Our recent article presented EIOPA’s RTS proposal regarding the requirements of sustainability risk management with respect to ORSA, governance and key functions within the future, significantly broadened Solvency II framework.

This article will focus on materiality and financial assessment of sustainability risks as well as on proposed metrics, targets, and actions described by the RTS draft.

Materiality assessment

The definition of materiality under Solvency II and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) are aligned in their focus on the potential impact of information on decision-making.

- Under Solvency II, for public disclosure purposes, materiality means that if an issue is omitted or misstated, it could influence the decision-making or judgment of users of the information, including supervisory authorities. As to financial materiality, sustainability risks can translate in a financial impact on the (re)insurer’s assets and liabilities through existing risk categories, such as underwriting, market, counterparty default or operational risk as well as reputational risk or strategic risk. In other words, they are ‘drivers’ to existing risk categories.

- Similarly, the ESRS defines materiality as the potential for sustainability-related information to influence decisions that users make on the basis of the undertaking’s reporting. In the context of financial materiality, which is relevant for Solvency II purposes, the ESRS specifies that a sustainability matter is considered material if it could trigger or reasonably be expected to trigger material financial effects on the undertaking. This includes material influence on the undertaking’s development, financial position, financial performance, cash flows, access to finance or cost of capital over the short-, medium- or long-term. The materiality of risks is based on a combination of the likelihood of occurrence and the potential magnitude of the financial effects.

The two frameworks are aligned as material financial effects, as defined by the ESRS, would likely influence the decision-making or judgment of users of the information, including supervisory authorities. This alignment enables undertakings to apply a consistent materiality assessment approach across both Solvency II and ESRS reporting requirements.

Both Solvency II and ESRS do not set a quantitative threshold for defining materiality. The RTS do not specify a threshold for materiality either, considering this should be entity-specific. The undertakings should however define and document clear and quantifiable materiality thresholds, taking into account the above and provide an explanation on the assumptions made for the categorisation into non-material and on how the conclusion on the materiality has been reached. The classification of an exposure or risk as material has bearing on its prudential treatment, as it is a factor that determines whether the risk should be further subject to scenario analysis in the undertaking’s ORSA. The RTS require the undertaking to explain its materiality threshold in the plan: the assumptions for classifying risks as (non-) material in light of the undertaking’s risk appetite and strategy.

The materiality assessment should consider that:

- Sustainability risks are potential drivers of prudential risk on both sides of the (re)insurers’ balance sheet.

- Sustainability risks can lead to potential secondary effects or indirect impacts.

- The exposure of undertakings to sustainability risks can vary across regions, sectors, and lines of business.

- Sustainability risks can materialise well beyond the one-year time horizon as well as have sudden and immediate impact. Therefore, the materiality assessment necessitates a forwardlooking perspective, including short, medium, and long term. For example, certain geographical locations may not be subject to flood risk today but may be so in the future due to sea level rise. The risk assessment should be performed gross and net of reinsurance, to measure the risk of reliance on reinsurance.

The materiality assessment would consist of a high-level description of the business context of the undertaking considering sustainability risks (‘narrative’) and the assessment of the exposure of the business strategy and model to sustainability risk (‘exposure assessment’), to decide whether a risk could be potentially material. Following this, based on the identification of a potentially material risk, the undertaking would perform an assessment of the potential financial impact (i.e., financial risk assessment, as part of ORSA).

The narrative should describe the business context of the undertaking regarding sustainability risks, and the current strategy of the undertaking. It also describes the long-term outcome, the pathway to that outcome, and the related actions to achieve that outcome (e.g., emissions pathways, technology developments, policy changes and socio-economic impacts).

The narrative would include a view on the broader impact of national or European transition targets on the economy, or the effect of a transition risk throughout the value chain. The narrative should include other relevant sustainability risks than climate, such as risks related to loss of biodiversity, or social and governance risks, as well as interlinkages between sustainability risks (e.g., between climate and biodiversity or climate and social) and spill-over and compounding effects looking beyond specific sustainability risk drivers on particular lines of business.

Sustainability narratives, indicators, and interlinkages

- Narrative: For example, for climate change undertakings may refer to publicly available climate change pathways (i.e., the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS)) or develop their own climate change pathway.

