on the industry or the economy)?

- What is the undertaking’s time horizon for considering environmental, social or governance risks?

Governance

A. The AMSB

Fitness and propriety. The AMSB is responsible for setting undertakings’ risk appetite and making sure that all risks, and therefore also sustainability risks, if material, are effectively identified, managed, and controlled.

For this, the AMSB should collectively possess the appropriate qualification, experience, and knowledge relevant to assess long-term risks and opportunities related to sustainability risks, which may be obtained or improved through appropriate training.

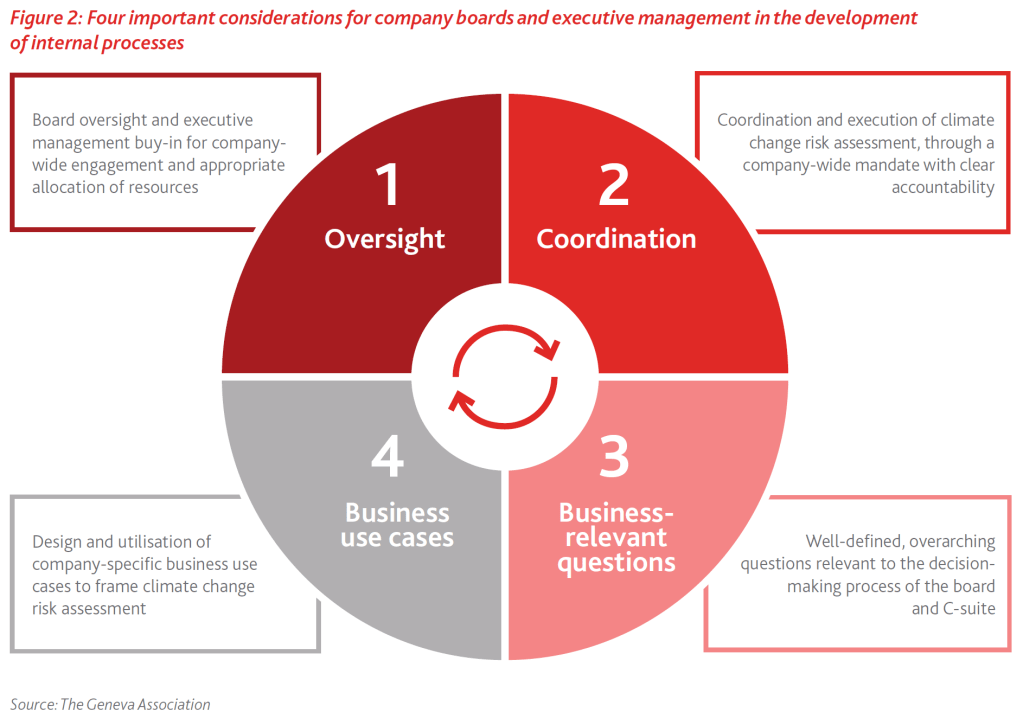

Effectiveness. To ensure the AMSB effectively executes its responsibilities to identify, manage and control sustainability risks, the AMSB should:

- be aware of their obligations in the context of the long-term impacts of sustainability risks.

- be capable of identifying sustainability risks as possible key risks for the undertaking.

- openly discuss within the AMSB sustainability risks and opportunities.

- effectively communicate on sustainability risks as possible key risks to in the short and long term.

- interact with the rest of the organisation by putting sustainability risk as a possible key topic in the day-to-day business.

- plan and deliver results by considering the impact of sustainability risks and opportunities.

- take sustainability risks into consideration in the decision-making process.

B. Risk Management and other Key Functions

The risk management function has a vital role in:

Risk identification and measurement: The risk management function will need to ensure that the undertaking effectively identifies how sustainability risks could materialise within each area of the risk management system. It also sets the approach used by undertakings to measure and quantify their exposure to sustainability risks, including understanding the limitations of the methods used, and any gaps the undertaking faces in data and methodologies to assess the risks. Undertakings need to apply relevant tools to identify risks in a proportionate way depending on the nature, scale, and complexity of the risks.

