EIOPA / ECB December 2024

Executive Summary

Increased economic exposure and the growing frequency and severity of natural catastrophes linked to climate change have been driving up the cost of natural catastrophes in Europe. Between 1981 and 2023, natural catastrophes caused around €900 billion in direct economic losses within the EU, with one-fifth of these losses having occurred in the last three years alone. However, over the same period, only about a quarter of the losses incurred from extreme weather and climate-related events in the EU were insured – and this share is declining.

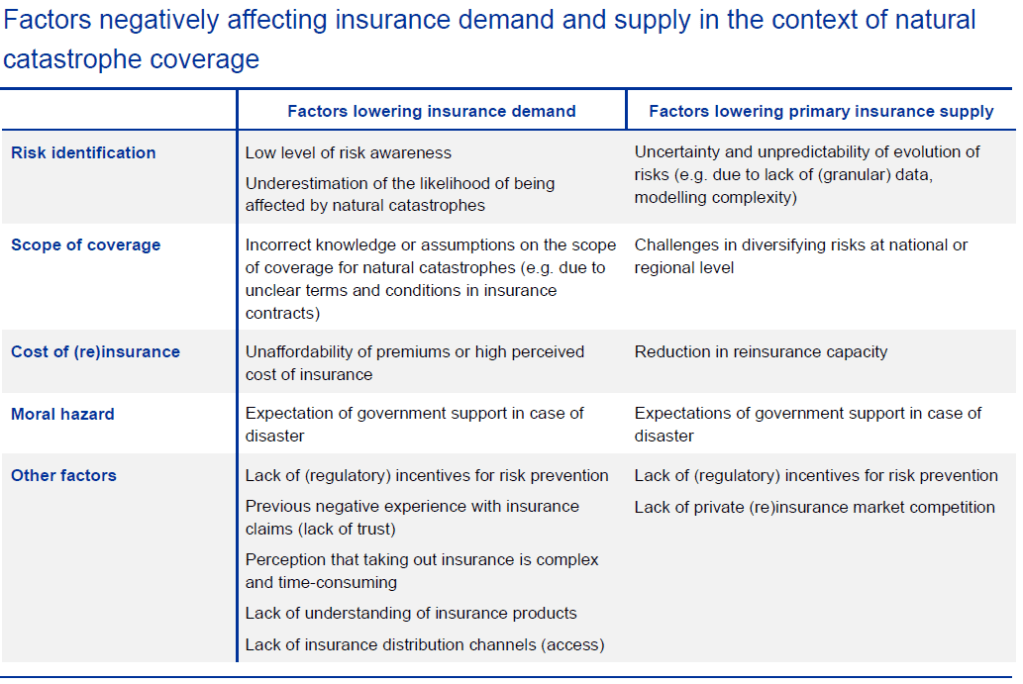

This “insurance protection gap” is expected to widen further due to the increasing risk posed by climate change. Europe is the fastest-warming continent in the world and increasing climate risk is likely to have implications for both the supply of and demand for insurance if no relevant measures are in place. As the frequency and severity of climate-related events grow, (re)insurance premiums are expected to rise. This will make insurance less affordable, particularly for low-income households. Climate change also increases the unpredictability of these events, which may prompt insurers to stop offering catastrophe insurance in high-risk areas. At the same time, low risk awareness and reliance on government disaster aid further dampen insurance uptake by households and firms.

Recent events, such as the 2024 flooding in central and eastern Europe and in Spain, have further illustrated the challenges that extreme weather events can pose for the EU and its Member States. These events highlight the importance of emergency preparedness, risk mitigation, and adaptation efforts to prevent and/or minimise the losses from natural disasters, as well as the relevance of national insurance schemes in reducing the economic impact of natural catastrophes. They also bring to the fore the importance of addressing the insurance protection gap and the associated burden on public finances.

National schemes aim to broaden insurance coverage and encourage risk prevention. Typically, they do so by setting up risk-based (re)insurance structures involving public-private sector coordination for multiple perils (e.g. floods, drought, fires and windstorms). Some of the schemes further support the availability of insurance through mandatory insurance coverage and improve the affordability of insurance through national solidarity mechanisms. At the same time, there are fewer risk diversification opportunities at national than at EU level and reliance on both national and EU public sector outlays has been growing. Therefore, it is beneficial to discuss at EU level how adaptation measures can help in proactively reducing disaster losses and how the sharing of losses between the public and private sectors can help in raising risk awareness and improving risk management before disasters occur.