- Indicators: Macro-prudential risk indicators or conduct indicators may provide additional insights and help the undertaking form its view on the future development of sustainability risks. Especially over a longer horizon, sustainability risk could have a wider and compounding impact on the economy and interactions between the financial and the real economy would need to be considered. For example, indirect impacts of climate change could lead to increase in food prices, migration, repricing of assets and rising social inequalities. All these indirect drivers will, in turn, impact the real economy as well as the financial sector, even more so as they could also trigger political instability. Macroprudential concerns could include, for example, plausible unfavourable forward-looking scenarios and risks related to the credit cycle and economic downturn, adverse investments behaviours or excessive exposure concentrations at the sectoral and/or country level. For example, EIOPA financial stability and conduct ESG risk indicators can be used to assess the external environment and business context in which climate change-related risks/opportunities can arise for the undertakings, the risk indicators will give an indication of macro-prudential risk in the insurance sector, and potential ESG related developments at sector level to the detriment of consumer protection.

- Interlinkages: For example, increasing temperatures leading to increased mortality risk affecting health business can potentially create underwriting as well as legal transition risk if the conditions for triggering a liability insurance have been met (e.g. a company failing to mitigate/adapt the risk). But also, a sharp increase in physical risks can lead to public policies focusing on a faster economy transition, leading in turn to higher transition risks. Physical and transition risks can impact economic activities, which in turn can impact the financial system. At the same time, the interconnectedness of the financial sector, and more generally of the economy, can create secondary effects: physical risk reducing the value of property, reducing in turn the value of collateral for lending purposes or increasing the cost of credit insurance, leading to economic slowdown; or physical damage caused by extreme weather events to critical infrastructure increasing the potential for operational/IT risks, amplifying supply chain disruption and disruption to global production of goods.

Based on the narrative, through qualitative and quantitative analyses, undertakings should arrive at an assessment of the materiality of their exposure to sustainability risks. A qualitative analysis could provide insight in the relevance of the main drivers in terms of traditional prudential risks. A quantitative analysis could assess the exposure of assets and underwriting portfolios to sustainability risk.

Exposure assessment

The aim is to identify sustainability risk drivers and their transmission channels to traditional prudential risks (i.e. market risk, counterparty risk, underwriting risk, operational risk, reputational risk and strategic

risk). Additionally, the assessment should provide insight into (direct) legal, reputational or operational risks or potential (indirect) market or underwriting risks, which could arise from investing in or underwriting activities with negative sustainability impacts, or from the undertaking misrepresenting its sustainability profile in public disclosure.

- Qualitative analysis to help identifying the main drivers of climate change risks:

- Transition risk drivers include changes in policies, technologies, and market preferences as well as the business activities of investees and commercial policyholders and policyholder preferences. At macro level, it may include consideration of failure of national governments to meet transition targets.

- Physical risk drivers include level of both acute and chronic physical events associated with different transition pathways and climate scenarios. This involves assessing the impact of physical risks to counterparties (investees, policyholders, reinsurers) as well the insurer’s own operations (e.g.to insurer’s business continuity, also for outsourced services). For climate change-related risks, the assessment should consider the evolution of extreme weather-related events for insurers underwriting natural catastrophe risks (incl. in property and health insurance).

- Geographical exposure: Identify potential exposure of assets or insured objects to sustainability risk based on, for example, the location of operations, assets or insured objects or supply chain dependencies of investee companies in geographical areas, regions or jurisdictions prone to (physical) climate, other environmental or social risks.

- Natural catastrophe and environmental risk datahubs such as the Copernicus datasets on land (use) or biodiversity can give an indication of relevant environmental risks across regions.

- Social risk indicators identify countries or regions that are vulnerable to social risk, measure social inequality or development. These can give an indication on potential social risk exposure of assets or liabilities located in those regions.

- Economic activity/sector-based exposure: Identify potential exposure of assets or lines of business or insured risks to potential sustainability risks based on the impact of the investee (or supply chain dependencies of the investee) or the policyholder’s economic activity, or their dependency on environmental or social factors. Such assessment should however not only focus on for example, exposures to climate related sectors, but also to other sectors which may be indirectly affected by (transition) risks.

- Alignment of the economic activity with the climate and environmental objectives and screening criteria set out in the Taxonomy Regulation and Climate, Environmental Delegated Regulations, as supported by the taxonomyrelated disclosures.

- Biodiversity loss, a high-level exposure assessment of could be carried out using the level of premiums written in economic sectors with a high dependence on ecosystem services and/or a high biodiversity footprint (economic exposure) and the probability of occurrence of the associated nature-related risk factors.