Given the forward-looking nature of the risks and the inherent uncertainty associated with sustainability risks, undertakings will need to use appropriate methodologies and tools necessary to capture the size and scale of the risks. This would imply going beyond using only historical data for the purposes of the risk assessment and depending on the materiality of risk at stake, implement forward-looking technique (i.e. stress testing and scenario analysis), for example by considering also future trends in catastrophe modelling or environmental risk assessment. Science, data, or tools may not yet be sufficiently developed to estimate the risks accurately. As undertakings’ expertise and practices develops, the expectation should be that the approach to identifying and measuring the sustainability risks will mature over time. Hence, the risk management function will need to establish the following:

- clear policies and procedures for identifying, measure, monitor, managing and report sustainability risks, and the review and approval by the AMSB.

- qualitative, quantitative or a mix of both approaches to appropriately identify and measure the risks, and any limitations to data and tools.

- forward-looking analysis of underwriting liabilities or investment portfolios under different future (transition) scenarios, setting out the key data inputs and assumptions as well as gaps and barriers (information, data, scenarios) which complicate undertaking’s efforts to undertake scenario analysis.

- oversight of any activities performed by the external service providers (e.g. ESG rating providers).

Risk monitoring: The risk management function will need to establish the methodologies, tools, metrics and suitable key risk or performance indicators to monitor the sustainability risks and ensure that risks are consistent with internal limit and its risk appetite. These quantitative and qualitative tools and metrics would aim, for example, at monitoring exposures to climate change-related risk factors which could result from changes in the concentration of the investment or underwriting portfolios, or the potential impact of physical risk factors on outsourcing arrangements and supply chains. The tools and metrics need to be updated regularly to ensure that risks underwritten, or investments made remain in line with undertakings’ risk appetite and support decision making by the AMSB. In addition to that, a list of circumstances which would trigger a review of the strategy for addressing the sustainability risks can be considered as a good practice.

Risk management/mitigation: Risk management measures should be proportionate to the outcome of the materiality assessment. Where material potential impacts of the sustainability risks have been identified, undertaking(s) should identify risk management and mitigating measures. The written policies on the investment and underwriting strategy should include such potential measures. Based on the double materiality principle, the investment and underwriting policy will also consider the financial risks to the balance sheet arising from the impact posed by the underwriting and investment strategy and decisions on sustainability factors. Risk management measures can therefore include measures to help reducing risks caused by climate change, through premium incentives, for example.

The actuarial function shall also consider sustainability risks in its tasks. This would include:

- concluding on the effect of sustainability risks in the opinion on the underwriting policy. For example, considering the increasing expected losses from physical damage due to increasingly severe and frequent natural catastrophes, the choice of underwriting certain perils, but also the pricing of the perils will need to be considered in a forward-looking manner, having regard to the sustainability of the business strategy.

- an opinion on the adequacy of the reinsurance arrangements of the undertaking taking special account of the sustainability risks of the undertaking, the undertaking’s reinsurance policy and the interrelationship between reinsurance and technical provisions. The undertaking may consider that in times of increasing losses due to climate change, the reinsurance market may ‘harden’ and increase the cost for primary reinsurance.

- contributing to the effective implementation of the risk management system, providing the necessary support to the risk management function. For example, considering increasing losses for natural catastrophes due to climate change, the actuarial function will need to contribute to the assessment of the risk and opportunity of underwriting certain natural perils. The actuarial pricing of climate change risks can inform the overall risk management strategy and contribute to the underwriting policy by informing on the risks of underwriting certain perils and the opportunity to invest in prevention measures to reduce the losses. The consideration of climate change in an actuarial risk-based manner should allow for the consideration of incentives in the pricing and underwriting of certain natural hazards, with the view to potentially reduce losses over a longer-term perspective.

- coordinating the calculation of technical provisions and overseeing the calculation of technical provision, including referring to risks to technical provision driven by sustainability factors.