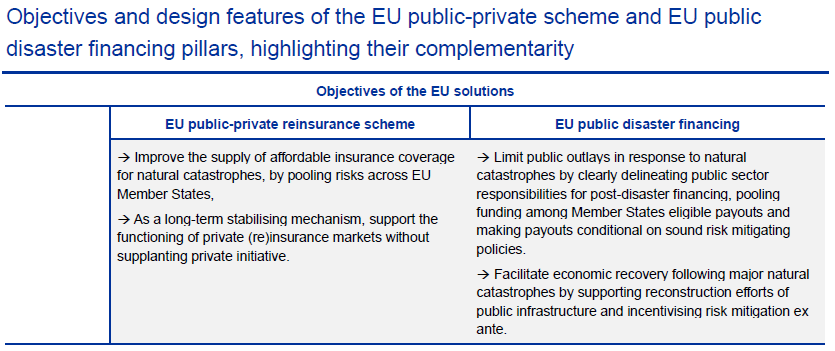

Building on existing national and EU structures, the EIOPA and BCE spell out a possible EU-level solution composed of two pillars, firmly anchored in a multi-layered approach:

- An EU public private reinsurance scheme: this first pillar would aim to increase the insurance coverage for natural catastrophe risk where insurance coverage is low . The scheme would pool private risks across the EU and across perils, with the aim of further increasing diversification benefits at EU level, while incentivising and safeguarding solutions at national level. It could bef unded by risk based premiums from (re)insurers or national schemes , while taking into account potential implications of risk based pricing for market segmentation . Access to the scheme would be voluntary. The scheme would act as a stabilising mechanism over time to achieve economies of scale and diversification for the coverage of high risks at the EU level, similar to an EU public private partnership.

- An EU fund for public disaster financing: this second pillar would aim at improving public disaster risk management among Member States . Payouts from the fund would target reconstruction efforts following high loss natural disasters, subject to prudent risk mitigation policies, including risk adaptation and climate change mitigation measures. The EU fund would be financed by Member State contributions adjusted to reflect their respective risk profiles. Fund payouts would be condition al on the implementation of concrete risk mitigation measures preagreed under national adaptation and resilience plans. This would incentivise more ambitious risk mitigation at Member State level before and after disasters. Membership would be mandatory for all EU Member States.

Rising economic losses and climate change

Economic losses from extreme weather and climate events are increasing and are expected to rise further due to the growing frequency and severity of catastrophes caused by global warming. Between 1981 and 2023, natural catastrophe-related extreme events caused around €900 billion in direct economic losses in the EU, with more than a fifth of the losses occurring in the last three years (2021: €65 billion; 2022: €57 billion; 2023: €45 billion).

Europe is the fastest-warming continent in the world and the number of climate-related catastrophe events in the EU has been rising, hitting a new record in 2023. Moreover, climate change is already now affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe and its adverse impacts will continue to intensify. In the EU, all Member States face a certain degree of natural catastrophe risk and the welfare losses are estimated to increase in the absence of relevant measures to improve risk awareness, insurance coverage and adaptation to the rising risks.

Over the last ten years, the reinsurance premiums for property losses stemming from catastrophes have increased across all major insurance markets. In Europe, property catastrophe reinsurance rates have risen by around 75% since 2017. While there may be various factors affecting reinsurance prices, the increasing frequency and severity of events is likely to trigger further repricing of reinsurance contracts, which can in turn increase prices offered by primary insurers. The rising risks may even prompt insurers to retreat from certain areas or types of risk coverage. Moreover, since insurance policies are typically written for one year only, such repricing or insurance retreat may be abrupt. Reduced insurance offer is justified where risks become excessively high or unpredictable. In particular, insurance cannot palliate for inadequate climate adaptation, spatial planning and (re)building conventions.

At the same time, take-up of natural catastrophe insurance in the EU is declining among low-income households, thus increasing the pressure on governments to provide support in the event of a natural catastrophe. For instance, the share of low-income consumers with insurance for property damage caused by natural catastrophes has declined from around 14% to 8% since 2022. Affordability and budgetary constraints are the main reason why 19% of European consumers do not buy or renew insurance. Low-income households may also be disproportionately vulnerable to financial stress and are more likely to live in areas with increased exposure to environmental stress or natural catastrophes, due to the affordability of land and housing or limited resources to relocate to safer areas or invest in disaster-resistant housing. Insurance affordability stress might eventually also contribute to housing affordability issues, because if a larger portion of income is spent on insurance, a smaller portion is available for other expenses (e.g. rent). Therefore, solutions should consider vulnerability and consumer protection aspects.

Lessons from national insurance schemes

National schemes to supplement private insurance cover for natural catastrophes, such as PPPs, help improve insurance coverage and reduce the insurance protection gap. Looking at the European Economic Area (EEA), the share of insured losses tends to be higher in countries with such national schemes: the average share across countries with a national scheme is around 47%, while it is below 18% for those without a national scheme. Currently, eight EEA Member States have established a national scheme:

The schemes share the same objective: they all aim to enhance societal resilience against disasters. They typically do so by improving risk awareness and prevention, while increasing insurance capacity through more affordable (re)insurance.