- Social risks, exposure of assets or liabilities to economic activities in ‘high risk social sectors’, can be identified by referring to the Business and Human Rights Navigator (UN Global Compact), which can help mapping exposure to sectors at high risk of relying on child labour, forced labour, or sectors negatively impacting on equal treatment (incl. restrictions to freedom of association) or on working conditions (inadequate occupational safety and health, living wage, working time, gender equality, heavy reliance on migrant workers) or have negative impacts on indigenous people.

Financial risk assessment

Where the exposure is deemed material, based on the thresholds set by the undertaking, a more detailed evaluation of the financial risks combining quantitative and/or qualitative approaches should inform the financial impact on the undertaking’s balance sheet. Here the assessment should aim to identify the key financial risk metrics and provide a view of the expected impact of such risks under different scenarios and time horizons at various levels of granularity.

Scenarios

When assessing the potential financial impact of material sustainability risks, the RTS sets out that undertakings should specify at a minimum two scenarios that reflect the materiality of the exposure and the size and complexity of the business. One of the scenarios should be based on the narrative

underpinning the materiality assessment. Where relevant, the scenarios should consider prolonged,

clustered, or repeated events, and reflect these in the overall strategy and business model including

potential stresses linked to the

- availability and pricing of reinsurance,

- dividend restrictions,

- premium increases/exclusions,

- new business restrictions,

- or redundancies.

For climate change risks, the Solvency II Directive requires undertakings with a material exposure to climate change risks to specify at least two long term climate change scenarios:

(a) a long-term climate change scenario where the global temperature increase remains below two degrees Celsius;

(b) a longterm climate change scenario where the global temperature increase is significantly higher than two degrees Celsius.

Experience to date shows that the most used scenarios are those designed by NGFS43, IPCC Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) or tailor-made scenarios (set by regulators, e.g. for nature-related scenarios or for stress testing purposes.

Time horizons

The time horizon should ensure that the time horizon for analysing sustainability risks is consistent with the undertaking’s long-term commitments. The time horizon should allow to capture risks which may affect the business planning over a short-to-medium term and the strategic planning over a longer term.

The time horizon chosen for the materiality assessment in sustainability risk plan should also enable the integration of the risk assessment process with time horizons applied for the purposes of the ORSA for risk assessment purposes.

Taking the example of the impact of climate change: its impact can materialise over a longer time horizon than the typical 3-5 years (re)insurers’ strategic and business planning time horizons considered in the ORSA. It is argued that ORSA time horizons are too short to integrate the results of such longer-term climate change scenarios. Nevertheless, the ORSA should allow for the monitoring of the materialisation of risks over a longer term. At the same time, climate change-related risks and opportunities can affect the business planning over a short term and the strategic planning over a longer term.

The RTS specify the time horizons for sustainability risk assessment, to promote supervisory convergence and increase the consistency of risk assessment across undertakings and with decisionmaking. For this purpose, the RTS stipulates that the following time horizons for the sustainability risk assessment apply:

- Short term projection: 1-5 years

- Medium term projection: 5-15 years

- Long term projection: min. 15 years

Documentation and data requirements

The sustainability risk assessment should be properly documented. This would include documenting the methodologies, tools, uncertainties, assumptions, and thresholds used, inputs and factors considered, and main results and conclusions reached.

Undertakings’ internal procedures should provide for the implementation of sound systems to collect and aggregate sustainability risks-related data across the institution as part of the overall data governance and IT infrastructure, including to assess and improve sustainability data quality.

Undertakings would need to build on available sustainability data, including by regularly reviewing and

making use of sustainability information disclosed by their counterparties, in particular in accordance with the CSRD or made available by public bodies.

Additional data can be sourced from interaction with investees and policyholders at the time of the

investment or underwriting of the risk, or estimates obtained from own analysis and external sources.

Undertakings should, where data from counterparties and public sources is not available or has shortcomings for risk management needs, assess these gaps and their potential impacts. Undertakings

should document remediating actions, including at least the following: using estimates or (sectoral) proxies as an intermediate step – the use of such estimates should be clearly indicated – , and seeking to reduce their use over time as sustainability data availability and quality improve; or assessing the need to use services of third-party providers to gain access to sustainability data, while ensuring sufficient understanding of the sources, data and methodologies used by data providers and performing regular quality assurance.

Frequency

The RTS aim to align the frequency of performance of the materiality and financial risk assessments

with, on the one hand, the cycle of the submission of the regular supervisory report to the supervisor ‘at least every three years’, if not stipulated differently by the supervisor, and the requirement for undertakings to assess material risks as part of their ORSA ‘regularly and without any delay following any significant change in their risk profile’.