- assessing the sufficiency and quality of the data used in the calculation of technical provisions including the validation of relevant sustainability risk input data and comparison of best estimates against experience. The assessment may include expressing a view on data limitations as well as considerations on how to implement a forward-looking view on the risks.

The role of the compliance function regarding sustainability risks would imply, as part of establishing and implementing the compliance policy:

- assessing legal and legal change risks related to sustainability regulation. Especially as regulatory requirements are building up on sustainability risk management, reporting and disclosure, the compliance with new legal requirements will require attention.

- providing information on the high-risk areas within the undertaking as regards to the transition policy of the company and legal risk attached to implementing (or not) the transition targets, from a prudential and conduct perspective.

- identifying potential measures to prevent or address non-compliance. This may require addressing the risk of misrepresentation at entity or product level on the sustainable nature of its risk management or of its product offer.

The internal audit function should consider, where relevant sustainability risks in the preparation and maintaining of internal audit plan. This may include:

- highlighting high-risk areas to requiring special attention. The potentially increased reliance on external parties as data providers on sustainability risks, or for verification of the sustainability of investments regarding environmental or social objectives, may need particular attention to ascertain the quality of the outsourced activity.

- coping with follow-up actions in particular recommendations in areas, processes, and activities subject to review.

Functions or committees with special responsibility for sustainability risks. The AMSB may decide to delegate the task of addressing sustainability matters to specific committee(s). Such committees discuss and propose matters to the AMSB for it to take appropriate actions and pass resolutions. It is important to highlight that the responsibility about decisions about material sustainability risks remains with the AMSB. If a (re)insurance undertaking has or intends to set up a function with special responsibility for sustainability risks, its integration with existing processes and interface with key and other functions must be clearly defined. A dedicated sustainability unit or function would therefore be involved, in addition to the risk management function, actuarial function and/or compliance function, whenever the insured risk or investment is sensitive to sustainability risk, e.g., by virtue of the economic sector in which the investment was made, or the geographical location of the insured object.

Misunderstandings regarding the role or extent of the assessment to be made by the sustainability function must be avoided. In other words, it needs to be ascertained whether the function has a mere corporate/communication role (e.g. in dealing with corporate responsibility and reputational risks) or is also intended and equipped for sustainability materiality and financial risk analysis.

Remuneration

Remuneration can be used as a tool for the integration of sustainability risks and incentives for

sustainable investment or underwriting decisions. The Solvency II Delegated Regulation stipulates that the remuneration policy and remuneration practices shall be in line with the undertaking’s business and risk management strategy, its risk profile, objectives, risk management practices and the long-term interests and performance of the undertaking. It further stipulates that the remuneration policy shall include information on how it takes into account the integration of sustainability risks in the risk management system.

Furthermore, undertakings within the scope of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation shall include in their remuneration policies information on how those policies are consistent with the integration of sustainability risks, and to publish that information on their websites.

Undertakings will need to take into account both financial and non-financial criteria when assessing

an individual’s performance at certain point of time: the consideration of sustainability factors is an example of non-financial (or increasingly financial) criteria that could be considered when assessing individual performance. For example, increasingly, for investment professionals, the risk framework should include an assessment of sustainability risks.