While the design features vary by scheme, some of them are recurring:

- Scope: most national insurance schemes have a broad scope of coverage, which allows them to pool risks across multiple perils and assets. The majority also incorporate a mandatory element, requiring either mandatory offer or mandatory take up of insurance by law .

- Structure: the prevalent structure of national schemes is that of a public (re)insurance scheme. Most schemes offer complementary direct (re)insurance and are of a permanent nature.

- Payouts and premiums: national schemes are typically indemnity based (i.e. payouts are based on actual losses rather than quantitative/parametric catastrophe thresholds). Premiums are mostly risk based.

- Risk transfer and financing: the use of reinsurance by the schemes depends on the availabil ity and the cost of reinsurance, with national schemes increasingly facing issues over affordability. Public financing of the scheme is not an essential design feature.

- Risk mitigation and adaptation measures: initiatives to ensure proper coordination between the public and private sectors on risk identification and prevention are now emerging in response to climate change. Private and public sector responsibilities are typically divided, with the private market contributing its insurance expertise and modelling capacity, while the public sector provides the legal basis and operating conditions.

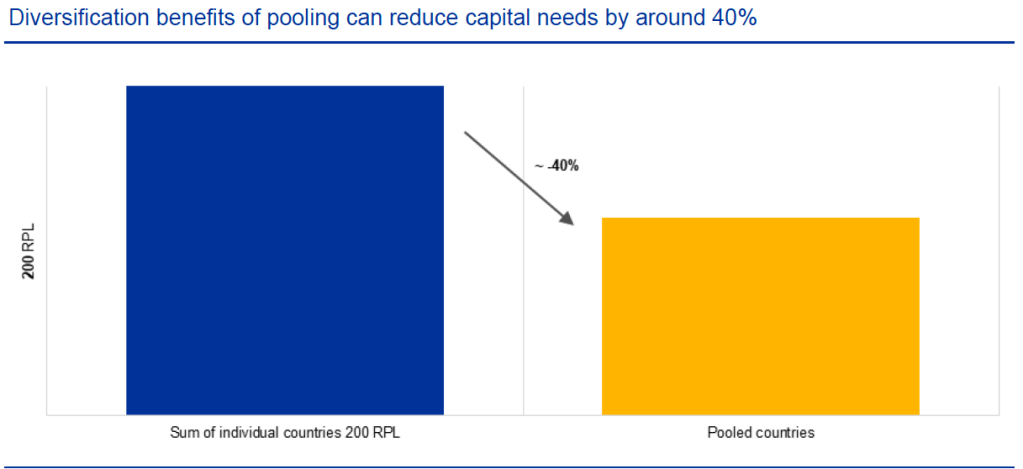

Lesson 1: an EU solution could cover a wider range of perils and assets across several Member States, thus allowing for greater risk pooling and risk diversification benefits than at a national level. This can be particularly relevant for small countries where a single catastrophe can affect the whole country and for countries without a national insurance scheme. By pooling catastrophe risk across different exposures, regions and uncorrelated perils within a single EU scheme, it may be possible to reap larger risk diversification benefits than could be achieved at national level. This would, in turn, reduce the required capital needed to back the risks and lower the cost of reinsuring them. Mandatory elements to boost the demand for or offer of insurance could further increase the risk diversification benefits and limit adverse selection. However, this would also require a certain degree of harmonisation of existing national practices.

Lesson 2: an EU-wide solution could include a permanent public-private reinsurance scheme to complement private sector or national initiatives. Setting up a public-private reinsurance scheme, as opposed to a private structure, would have the advantage that it could be accessed by a large range of entities: primary insurers, reinsurers and various national schemes. Therefore, such a scheme would require no harmonisation of existing national practices. Participation in such a scheme would be voluntary, so that the scheme supplements, rather than crowds out, private sector or national initiatives. Making the scheme permanent would allow for pooling risk over time, thus reaping even greater diversification benefits than if risks were pooled only across perils, asset types and Member States.

Lesson 3: an EU-wide solution could further support affordable risk-based premium setting, owing to the potentially sizeable risk diversification benefits that could be achieved across Member States. Given the significant heterogeneity in the risks faced by policyholders across Member States, flat premiums or premiums capped by law could imply a relatively high level of cross-subsidisation and solidarity, which might be difficult to agree upon at EU level. A risk-based approach at EU level could support additional risk diversification benefits achieved from risk pooling across Member States, time horizons, perils and asset types.