Significant changes to the undertaking’s risk profile can include material change to its business environment including in relation to sustainability factors, such as significant new public policies or shifts in the institution’s business model, portfolios, and operations.

In addition, for the frequency of the financial risk assessment, the RTS need to consider that undertakings (except for SNCUs) are required to conduct at regular intervals, at a minimum every three years, the analysis of the impact of at least two long-term climate change scenarios for material climate change risks on the undertaking’s business.

Based on these considerations, the RTS set out that the materiality and financial risk assessment should be conducted at least every three years, and regularly and without any delay following any significant change in their risk profile.

Building on the requirements , the RTS specifies that key metrics and the results of the sustainability risk

plan should be disclosed at least every year or, for smaller and non-complex undertakings, at least every two years or more frequently in case of a material change to their business environment in relation to sustainability factors.

Metrics

Prescribing a list of metrics in sustainability risk plans can help

- in promoting risk assessment,

- improve comparability of risks across undertakings,

- promote supervisory convergence in the monitoring of the risks and

- enable relevant disclosures.

At the same time, it is important to allow undertakings flexibility in defining their metrics to avoid missing useful undertaking-specific information. Therefore, the RTS describes the key characteristics of the metrics and provides a minimum list of relevant metrics to compute.

Backward-looking (current view) and forward-looking, can be tailored to the undertaking’s business model and complexity, while following key characteristics apply. Metrics should

- provide a fair representation of the undertakings’ risks and financial position using the most up-to-date information.

- be appropriate for the identification, measurement, and monitoring of the actions to achieve the risk management targets.

- be calculated with sufficient granularity (absolute and relative) to evaluate eventual concentration issues per relevant business lines, geographies, economic sectors, activities, and products to quantify and reflect the nature, scale, and complexity of specific risks.

- allow supervisors to compare and benchmark exposure and risks of different undertakings over different time horizons.

- be documented to a sufficient level to provide relevant and reliable information to the undertaking’s management and at the same time be used as part of supervisory reporting and, where relevant for public disclosure, ensuring sufficient transparency on the data (e.g. source, limitations, proxies, assumptions) and methodology (e.g. scope, formula) used.