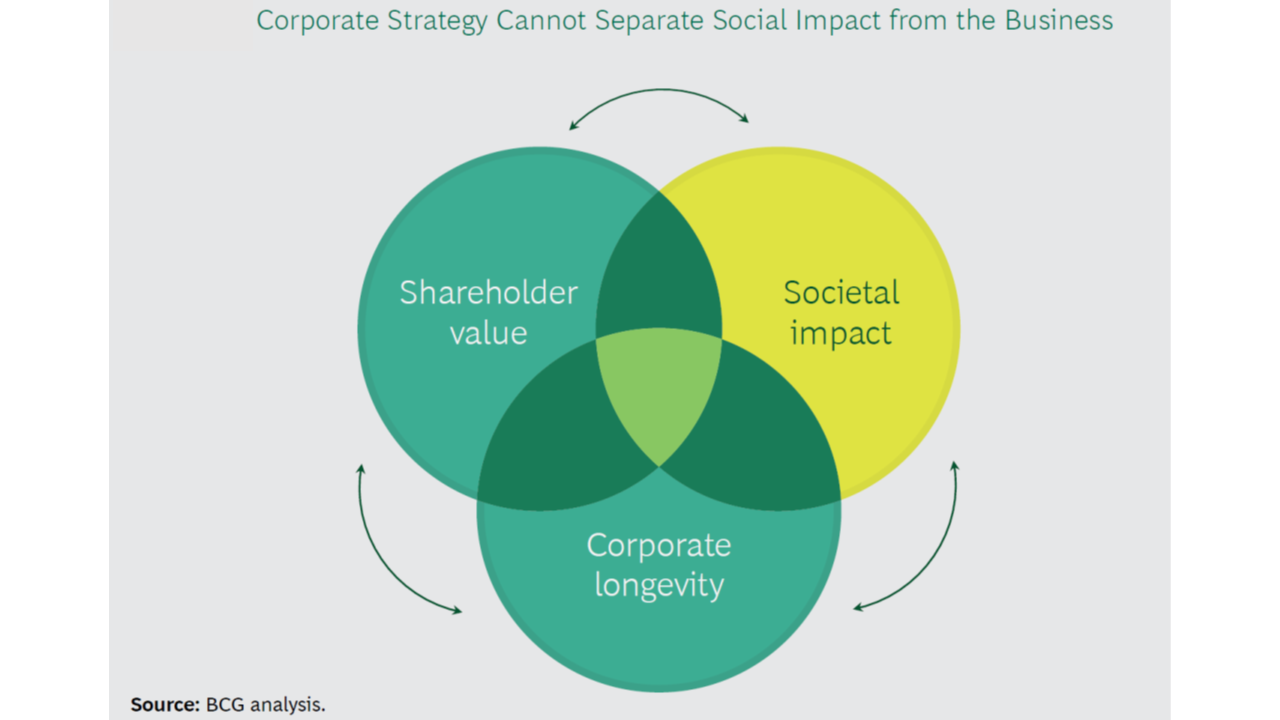

From a sustainability perspective, the alignment of the remuneration policy with the institution’s

long-term risk management framework and objectives, seems relevant. In addition, a number of studies concluded that, although it is difficult to prove that short-term strategies result in the destruction of long-term values, in some cases the short-term orientations of managers and investors become self-reinforcing. Therefore, incentives to shift the overall business strategy towards more long-term goals (e.g. promoting ‘patient capital’, increasing the long-term commitments of shareholders or tie managers’ remunerations to long-term performances through training and disclosure of long-term oriented metrics) are relevant in view of the long-term horizon of sustainability risks and opportunities.

The impact of the remuneration policies on the achievement of sound and effective long-term risk

management objectives may be especially relevant when it comes to the variable remuneration of

categories of staff whose professional activities have a material impact on the institution’s risk profile, taking into account their roles and responsibilities in relation to its sustainability strategy.

Among the currently existing practices across the EU, variable remuneration of employees of (re)insurance undertakings is based on performance and mostly on short-term basis – annual bonuses, or bonuses linked to the business strategy over 3-5 years. The performance of employees would therefore need to be aligned with the longer-term horizon of sustainability risks.

For example, long-term strategy goals such as reducing financed emissions in the investment portfolio or limiting losses in the underwriting of natural catastrophes can be aligned with the remuneration goals horizon, as for example through:

- Medium-to-short term remuneration incentives linked to achieving set targets in reducing CO2 emissions of investments or linked to reduction of losses through risk prevention initiatives for climate adaptation purposes.

- Longer-term incentives linked to payment with shares in the company, nudging the executive to take decisions in the long-term interest of the company.

Where the remuneration strategy of the undertaking refers to vague discretionary measures of progress such as ‘improving sustainability’ or ‘driving a robust ESG program’, these should be supported by specific goals or commitments and be measurable, meaningful, and auditable.