Lesson 4: since public funding mechanisms for disaster recovery are stretched and reinsurance prices have been rising, an EU solution could aim to finance itself through risk-based premiums and could explore tapping capital markets. In addition to collecting risk-based premiums (see Lesson 3), the scheme could explore tapping the capital markets by issuing catastrophe bonds or other insurance-linked securities. The catastrophe bonds could be indemnity-based or parametric (or both), depending on the further design features of the solution (e.g. whether it would provide indemnity-based or index-based payouts). The extensive risk pooling enabled by the EU solution could also allow for the issuance of catastrophe bonds that could be less risky and more transparent than many other catastrophe bonds, thus attracting a relatively wide set of investors. Ultimately, the EU solution could in principle be set up with no public financing or backstop.

Lesson 5: an EU solution could support both insurance and public sector initiatives geared towards risk mitigation and adaptation as part of a public-private concerted action. For instance, an EU solution could improve the availability, quality and comparability of data on insured losses across EU countries. It could also support the modelling of risk prevention and the integration of climate scenario analysis into estimates of future losses (both insured and uninsured) from natural disasters. The analysis of EU solutions might further promote the use and development of open-source tools, models and data to enhance the assessment of risks. In this context, care should be taken to prevent further market segmentation or demutualisation based on granular risk analysis, which could widen the insurance protection gap in the medium term.

A possible EU approach

An EU-level system could rest on two pillars, building on existing national and EU structures:

- Pillar 1: EU public private reinsurance scheme. Establishing an EU public private reinsurance scheme would serve to increase the insurance coverage for natural catastrophe risk. The scheme would pool private risks across the EU, perils and over time to achieve economies of scale and diversification at the EU level.

- Pillar 2: EU public disaster financing. The second pillar would look to improve public disaster risk management in Member States through EU contributions to public reconstruction efforts following natural disasters, subject to prudent risk mitigation policies, including adaptation and climate change mitigation measures

The EU public-private reinsurance scheme could help to provide households and businesses with affordable insurance protection against natural catastrophe risks, while also providing incentives for risk prevention. Embedded in the ladder of intervention, the design features of the scheme build on the five lessons learned from the analysis of the national schemes. The scheme seeks to (i) ensure coverage of a broad range of natural catastrophe risks, (ii) fulfil a complementary role to national and private market solutions, (iii) rely on risk-based pricing, (iv) reduce dependence on public financing in the long term, and (v) support concerted action on risk mitigation and adaptation.

The EU reinsurance scheme could seek to transfer part of the risks to capital markets via instruments such as catastrophe bonds. The market for these products is less developed in the EU than in North America. Part of the reason is the smaller scale of the issuances. The EU scheme could explore the feasibility of a pan-European catastrophe bond covering more perils than the bonds currently issued. This would serve the dual purpose of expanding the catastrophe bond market and bringing more niche risks directly to capital markets investors. The investors, in return, could benefit from the additional diversification offered by exposure to these risks relative to the risks currently covered.

Risk pooling is a fundamental concept in insurance, grounded in the law of large numbers. As independent risks are added to an insurer’s portfolio, the results become less volatile. For example, in a pool of insured vehicles, the actual number of accidents each year converges with the expected number as the size of the pool increases. In terms of capital, reduced volatility means lower capital needs and costs for the same level of protection. More diversified insurers can therefore offer cover at a lower price and given the level of capital, provide a higher level of protection.

The underlying risk (annual expected loss) remains unchanged when pooling risks together. However, the cost of covering or transferring the risk (cost of capital), along with the cost of information and operating costs, decreases with diversification and risk pooling. Operational costs are lower due to economies of scale, as they are shared among all participants in the pool. The cost of information is also lower , as the time and money required to obtain information can be shared among participants.

Solvency II requires insurers to hold sufficient capital to withstand a loss occurring with a

probability of 1 in 200 years. In an example, using the Moody’s RMS Europe NatCat Climate HD

model, and based on the current insured landscape, the pooled portfolio shows a reduction of

around 40% in the 1 in 200 year return period losses (RPL) compared to the sum of individual

values for countries. This reduction might be even larger if penetration of flood insurance increases. A similar analysis conducted by the World Bank, provid ing a framework for estimating the impact of pooling risks on policyholder premiums , supports these conclusions.

The EU disaster financing component would provide a complementary mechanism that governments could tap when managing natural catastrophe losses. Natural catastrophes can lead to significant costs for governments, including damage to key public infrastructure. The EU disaster financing component would help governments to manage a share of these expenses following a major disaster, thus supplementing their national budgetary expenditure. The component would cover damages caused to key public infrastructure that is inefficient or too costly to insure privately, with a view to supporting resilient reconstruction efforts and public space adaptation. Clear rules on contributions and conditions on the disbursement of the funds should encourage ex ante risk prevention by governments, to minimise the emergency relief and residual private risks that the government may need to cover following a major event.