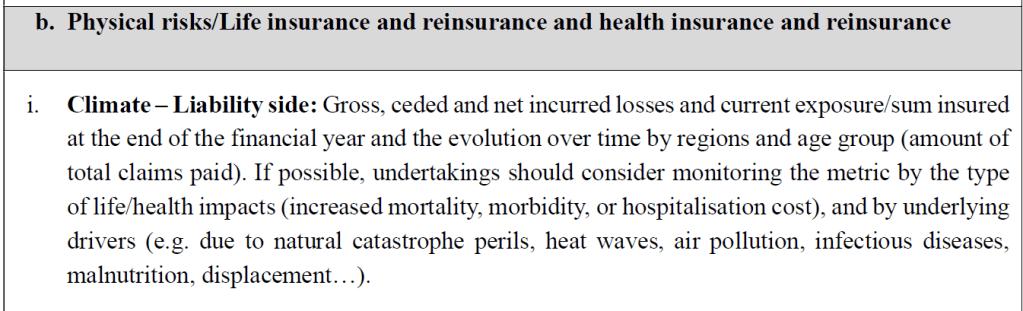

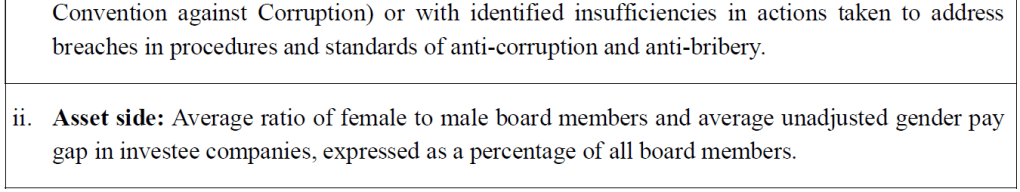

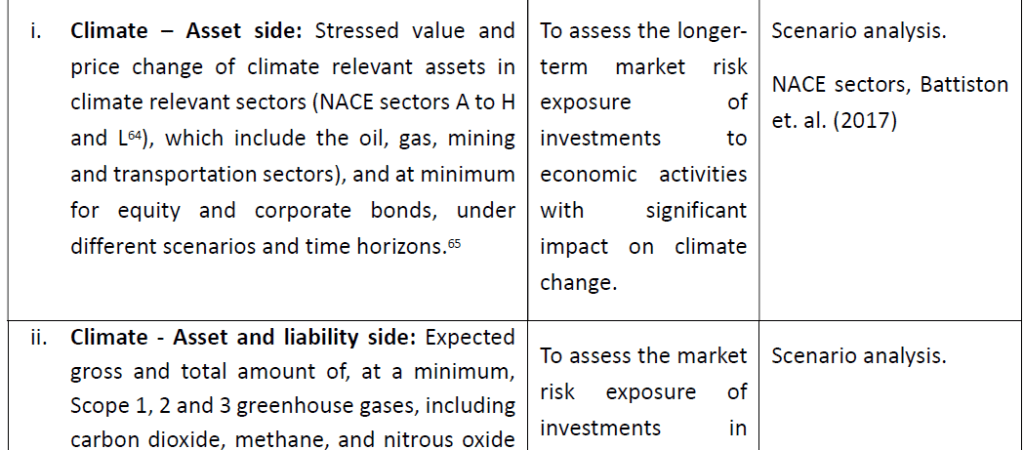

The RTS requires the following minimum current view metrics:

The following list includes optional metrics which could be considered by the undertaking on a voluntary basis to report on the results of scenarios analysis (financial risk assessment) for material sustainability risks.

Targets

Based on the results of the sustainability risk assessment, the undertaking’s risk appetite and long-term

strategy, the undertaking should set quantifiable targets to reduce or manage material sustainabilityrelated exposure/risks or limits sustainability-related exposure/risks to monitoring prudential risks over the short, medium, and long term.

The undertaking should, based on its risk appetite, specify the type and extent of the material sustainability risks the undertaking is willing to assume in relation to all relevant lines of business, geographies, economic sectors, activities and products (considering its concentration and diversification objectives) and set its risk management targets accordingly.

Undertakings shall explain the way the target will be achieved or what is their approach to achieve the

target. Intermediate targets or milestones should allow for the monitoring of progress of the undertaking in addressing the risks. The undertakings should specify the percentage of portfolio covered by targets.

The targets should be consistent with any (transition) targets used in the undertaking’s transition plans and disclosed where applicable. The targets and measures to address the sustainability risks will consider the latest reports and measures prescribed by the European Scientific Advisory Board on climate change, in particular in relation to the achievement of the climate targets of the Union.

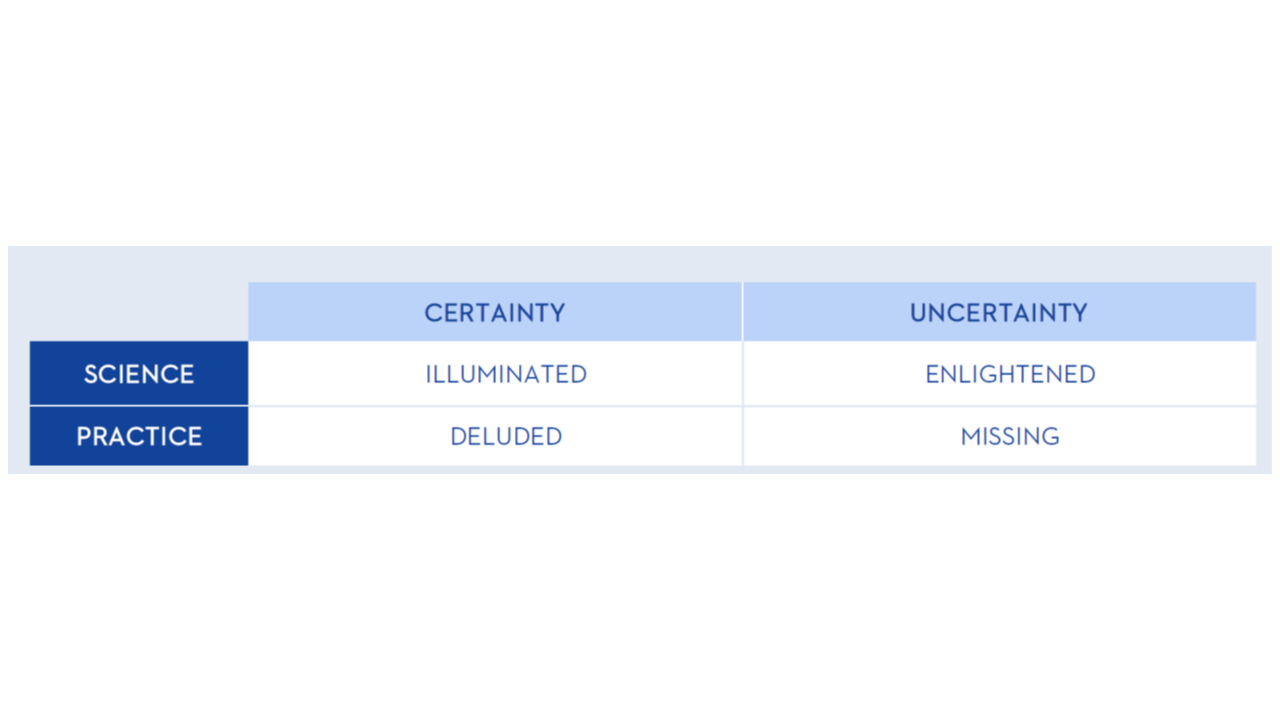

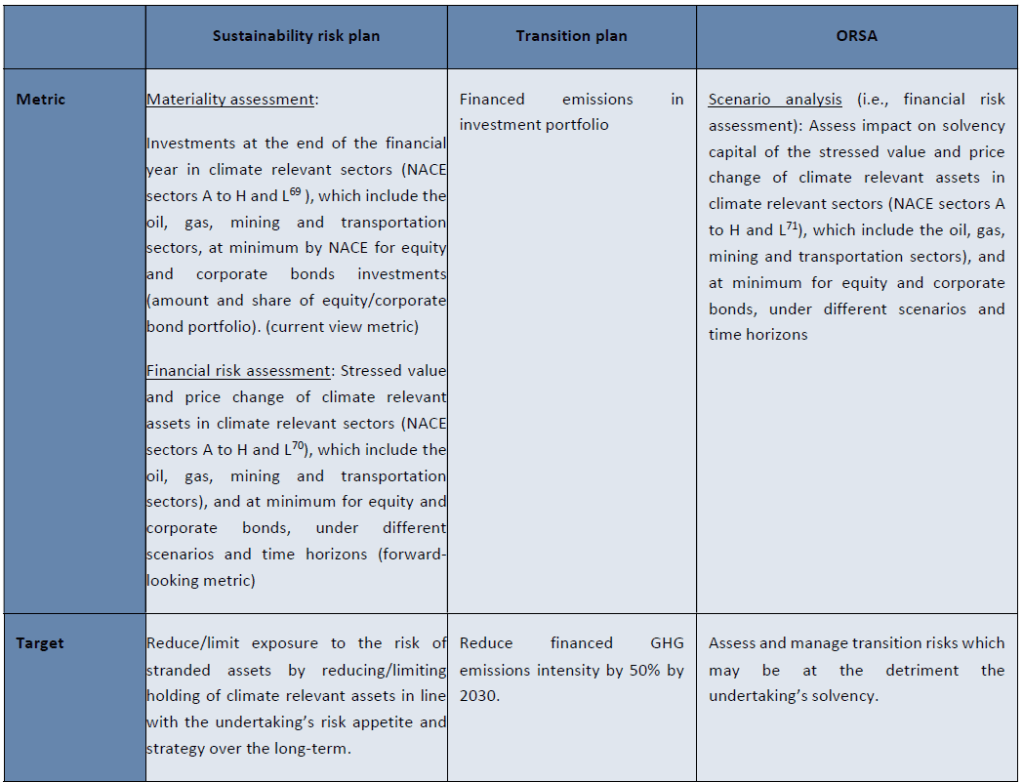

Relation between targets, metrics, and actions across transition plans, sustainability risk plans and ORSA, applied to an example for transition risk assessment for climate risk-related investments

Actions

Actions to manage risks should be risk-based and entity-specific.

- Actions set out in undertakings’ transition plans, for example under CSDDD can inform the sustainability (transition) risk to the undertaking’s business, investment, and underwriting. Such transition plan actions typically involve:

- Limiting investment in non-sustainable activities/companies Introduction of sustainability criteria in the investment decision.

- Re-pricing of risks.

- Integrating sustainability into the investment guidelines.

- Stewardship, impact investing, impact underwriting.

- Integrating ESG into the underwriting standards and guidelines of the undertaking.

- Product development considering the impact on climate change.

The measures in the transition plan and actions to address financial risks arising from the transition need to be integrated into the investment, underwriting and business strategy of the undertaking. They need to be measurable and where actions fail to meet their expressed target, these should be monitored and, where necessary, adjusted.